New Delhi: Summers in India are not only increasing in intensity but are also arriving sooner. Early-season heatwaves across north and central India are the new normal.

D.S. Pai, head of Climate Research & Services at the India Meteorological Department (IMD) in Pune, told ThePrint that a lot of factors are at play here. “Intense urbanisation, reducing green cover and global climatic factors. It is getting worse every year, barring a few exception year.”

In April this year, maximum temperatures in Delhi climbed above 40 degrees Celsius on three days—between April 7 and 9, shows IMD data. It’s becoming a persistent and almost predictable refrain. On three occasions, since 2011, April temperatures have crossed this mark—2016, 2017 and 2022.

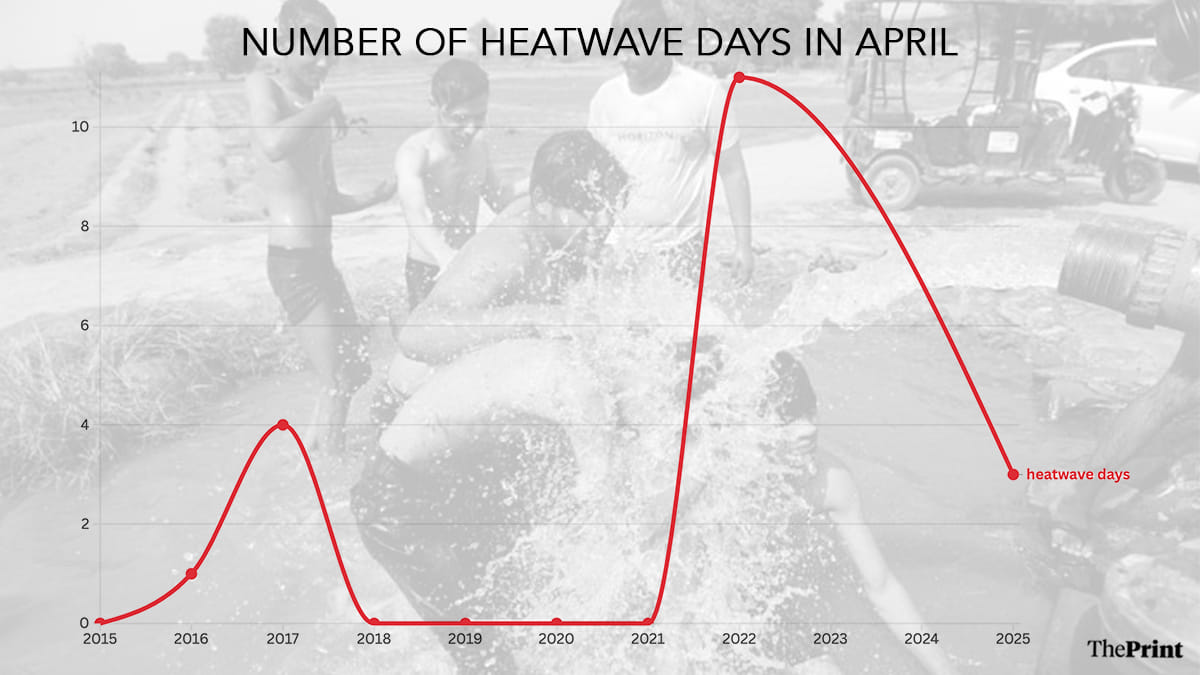

In 2016, on 17 April, daytime temperature in Delhi’s representative observatory, Safdarjung, touched 42 degrees Celsius, categorised as a heatwave day. The following year, in 2017, four heatwave days were recorded.

IMD’s data shows that in 2022, India recorded an abnormally warm April, with 11 heatwave days. This year, the national capital has recorded three heatwave days in April.

This is not just leading to a prolonged summer season, but is also eating into the spring season—February and March—which were historically transitional months between winter and summer.

“In the coming years, the key would be to adapt. We will need to make our cities and our infrastructure more climate resilient. Citizens will also need to be educated and trained to respond efficiently during such periods because intense heatwaves will impact employment, agriculture, public movement and healthcare—basically every aspect of our lives,” Pai said.

‘More intense summers’

IMD doesn’t announce the onset of summer, as it does for the southwest monsoon, heatwave conditions are assessed daily. But according to IMD assessments, apart from the traditionally impacted pockets of northwest and central India—Rajasthan, Delhi, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh—higher than normal temperatures are now being reported even in parts of northeast and southern India.

It defines heatwave as the period when the maximum temperature is above 40 degrees Celsius in the plains and at least 30 degrees Celsius in the hills. If its departure from the normal temperature in the region is between 4.5 and 6.4 degrees Celsius, it is categorised as a heatwave day, and if the temperature departure exceeds 6.4 degrees, it is considered a severe heatwave day.

Dr Mrutyunjay Mohapatra, director general of meteorology at IMD, explained that many local and global factors play a role in how intense the summer season will be each year. “But over the last few years, the trends are largely pointing toward more intense summers,” he told ThePrint.

Shoulder seasons

Warmer days are not limited to April. Above normal temperatures are spreading their tentacles into February and March.

This year, maximum temperatures were hovering near the 40-degree Celsius mark for nearly a week at the end of March. On 26 March, the maximum temperature in Delhi soared to a sweltering 40.5 degrees Celsius, which was around seven degrees above what is considered normal for this time of the year.

Climate scientists who have been observing temperature recordings in different parts of India said that 40 degrees Celsius is usually observed around the end of April or the first week of May.

The arrival of warm days and nights has been particularly early this time.

On 25 February, parts of Goa and Maharashtra recorded the first heatwave of the year. According to IMD records, it was also the first time a heatwave was recorded in the winter (January and February).

This year, Odisha and Jharkhand also experienced the earliest heatwaves in at least the last four years.

In their monthly analysis released at the end of each month, Met officials confirmed that the February of 2025 was the hottest February in 125 years.

Mahesh Palawat, vice president, meteorology and climate change, at Skymet Weather—a private weather service—explained that decadal variations in seasonal heat patterns are normal, but early onset of summers, with intense temperature recordings, have become the new normal in Indian cities.

“Of course, climate change is one of the factors behind such extreme temperatures. In fact, we have also been noticing that certain pockets within a city are experiencing higher recordings because of extreme urbanisation,” Palawat said.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Election fever & extreme heat alert—state govts yet to learn from Kharghar deaths