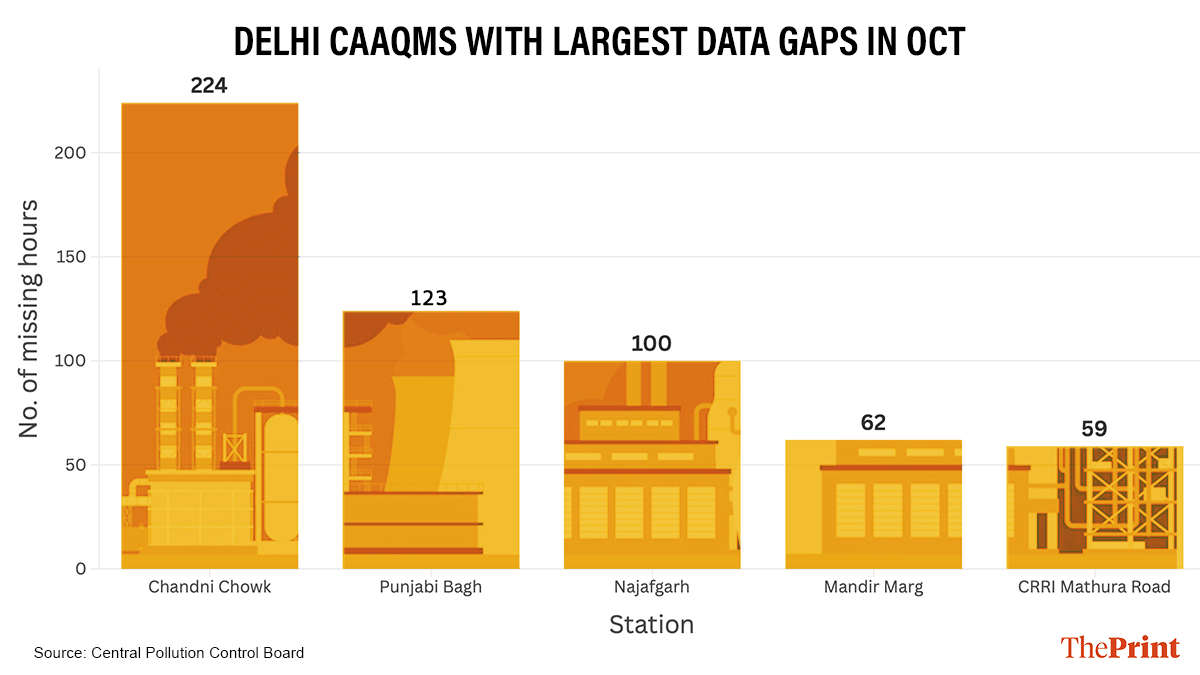

New Delhi: 224 at Chandni Chowk. 123 at Punjabi Bagh. And 100 at Najafgarh.

These were the number of hours that data on particulate matter 2.5, a toxic pollutant, was missing at air quality monitoring stations over the month of October.

ThePrint’s analysis of data available online by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) showed that missing air quality data wasn’t just a Diwali night anomaly, even though it was substantially worse then.

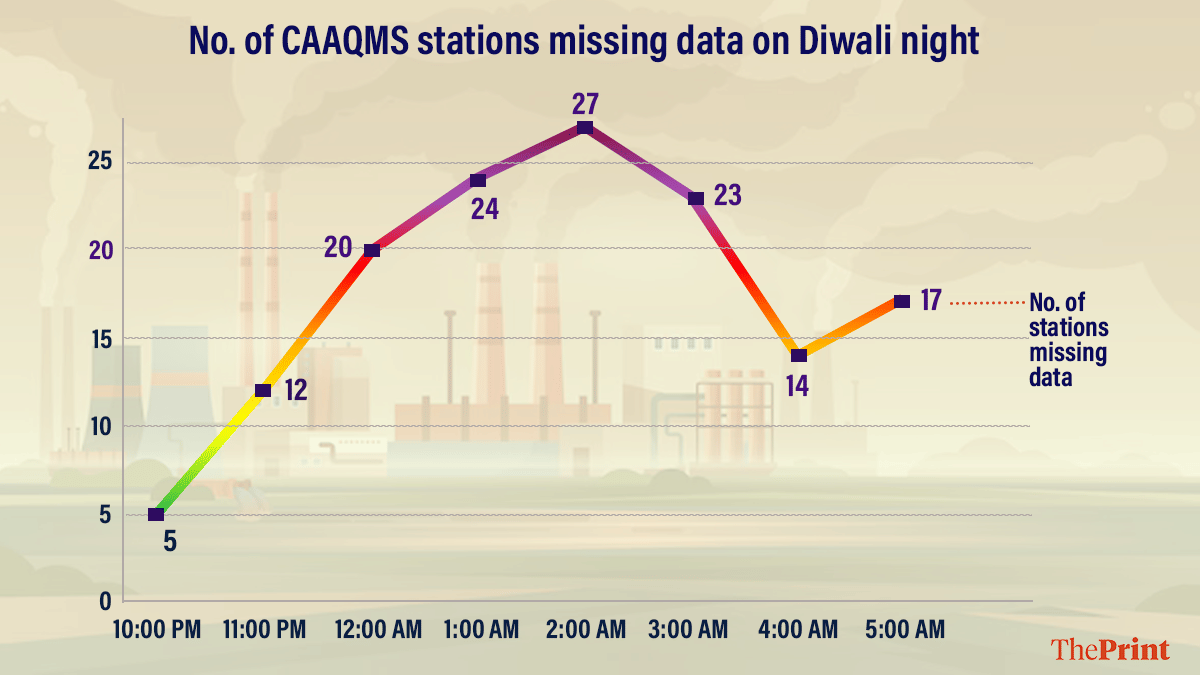

After midnight on Diwali, on 21 October, 28 out of 39 pollution monitors across the capital went blank. It was the first Diwali to be celebrated in Delhi with ‘green firecrackers’ in four years, after the Supreme Court lifted a blanket ban that was effected in 2021.

A closer look at air quality data over the entire month showed that none of the stations in Delhi continuously tracked PM2.5 levels.

Anand Vihar and Wazirpur had gathered the most, with just four to seven hours of missing PM2.5 data over 744 hours of October.

At stations in Okhla and Dwarka, data was not available for 40-46 hours.

At 224 hours, equivalent to nine days and eight hours, the worst PM2.5 data blackout was at Chandni Chowk station. It was followed by Punjabi Bagh and Najafgarh, data gaps at both of which scaled the three-digit mark.

Experts said large data gaps were worrying.

“If data is missing only for a few hours in a month, it could be a small calibration issue or a glitch. But if it’s missing for many days in a month, it means there’s a fundamental issue with the sensor, and it needs to be audited and upgraded,” said Sunil Dahiya, founder and lead analyst at think-tank Envirocatalysts.

Called Continuous Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Stations (CAAQMs), these monitors gather data without any manual intervention throughout the day, but they are maintained by different agencies.

The Chandni Chowk one, for instance, is managed by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), and the stations at Punjabi Bagh and Najafgarh stations are under the Delhi Pollution Control Board (DPCC).

“These CAAQMS systems are highly sophisticated equipment and need to be maintained well at all times, and not just in winter. Especially on crucial nights like Diwali, when all national and international eyes are on you, even one hour of failure should not be acceptable,” said Mohan George, consultant (clean air) at the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE).

Delhi’s environment minister Manjinder Singh Sirsa on Friday denied that any data was missing. “I have checked with DPCC and there’s no data missing from any of their stations or their records. May be, there could be a 10-15 minute lapse because of internet issues, but no data is missing. It could be that there’s an issue in uploading data or maintaining it, but from our end, the sensors are working and DPCC is collecting all necessary data.”

Officials of CPCB, which collates and maintains data from all monitoring stations, did not respond to multiple requests for comment till Friday night.

Also Read: Pollution does not appear to be an emergency for Indian govt, writes global media amid Diwali smog

Why it matters

Delhi consistently ranks among the world’s most polluted cities, and air quality deteriorates sharply each winter due to a combination of vehicular emissions, industrial pollution, construction dust, crop stubble burning in neighbouring states, and unfavourable weather conditions.

Residents of the city lose over 8.2 years of their life by breathing in toxic air, a study released by The Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC) earlier this year has found.

Experts pointed out that the city’s 24-hour average air quality index (AQI) depends on data of all key pollutants, including PM2.5.

Misrepresentation of PM2.5 levels can then skew the AQI calculation for the entire city. Most pollution mitigation measures across regions are decided based on AQI. This includes the Commission of Air Quality Management’s call to impose restrictions under Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) for Delhi-NCR.

Stations such as Punjabi Bagh and Najafgarh were also flagged by DPCC as “pollution hotspots”. Missing data at these stations, in this case, would unintentionally lead authorities astray on localised mitigation methods.

“Missing data definitely affects the overall average, but more than that, it reduces the efficiency of taking direct action against pollution. When certain hotspots show lower PM2.5 levels than the reality, then pollution mitigation measures will also not be as strong there, even though they are necessary,” Dahiya said.

How is air quality measured?

Sensors in a monitor gather samples of multiple pollutants, among them PM2.5, PM10 (particulate matter smaller than 10mm), sulphur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide and ozone.

To determine AQI, levels of each pollutant measured are converted into sub-indices to make them comparable.

“The highest sub-index (among all pollutants) becomes the overall AQI of a location. If all pollutants are not measured by a station, the AQI is computed if at least three of the eight pollutants are measured, and if one of them is PM2.5 or PM10,” explained Mohammad Rafiuddin, programme lead at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).

The science of AQI, even CPCB admits, is not perfect.

“For Delhi NCR with multiple monitoring locations, the average value is used to indicate air quality. Air quality may show variations across locations, and averaging is not a scientifically sound approach. However, for the sake of simplicity, this method is being followed,” a statement on CPCB’s official website reads.

Why is data unavailable?

Through October till 5 November, there were only ten days that data from all 39 stations in Delhi was collected to arrive at the city’s overall AQI.

On most days, data from one to two stations was unavailable, and on key days—the day after Diwali, for instance—information from four stations was not present.

“There are two main possibilities for why data can be absent—either the station has shut down, and so none of the parameters are being recorded, or there’s an issue between recording of data and transporting it to the server in real-time,” George said, adding: “Either way, to miss 8-9 days of data in the capital city is unacceptable.”

Dahiya said another reason that data was not available from multiple stations on the night of Diwali could be that sensors get overwhelmed when pollution levels surge.

“Sometimes, it can happen that pollution levels are higher than what the sensor is able to monitor, so it shuts down or automatically turns off. But that is only possible if every sensor loses its data after reaching one particular threshold,” Dahiya said.

CPCB data from the early hours of 21 October corroborates this theory, though there’s uncertainty about what the ‘threshold’ may be.

Some of the sensors shut down just after recording a spike in PM2.5 levels. The last available reading for PM2.5 at Aya Nagar station was 892 micrograms per cubic metres (ug/m3) at midnight. At the station in ITO Delhi, the monitor logged PM2.5 at 923 ug/m3 before it went blank at 2 am.

Then, there were also stations like Bawana, which clocked PM2.5 at 994 ug/m3, but continued to record data through the night.

“Delhi has a large number of AQI monitors, but in cities with only one or two AQI monitors, this kind of data gap can really misrepresent the actual level of pollution,” said Dahiya.

CPCB, on its website, also referred to limitations of collecting, averaging and disseminating air quality data gathered at the stations. Some “technical” issues like long power cuts and maintenance problems can impact data flow, it pointed out.

Data gaps, Dahiya said, cannot become the norm.

“This is concerning because they can paint a picture of much cleaner air than we actually have. And if the gaps result from an issue with sensors, then it requires an overhaul and daily maintenance. Otherwise, lakhs of rupees spent on sensors and maintenance contracts will just be a waste of public money,” he said.

(Edited by Prerna Madan)

Also Read: Who was enemy no 1 at Delhi’s pollution protest? Capitalism