Elevated exchange rate, capital crunch due to GST, among others, seen as major causes for falling exports that has even alarmed the World Bank.

New Delhi: As the US-China tariff hostility threatens to snowball into a global trade war, India may find it harder to rescue its sagging exports.

World Bank data shows that India’s exports-to-GDP ratio has been steadily declining, pointing towards a failure to capitalise on the nascent economic recovery worldwide. With the threat of a trade war looming, that recovery itself could be stalled.

Exports are a key component of India’s GDP, contributing nearly 20 per cent to it in 2016. They were a major driver of growth before the 2008 financial crisis and made a positive contribution to India’s growth throughout 2010-11 and 2011-12.

However, their role has diminished in the past six years, according to the World Bank’s ‘India’s Development Update’.

The report expresses concern over the declining share of exports in India’s total GDP.

And although new data from the RBI, for the third quarter of the last fiscal year — October to December 2017 — showed exports growing by a marginal 4.48 per cent in dollar terms and 0.27 per cent in rupee terms over the same period in the preceding year, analysts said the outlook isn’t promising.

On the other hand, imports jumped 10.41 per cent in dollar terms and 5.96 per cent in rupee terms, worsening the trade imbalance.

This has led to a ballooning of India’s current account deficit to 2 per cent of GDP, which happens when the value of imports exceeds that of exports. Current account deficit stood at $13.5 billion during the October-December 2017 period, having increased from $8 billion the preceding year, the RBI data said.

Figure it out

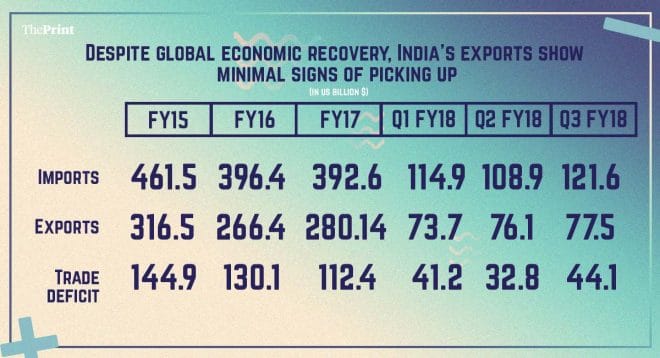

Exports fell from $316.5 billion in 2014-15 to $266.4 billion 2015-16, with a slight improvement in 2016-17 taking the figure to $280.14 billion.

Estimates by research firm Nirmal Bang have pegged exports for 2017-18 at $306 billion, with $227.3 billion already pulled off — an increase from the 2016-17 period, but still short of 2014-15 numbers.

The firm estimates 2017-18 imports to have been $466.2 billion, with the first three quarters’ imports adding up to $345.4 billion. The estimates for 2017-18 are much higher than the value of imports in the preceding three years.

This imbalance has resulted in a trade deficit of $118.2 billion in the first three quarters of financial year 2017-18, with estimates for the entire year pegged at $159.8 billion, up from $112.4 billion the previous year. The deficit was $144.9 billion and $130.1 billion in 2014-15 and 2015-16, respectively.

According to the World Bank’s report, a deficit in merchandise trade has caused the country to consistently run a current account deficit, despite a surplus in services trade and positive net transfers from abroad.

Reasons for sluggish exports

There are many and varied reasons for the poor performance of India’s exports sector despite improved global growth, according to Radhika Pandey, a consultant at National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

These include: an elevated exchange rate; the inability of Indian export products to successfully compete with rivals; a capital crunch caused by the ongoing transition to the Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime; an increase in imports because of a rise in demand for consumption goods; as well as a jump in oil prices.

Slower-than-usual disbursement of input tax credit has caused working capital constraints. The micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) sector, which contributes a major chunk to India’s total exports, has still not picked up after the disruption caused by the introduction of GST. And then there is competition from countries such as Bangladesh and Vietnam, which have, for example, surpassed India in apparel exports.

“India’s ability to fully benefit from the global recovery may be hampered by the rising cost of trade credit in the wake of the PNB scam and the risk of trade wars, just as the industry is reviving from the twin shocks of demonetisation and GST,” Nirmal Bang economist Teresa John said.

India’s nominal exchange rate — relative price difference between two currencies — rose by 4 per cent between January 2017 and February 2018, and the real exchange rate — the difference in relative price of goods in two countries — by 8 per cent between January 2016 and January 2018, Pandey pointed out.

While there have been calls for a more active exchange-rate policy to boost export, India’s exchange rate appreciation is in sync with global movements and has occurred despite an increase in forex reserves that have closely matched the pace of foreign direct investment (FDI) and foreign portfolio investment (FPI).

Way forward

According to Pandey, in the medium term, an atmosphere conducive to credit off-take by medium, small and micro enterprises (MSMEs) should be developed. The World Bank added in its report that India must significantly improve the competitiveness of Indian firms.