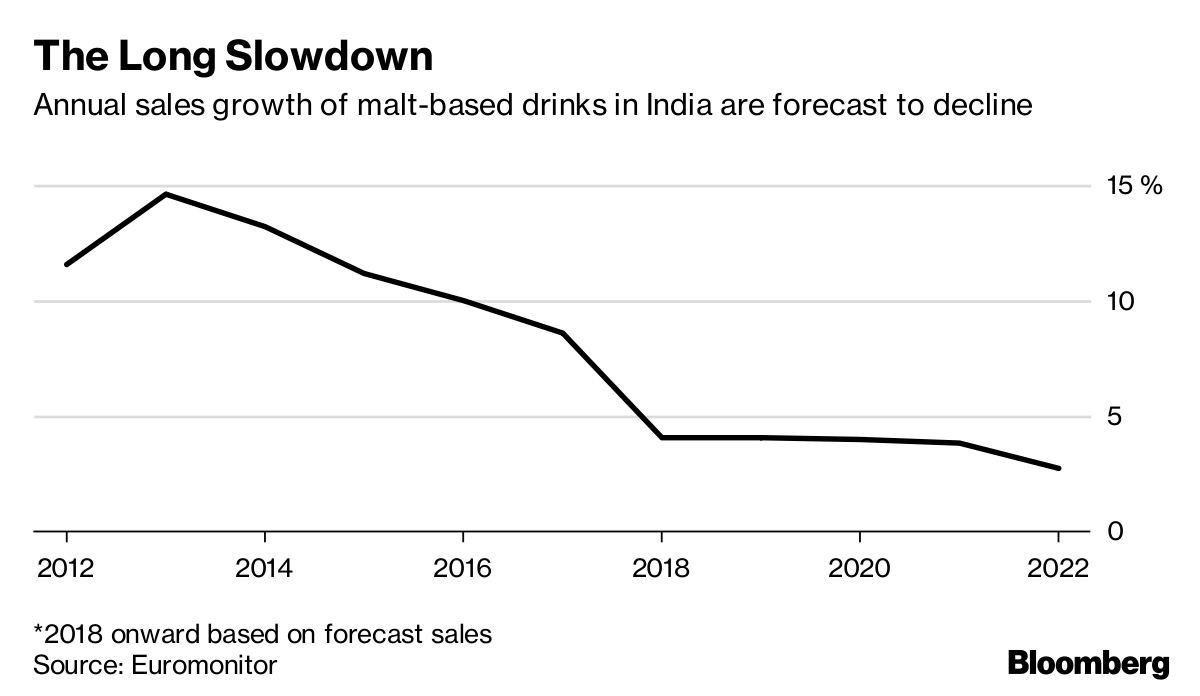

Annual sales growth of malt-based drinks in India are forecast to decline

For a century, children in India have been brought up on malt-flavored powdered milk drinks that they thought would help make them healthy and strong. Now the $1 billion industry is set for a shake-up after two of the biggest producers, GlaxoSmithKline Plc and Kraft Heinz Co. put the businesses up for sale and consumers switch to drinks with less sugar.

Malted milk drinks, which are as much as one-third sugar, have been breakfast staples of upwardly mobile families in India since soldiers brought GlaxoSmithKline’s Horlicks back with them after the First World War. Now, after a decade of double-digit growth, sales in India rose 8.6 per cent in 2017 and could drop to half that this year. By 2022, the market will expand by only 2.7 per cent, Euromonitor forecasts.

“Their core categories are growing at a much slower rate than they have been in the past,” said Amnish Agarwal, an equity analyst who follows the Indian consumer products market for brokerage Prabhudas Lilladher Pvt. in Mumbai. “That may be one reason they’re reducing their presence.”

GSK and Kraft Heinz were slow to adjust to consumers’ shifting demands in nutritional supplements and health drinks and have lost market share to competitors, he said. Still, GSK’s two brands, Horlicks and Boost, account for almost 60 percent of the market, according to market researcher RedSeer.

GSK is looking to divest the $4 billion Indian unit that makes Horlicks while demand for malt-based drinks in the country still shows growth. The company is on track to conclude a “strategic review” of its India consumer products business by the end of the year, spokesman Simon Steel said in an email. He said sales of health-food drinks are rising in India and GSK’s Horlicks and Boost have led the market with an 18 percent volume gain so far this year.

Kraft Heinz agreed last month to sell a portfolio of products that includes its malt drink Complan for almost 40 percent less than it was originally said to be seeking. The buyer, Cadila Healthcare Ltd., said in an emailed statement that Complan is a clinically proven health drink for children offering nutritional benefits, including protein from milk. Kraft Heinz and Cadbury Ltd., which makes the rival product Bournvita, did not respond to requests for comment.

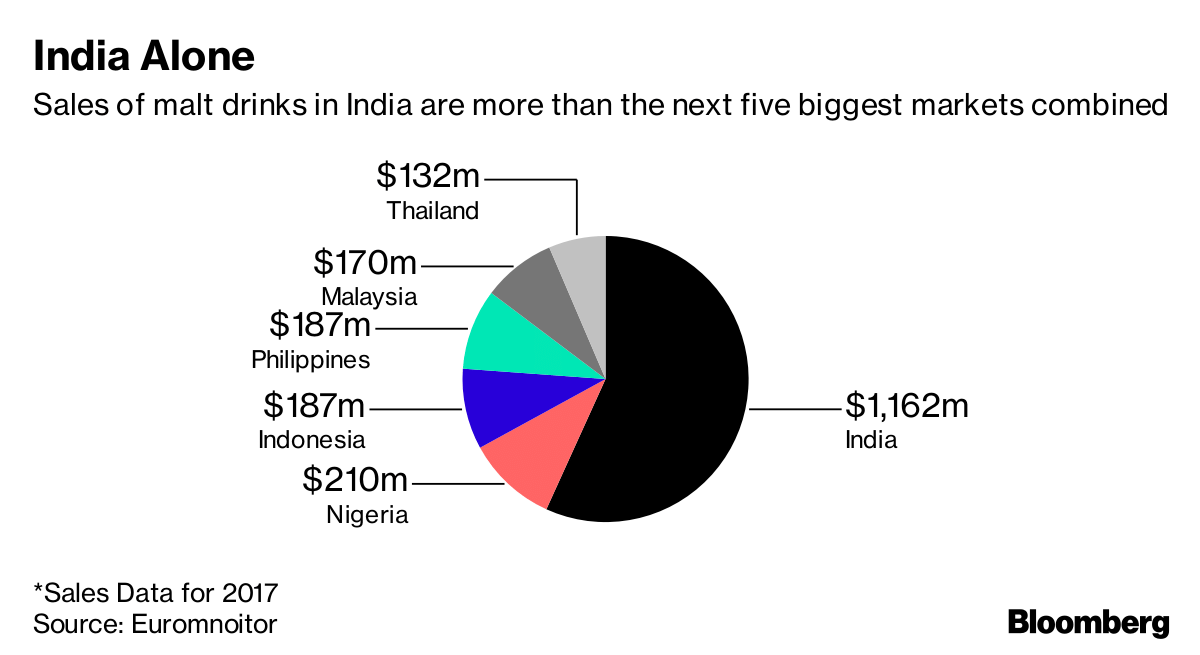

For decades, the manufacturers have marketed their malted drinks as health foods, with advertisements that promoted them as providing extra energy. India became the world’s biggest market for the products, even as their popularity declined elsewhere. Euromonitor estimates India accounts for almost half of global sales.

As a schoolgirl, Naaznin Husein started each day with a glass of Bournvita, which her mother believed would help her excel. That routine ended when Husein went to university to become a nutritionist.

“I think my mom thought it was healthy,” said Husein, 43, who now advises clients to focus on eating a balanced diet rather than taking supplements. “I realized I didn’t need any extras.”

To try to buoy sales, manufacturers are adapting the products to meet the shift in consumer tastes, offering versions that have less sugar and emphasizing the drinks’ protein and supplements.

“They’ve put some micronutrient powder in, but that doesn’t justify us giving so much sugar and carbohydrates to these children,” said Suparna Ghosh, head of community health at the Public Health Foundation of India in New Delhi.

India’s love of malted-milk drinks goes back to the 19th century, when the formulas were synonymous with corporal vigor throughout the British Empire. Horlicks, invented 140 years ago, was taken on British polar expeditions, distributed to athletes at the 1948 London Olympics, and included in aircrew escape kits during the Second World War.

With large parts of India having no regular access to fresh milk, parents turned to Horlicks and its competitors to fill the gap, creating a widespread habit that endured long after independence and even after fresh milk became widely available. Mothers now say they give malted milk products to children who don’t like the taste of plain milk, or to fill nutritional gaps, according to a June report from market researcher RedSeer.

Marketing campaigns such as Horlicks’ promise to make children “more tall, strong, sharp” appealed to anxious parents in a country where top universities get as many as 200 applicants for each place. Its Boost drink is endorsed by cricket legend Sachin Tendulkar.

With rising incomes in the country, India’s already crowded market for non-alcoholic beverages has seen an influx of new competitors. Established players like GSK have been joined in the past few years by new offerings from other global names like Danone’s Protinex Grow, aimed at teens, and Nestle Inc.’s reintroduction of its malted chocolate Milo drink, a top seller in countries including Malaysia and Singapore. Local producers are also ramping up offerings and the market is attracting newcomers such as upstart juice-drink maker Manpasand Beverages Ltd.

Most tout health benefits, from the addition of vitamins, to products aimed at local tastes. An increasing number target a new health concern among some Indian parents: protein, a nutritional necessity that is often lacking in a nation with among the lowest per-capita levels of meat consumption.

“Protein deficiency is something common in India because vegetarians don’t have very high sources of protein,” said Anand Shah, an analyst who covers consumer products for Axis Capital Ltd. out of Mumbai. “Other alternatives have emerged which GSK wasn’t particularly focusing on. One is the protein supplements.”

GSK launched a version of Horlicks with added protein earlier this year to compete with the proliferation of meal replacements, energy drinks and ayurvedic products based on India’s traditional system of medicine, according to Euromonitor.

Some parents though are simply taking nutritionist Husein’s advice: give your kids a balanced diet of natural foods.

“There used to be a perception that Horlicks or Complan is necessary to have good health and life standards,” said Sandhya Sathyaraj, whose 10-year old daughter goes to school in Mumbai. “In the past, milk and fresh juices were a luxury. That’s no more the scene. I scout for health drinks or organic products, but I prefer giving milk or fruit juices directly.”-Bloomberg