New Delhi: “Global hunger is on the rise, reversing decades of progress… The ripple effects of the conflict in Ukraine are extending human suffering far beyond its borders, threatening global hunger on an unprecedented scale.”

Yet, “62 new food billionaires have been created in the past two years. And billionaires in the food and energy sectors have seen their fortunes increase by some $382 billion over the past two years”.

These words were not uttered by a social activist raising an alarm — they come from Amina Mohammed, deputy secretary-general of the United Nations (UN), at the Economic and Social Council meeting held in New York on 20 June.

The war in Ukraine — triggered by Russia’s invasion on 24 February 2022 — disrupted supplies of wheat, fertilisers and edible oils in the Black Sea region, leading to a record surge in prices.

But food prices were already on the boil before the war began, driven by soaring energy and fertiliser prices, higher shipping costs, climate-induced production losses and massive stockpiling by China.

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), global food prices surged by 28 per cent in 2021 compared to the year before — the highest in a decade. By May 2022, food prices were 60 per cent higher compared to 2020 levels.

“Conditions now are much worse than during the Arab Spring in 2011 and the 2007-2008 food price crisis, when 48 countries were rocked by political unrest, riots and protests,” said David Beasley, executive director of the World Food Programme (WFP), earlier this month, while releasing a report titled ‘Hunger Hotspots: Early Warnings on Acute Food Insecurity’.

“We’ve already seen what’s happening in Indonesia, Pakistan, Peru, and Sri Lanka — that’s just the tip of the iceberg,” Beasley warned.

Also Read: As inflation breaks records, Modi govt plans to counter criticism ahead of anniversary & polls

Tip of the iceberg

According to the WFP, soaring food prices have worsened the hunger situation in countries like Kenya, Lebanon and Haiti, in addition to those in the Horn of Africa — blighted by a prolonged drought — and the likes of Syria and Afghanistan, both ravaged by conflict.

The surge in food prices also prompted countries to impose restrictions on exports to keep domestic food prices in check. Since the beginning of the war, over 20 countries have imposed export restrictions, impacting close to a fifth of the globally traded calories.

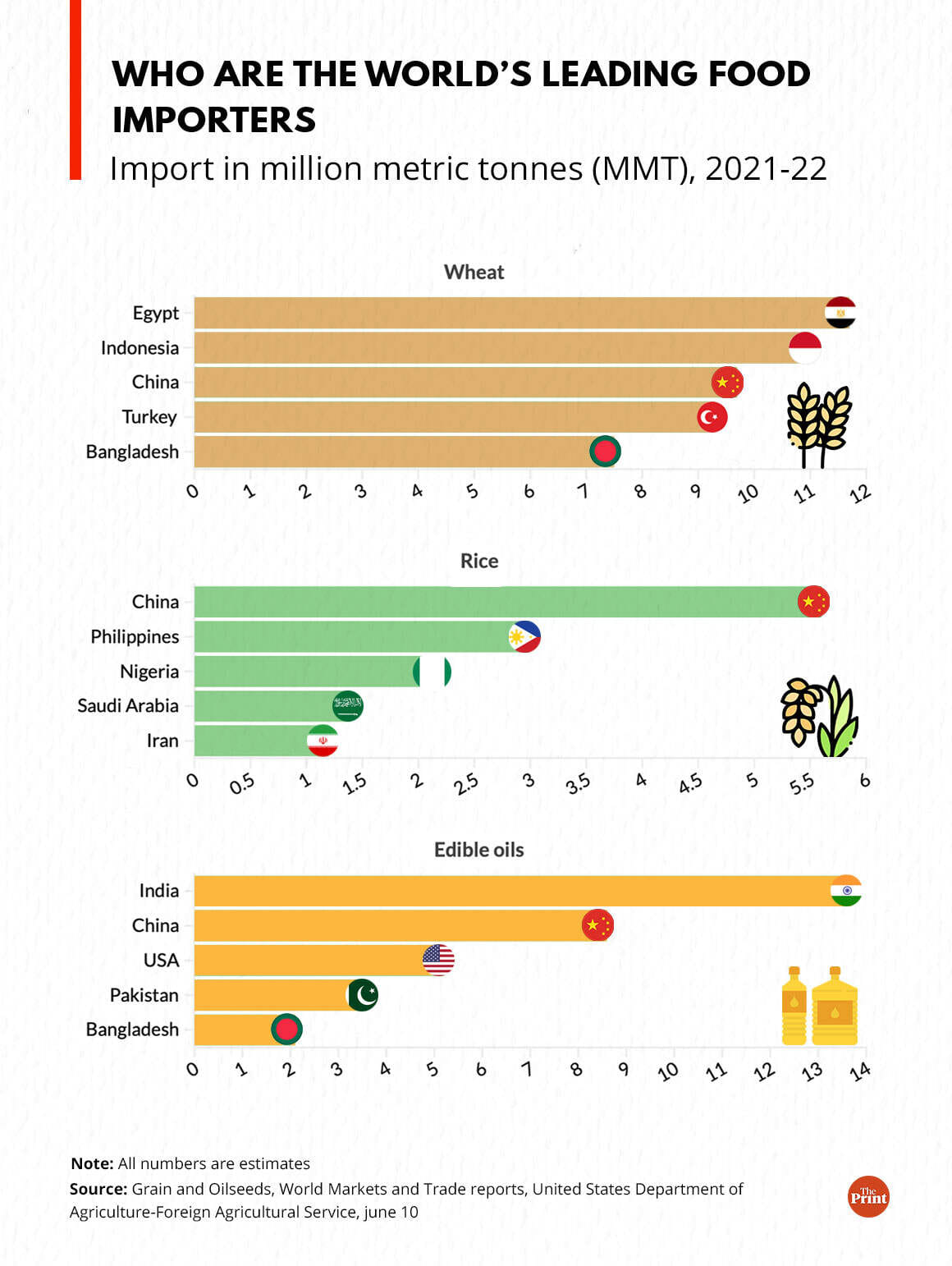

For instance, Indonesia, among the largest importers of wheat, curbed exports of palm oil in April. India, a large importer of edible oils, restricted wheat and sugar exports as domestic food prices soared. And now, the world is worried India, the world’s largest rice supplier, may restrict rice exports, worsening the global hunger situation.

China, which has been building massive food stocks via imports since 2020, restricted exports of fertilisers in October last year. Global food trade, post-war, has been swept by a wave of protectionism leading to more pain for food importers.

The fuel-food relationship

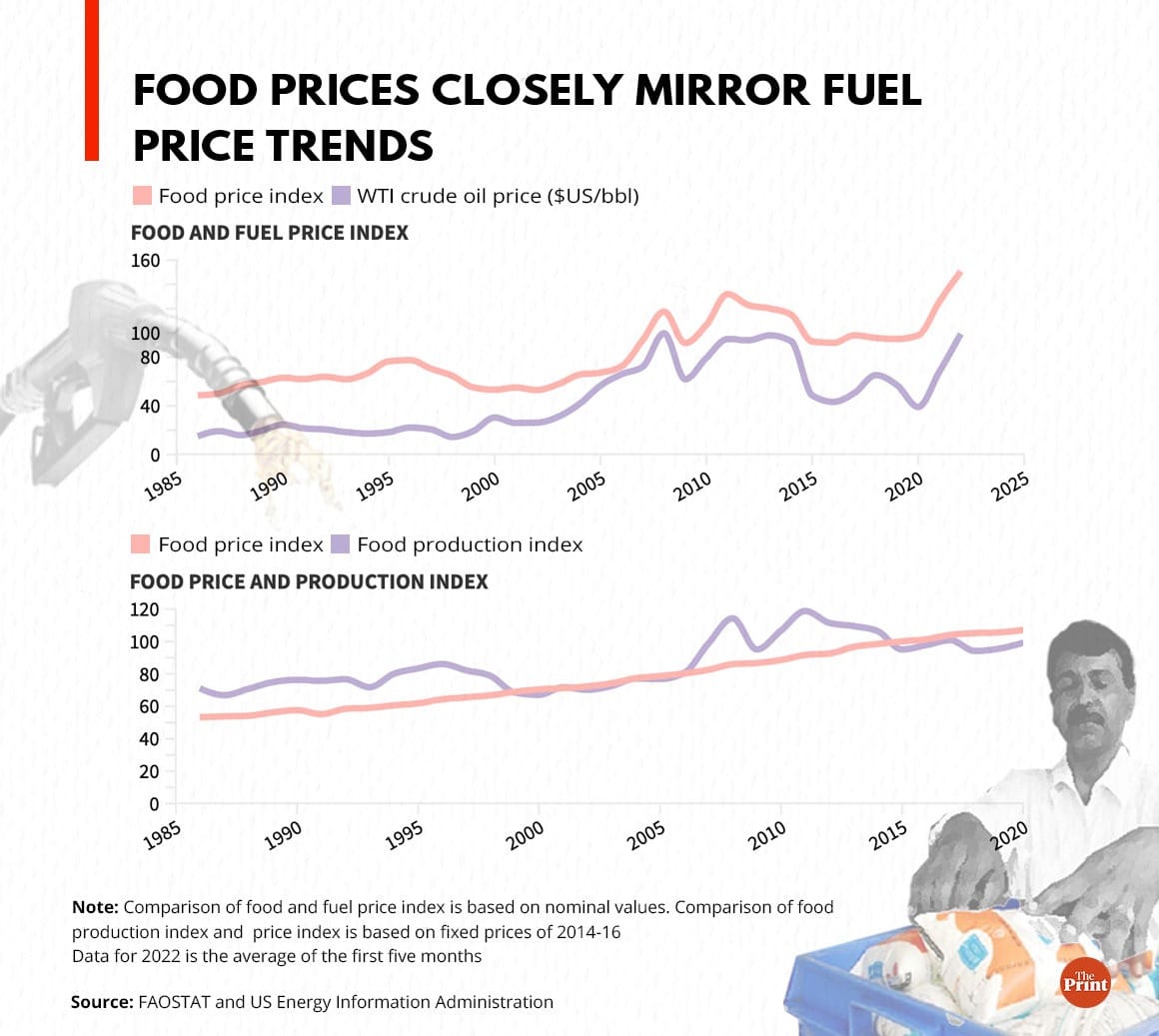

The supply disruption brought about by the Ukraine war only partly explains the surge in global food prices. Historically, global food prices closely mirror trends in energy prices, particularly crude oil.

The fuel-food association appears to be stronger than the food price-food production linkage.

Trade restrictions today affect almost one-fifth of total (food) calories traded globally, which further aggravates the crisis, observed the UN Global Crisis Response Group on Food, Energy and Finance brief earlier this month.

If the war continues and high prices of grain and fertilisers persist into the next planting season, it said, food availability will be reduced at the worst possible time, and the present crisis in corn, wheat and vegetable oils could extend to other staples, affecting billions more.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: Modi govt’s steps to fight inflation will help, but there’s a risk of unintended consequences