Jagatpur/Jayapura: It is peak wedding season in Jagatpur village in Rae Bareli, Uttar Pradesh. And while India’s economic slowdown has not stopped people from getting married, it has drastically shrunk 21-year-old Naushad’s once-booming tailoring business.

Until a year-and-a-half ago, Naushad would work at his traditional women’s wear boutique even after midnight on many days, and sometimes had to turn customers away. “There was no way I could cater to everyone then,” Naushad says.

But now, it is 7pm and Naushad is sitting idly at a friend’s shoe shop, waiting for any customer to approach his shop, which stands nearby. Sometimes, his wait stretches all day.

“Since 2018, everything is at an all-time low,” he says. “January is the wedding season, so people would come get lehengas and salwar suits stitched for the bride, for the bride’s sister, for the bride’s bua (paternal aunt)… Now, they find it hard to get one stitched for the bride,” Naushad says.

This is not just Naushad’s story. Across the UP countryside, farmers, manufacturers, retailers and labourers have similar tales to tell. They say the spiral began with demonetisation in November 2016 and the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax in July 2017, and once the slowdown hit the Indian economy, circa 2018, their ability to earn a livelihood and buy things for themselves and their families took a massive hit.

Also read: India’s painful ‘stagflation’ is now spreading to other emerging economies

Cutting spending wherever possible

Before the slowdown, Naushad would sometimes take a break from tailoring and set out for an evening stroll, and have a glass of juice and a samosa or an omelette with his friends. But now, he has to settle for a cup of tea. “When the income has reduced from Rs 250-300 a day to Rs 80-90 a day, who can afford juice?” he says.

It’s not just about the glass of juice Naushad can’t afford, or the fact that he has to borrow money from friends to buy a mobile data pack. His sister is about to get married in two months, and the family is busy paring the guest list to the bone.

The original plan was to order two quintals of gosht (meat) for the wedding celebration. But now, that’s been cut to one quintal. The wedding lehenga is being made from cheaper material, and fewer gifts are being purchased for the groom’s family.

Others in different parts of the state confirm that they’re trying to cut expenditure wherever there is scope — vegetables, clothes, electronics. In a state where more than 30 per cent of the population already lives below the calorie-based poverty line, and people have limited income-earning capacity, the effects are devastating.

Also read: Has IMF’s Gita Gopinath made India a convenient scapegoat by blaming it for global slowdown?

Worrying trends

India was the world’s fastest growing economy until 2018, posting a growth rate as high as 9.3 per cent in the first quarter of 2016. By September 2019, however, the quarterly growth rate had plummeted to 4.5 per cent — the lowest in more than six years.

Unreleased findings of the National Statistical Office (NSO) show that consumer spending in India fell by 3.7 per cent for the first time in four decades in 2017-18. The report stated that the decline in demand in the rural market stood at 8.8 per cent.

This has also meant that the rural consumption growth rate, which has historically grown three to five percentage points higher than its urban counterpart, has fallen behind for the first time.

Rural demand, which accounts for one-third of the overall Indian market, is in the doldrums.

Data from firms in the automobile sector and fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) have shown ample evidence of this downward trend. The Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM) revealed earlier this month that sales of passenger vehicles, commercial vehicles and two-wheelers in 2019 contracted by nearly 14 per cent compared to the year-ago period. SIAM attributed weak consumer sentiment as well as falling rural demand as some of the reasons for the negative growth.

FMCG firms are also seeing falling sales growth in rural areas. Marico, while announcing its second quarter results, said sales growth was flat at 1 per cent due to weak rural demand. Its popular hair oil brand, Parachute, reported a negative 1 per cent growth.

Marico, in a statement earlier this month, said its hair oil and coconut oil sales reported a marginal fall in the December quarter.

FMCG major Hindustan Unilever also said in a presentation that rural sales had fallen to half of urban sales in the quarter ending September. It reported a sales growth of 5 per cent in the period, as compared to 10 per cent in the year-ago period.

Also read: India needs a lot more policy stability to attract investors: Arvind Panagariya

When lunch becomes a luxury

Across rural UP, these are not just headlines or numbers but real stories.

Chinta Devi is a contract worker from Jayapura village in Varanasi district — a village adopted by Prime Minister Narendra Modi under the Saansad Adarsh Gram Yojana, a scheme for parliamentarians to develop model villages.

Chinta Devi has found a heart-breaking solution to cutting household expenditure — she doesn’t give lunch to her children anymore.

“We cannot afford three meals a day… Earlier, when they would come from school, I would make dal-chawal for them, but now we can’t afford it,” she says.

Om Prakash Patel, who runs a grocery shop in Jayapura, reveals that Chinta Devi is not alone — several families have adopted this technique to cope with the situation. The sales of everything from vegetables to oil to shampoos to dal (pulses) to biscuits have been hit, and Patel’s daily sales have more than halved in two years — from Rs 6,000 to Rs 2,000-3,000.

“Everyone’s in a very bad condition…When people are struggling to buy vegetables, how will they buy biscuits or Maggi?” Patel asks.

“Such an economic condition would have been unimaginable three-four years ago… Iss mandi ne gaon ke logon ke sab shauq khatm kar diye hain. (This slowdown has killed the hobbies of the people of the village).”

Between 2011-12 and 2017-18, the average monthly spending on food in rural areas across India has declined by 10 per cent, from Rs 643 to Rs 580. According to Nielsen market research, just the FMCG consumption in the rural market — which accounts for 36 per cent of the overall figure for India — has been the lowest in seven years.

Poor rural households in India, which spend more than 60 per cent of their incomes on food, are not able to afford nutritious foods like pulses, vegetables, milk and fruit because of their low spending capacity.

Internet data, which has come to be considered “a basic need” across villages, is becoming an unaffordable commodity. “We cannot live without data now…What use is a phone without internet?” asks Naushad. “But we are buying cheaper packs now… Sometimes I have to borrow money from friends to get my phone recharged.”

Anil Bajpai, who owns a mobile recharge and wrist watch shop in Jagatpur village, is suffering, in turn. As families struggle to make ends meet, his sales have dropped by 60-70 per cent, compelling him to cut down expenditure in his house.

“Earlier, parents would readily shell out money for their children’s mobile data… Now they tell them ‘either you study or use mobiles — we can’t afford both’,” Bajpai says.

Also read: Remove GST bottlenecks, boost rural spending among BJP’s 150 suggestions for Budget 2020

When farmers don’t prosper, how will businesses?

In Uttar Pradesh, 65 per cent of the workforce is employed in agriculture. But now, more people are taking to agriculture because of the staggering levels of unemployment.

Most people argue that there is no hope for a revival unless farm incomes grow.

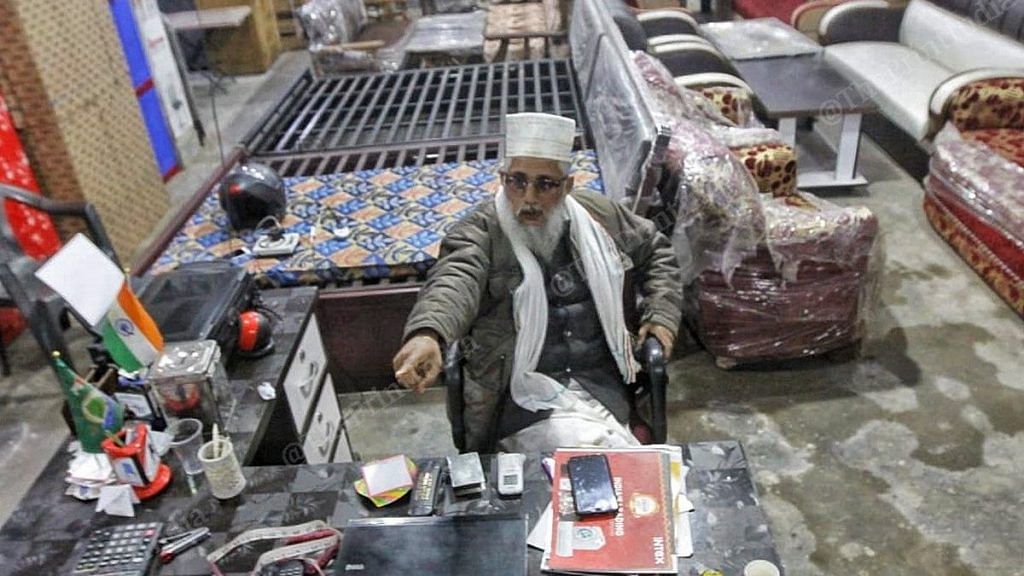

“Right now, there is farmer distress everywhere,” says 64-year-old Mehendi Hasan, who owns an electronics and furniture shop in Unchahar village, which falls on the border of Rae Bareli and Kunda districts. “In villages, when the farmer does not prosper, how will the businessman thrive?” he says.

Rural distress has been visible in India in the last few years. Two consecutive years of drought in 2014 and 2015, along with lack of remunerative minimum support prices, have aggravated the farmers’ plight, leading to a fall in real incomes and rise in debt levels. This has led to many state governments, including the Uttar Pradesh government, announcing a debt waiver.

The condition of farmers could improve marginally in the coming months, since there has been good production in the rabi season due to unseasonal rains in December. However, Siraj Hussain, senior visiting fellow at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, says unless the wider economy improves, there is no great expectation of much improvement in the agricultural sector.

On average, UP’s farmers don’t own more than one hectare of land, so the economic slowdown has meant a hand-to-mouth existence. This, in turn, has had an all-pervasive effect on the rural economy of the state.

Dowry on the decline

In Mehendi Hasan’s case, the wedding season would mean high profits, as families would spend large sums of money to buy refrigerators, washing machines, microwaves, sofas and king-size beds for dahej (dowry). But now, most families are cutting down on that expenditure too — perhaps the only positive in this sea of negatives.

“We have not sold a single refrigerator so far in 2020,” says Hasan, whose savings have gone towards paying off his distributor. “Earlier, during the wedding season, we would sell several in a day.”

Naushad’s family wanted to buy a sofa set, a king-size bed and a motorcycle for his sister’s wedding. “Now we will not be able to do that… Abbu (father) worries about this all day,” he says.

Asked if lesser dowry would mean harassment for his sister, Naushad said the groom’s family realises the condition of the economy. “Even the men are not earning as much as they did, so even their value has come down,” he says with a laugh.

People still continue to take loans for dowry, but say they have no option but to spend less. “Agar achhe din hote, toh hum bhi achhe se bida karte betiyon ko (if these were good days, we would’ve also given a better send-off to our daughters),” says Mewa Lal Yadav, who owns a fabric shop in Tharwai village in Prayagraj district, and whose 23-year-old daughter is about to get married in a few months.

Unlike many retailers, Yadav’s sales have not gone down since the slowdown hit the rural economy. But that is only because he reduced his margins significantly. “I realised soon enough that the only way to survive this is by reducing margins… Now to earn what I did after a sale of Rs 10,000, I have to sell items worth Rs 20,000,” he says.

Also read: US investors concerned over India’s economic slowdown, social unrest and Modi’s disinterest

The only booming business: Country liquor

There is, however, one business that is continuing to grow even amid the economic crisis — that of country liquor.

ThePrint spoke to several alcohol shop owners, who said their sales have only grown.

“If the sales a year or two ago were Rs 10-12,000 a day, they are easily Rs 17,000 now,” said Chandan Yadav, who owns a country liquor shop in Krishnanagar in Varanasi.

“Dekhiye, aadmi achhe waqt mein itna nahin peeta, jitna bure waqt mein peeta hai (Look, a man doesn’t drink as much in good times as he does in bad times),” he says, attending to men buying pauwa (quarter-bottles) from his shop for Rs 35-40 each.

Chetan Sharma, spokesperson for Mohan Goldwater Breweries in Unnao, added: “IMFL (Indian-Made Foreign Liquor) sales have slowed in the last one year, but the sale of country liquor has gone up substantially… Customers are increasingly shifting from IMFL to country liquor since it’s much cheaper.

“As alcohol is a product people consume during festivities as well as during troubled times, we can say the increase in volumes in sale is due to the negative sentiment in the market to some extent,” Sharma added.

Also read: Young, educated, jobless: These men in UP villages have nothing to do but play cricket