New Delhi: India’s public debt is stabilising after the pandemic surge, with the Centre making steady progress in reducing its burden while state finances remain mixed and less transparent, the Economic Survey 2025-26 and government records show.

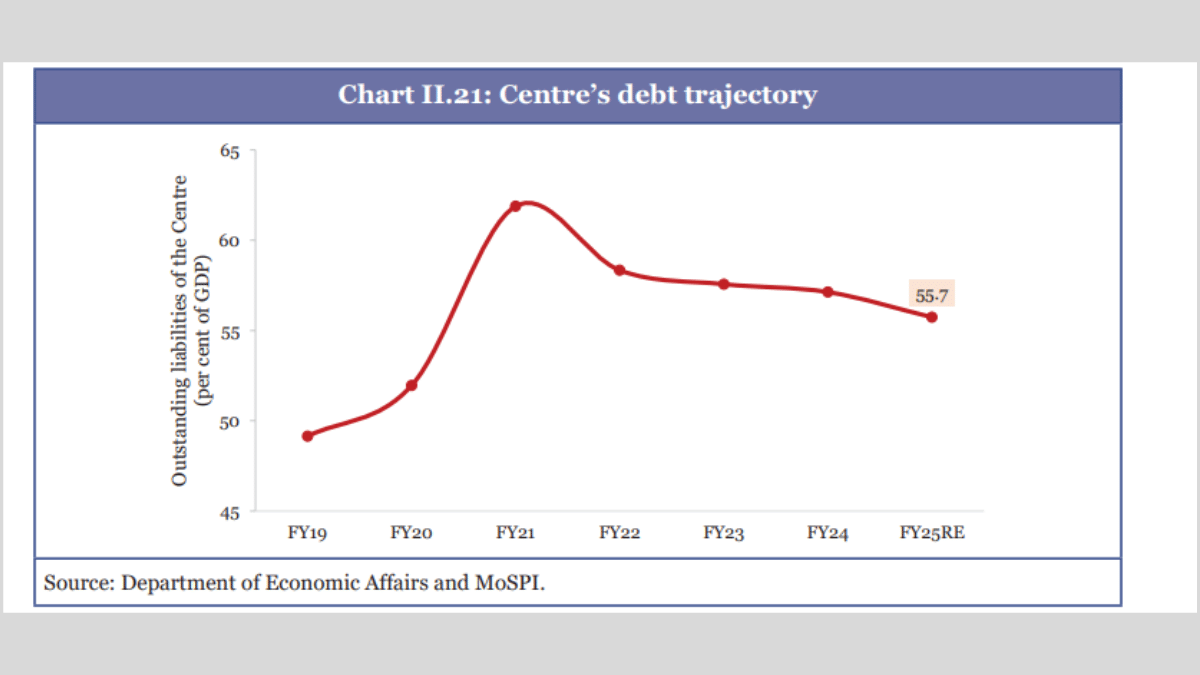

The Union government’s outstanding liabilities fell to around 55.7 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in FY25, down from a pandemic peak of around 62 percent in FY21, revised estimates quoted in the survey said. The Centre has committed to further reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio to approximately 50 percent by FY31, with a tolerance band of one percentage point.

This marks a clear turnaround from the steep borrowing increases in FY21 and FY22, when the government raised funds to finance pandemic spending and bring off-budget items onto the books.

Debt-to-GDP ratio indicates a country’s ability to pay back its debt by comparing what the country owes with what it produces. The higher the ratio, the less likely that country is to pay back its debt. A ratio in 60 percent or lower, comprising 40 percent for the central government and 20 percent for state governments, is considered moderate for large economies like India.

Data in the Economic Survey showed that India’s fiscal deficit has narrowed from 9.2 percent in FY21 to a target of 4.4 percent in FY26, while the proportion of capital spending in total expenditure increased, signalling the end of pandemic-era spending patterns.

The government also shifted its strategy away from the old Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) framework’s rigid 3 percent deficit target towards a medium-term debt-to-GDP anchor.

It believes this approach provides more flexibility in a volatile global environment than a legislative target that has been breached more often than kept. “The government’s medium-term goal to achieve a debt-to-GDP ratio of 50 ± 1 per cent by FY31 reflects a deliberate effort to strengthen overall debt sustainability while preserving policy flexibility in an uncertain global environment,” the survey said.

Also Read: India’s tech ambitions need private sector investment in R&D. Budget 2026 holds the key

Borrowing costs down

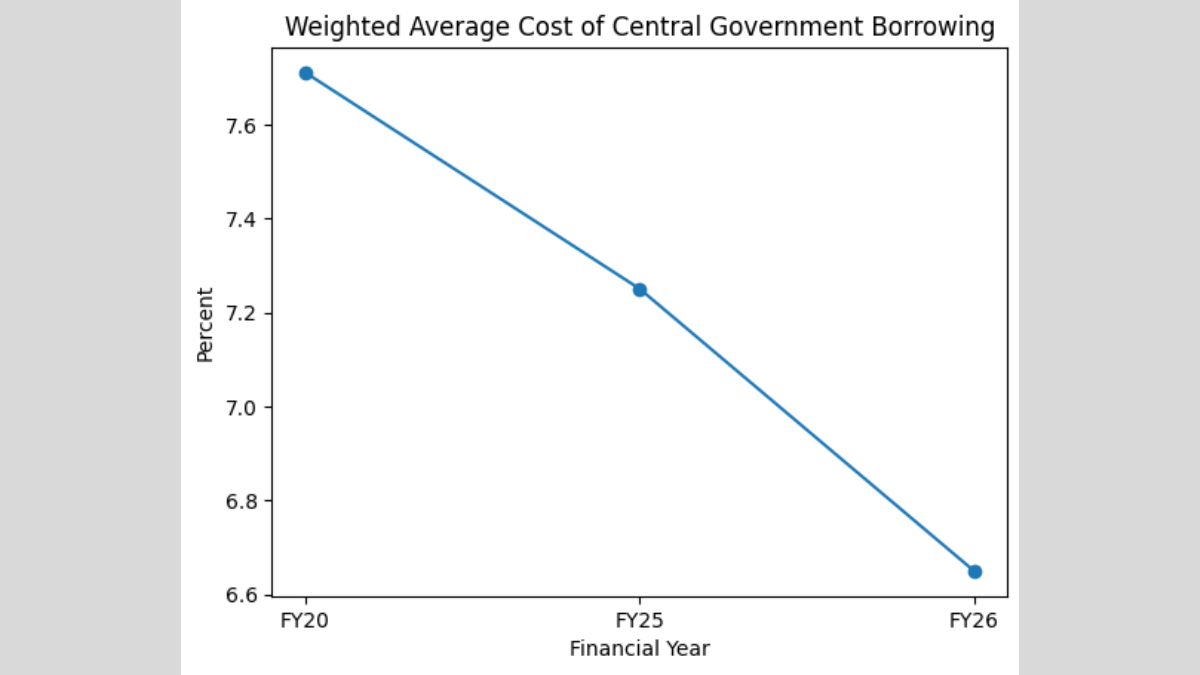

The weighted average cost of new borrowing (WACB) declined from 7.11 percent in FY25 to 6.65 percent in FY26, the Economic Survey said, calling it Centre’s “calibrated issuance” approach. WACB is the average interest that the government has to pay for all of its debt.

The Survey also pointed out that the government has placed almost half its new debt in maturities longer than ten years, shielding itself against rollover risks.

Only around 27 percent of outstanding debt is scheduled to mature over the next five years, with the weighted average maturity of new borrowings staying near 19 years. (Weighted average maturity of new borrowings determines the average time – years or months – until new debts, bonds, or loans must be repaid.) This means that only 5.4 percent of the existing debt will be carried on to the next financial year under less favourable market conditions, according to the Economic Survey 2025-26.

External debt manageable

India’s external debt, according to government data, stood at roughly $746 billion in September 2025, ranking among the world’s top borrowers in absolute terms. But, this includes private sector borrowings and is not a direct indicator of sovereign fiscal risk.

The government’s external liabilities account for just 2.6 percent of GDP and less than 5 percent of total government liabilities. Most foreign-sourced external debt is on concessional terms from multilateral institutions.

The survey further pointed out that India’s foreign currency reserves exceeded $701 billion as of January, providing a cushion for about 93 percent of total external debt—an advantage few other emerging markets enjoy.

The distinction between external debt and domestic public debt is crucial, particularly for international comparisons. India’s debt challenge is not so much an external solvency issue as it is a domestic fiscal management problem.

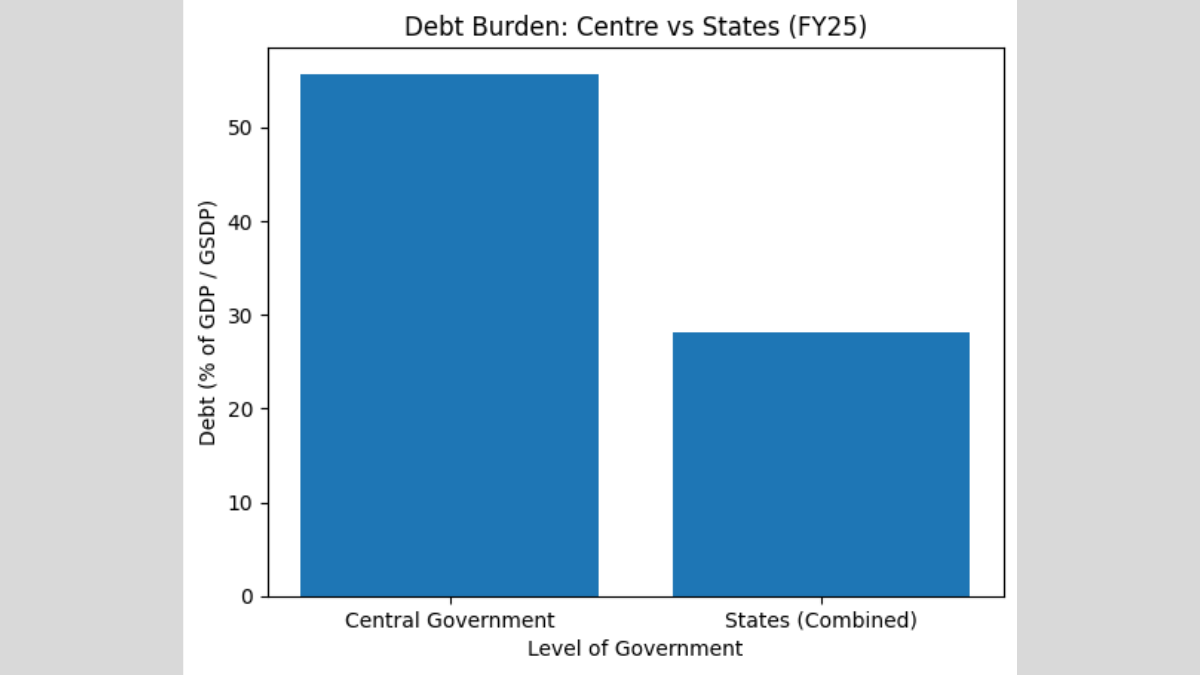

States present uneven picture

While the Centre’s debt profile appears relatively predictable, state finances are far less certain. The combined debt of all states and Union territories has been on an upward trend for the last ten years, with a dramatic spike during the pandemic followed by partial consolidation.

For 28 states combined, the debt-to-state-GDP ratio is estimated at around 28.1 percent in FY25, with interest payments absorbing roughly 12.6 percent of revenue receipts in the fiscal year.

But these overall numbers mask substantial differences, with some states enjoying low debt levels while others face limited fiscal capacity due to high debt service obligations relative to revenues.

Odisha, Maharashtra and Gujarat are the top-performing Indian states regarding debt management, consistently maintaining the lowest debt-to-GSDP ratios, often below 20 percent. On the other side, Punjab, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Himachal Pradesh, and Meghalaya were among states with highest debt-to-GSDP ratios, in the 40-57 percent range, this fiscal year, IndiaSpend reported.

The Economic Survey pointed to “weak differentiation” in the State Development Loan (SDL) market, meaning the market is not yet penalising fiscally profligate states or rewarding prudent ones. SDLs are securities issued by state governments to fund their fiscal deficits. “… borrowing costs do not sufficiently reward fiscally stronger states or penalise weaker ones,” the survey said.

Also Read: More states giving out cash transfers. They aren’t substitutes for investments: Economic Survey