Mumbai: O’er the hills and far away, as the redcoats trudged through Flanders, Portugal, and Spain in the service of King George, agents back in London pored over their ledgers, handling pay, provisions and other affairs. And one firm of such agents went on to grow with the Empire, centring itself in India. After the Empire’s fall, it would reinvent itself as a travel empire in its own right, sprawling across the globe.

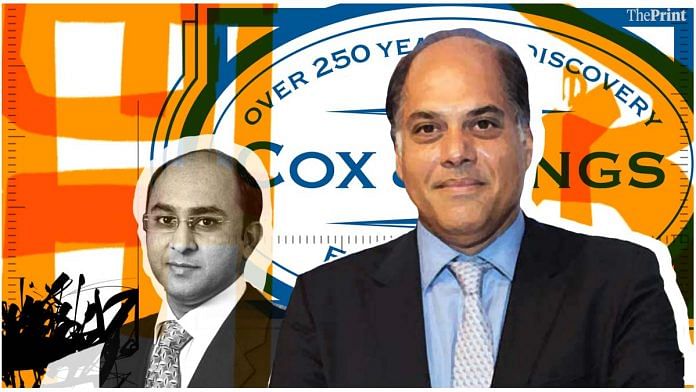

But today, this 264-year-old story seems at an end, with Cox & Kings Ltd (CKL) being liquidated, and its top promoter, Stanford-educated, jet-setting Peter Kerkar, whiling away his days, not at his Irish holiday home, but in Mumbai’s Arthur Road jail.

A battery of investigators — from the Mumbai Police’s Economic Offences Wing to the Enforcement Directorate (ED), the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), and the Ministry of Finance — have filed as many as 10 cases against Kerkar and the company’s former chief financial officer (CFO), Anil Khandelwal — also jailed — over alleged fraud amounting to more than Rs. 5,500 crore.

Before its fall began in 2019, Cox & Kings — a pioneer in the Indian travel industry — had spread its wings, with offices in some 27 countries, catering to more than five lakh customers annually. On the outside, things had never looked so good, and travel was booming on the eve of the pandemic.

But the rot had set in nearly a decade before, according to investigators and experts, as Kerkar overstretched the firm’s finances in his drive for expansion, opening offices and snapping up hotels the world over.

When the company began to default on its loans in 2019, its creditors took note, and asked Big 4 firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) to carry out a forensic audit. In its draft report, PWC said, “CKL had indulged in falsification of financial statements by overstating their sales figures/ debtors and understating debt position. Several fictitious transactions were also reported, projecting a wrong financial position of CKL.”

PwC also reported that CKL had siphoned a large sum of monies, through suspicious loans and advancements, to various “related parties”, with no proper approval or documentation.

It snowballed from there. Cox & Kings was declared bankrupt in November 2020, and the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) ordered its liquidation in December last year.

Meanwhile, in late 2020, the ED summoned Kerkar for questioning, and he was then arrested and imprisoned. He has been denied bail ever since.

The Economic Offences Wing (EOW) of the Mumbai Police took charge of the case in 2021. In a report, the EOW stated that the firm’s balance sheets had been manipulated since 2010, when nearly 15 shell companies were formed to rotate money.

Rejecting Kerkar’s bail plea in April 2021, a special court set up under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) observed, “This is the tip of the iceberg in this ocean of money laundering, which may sink the entire financial system of the bank/ financial institutions of the country.”

ThePrint reached out for comment via email to Kerkar’s sister, Urrshila Kerkar, one of the company’s directors, but had not received a response by the time this article was published. The article will be updated if she responds.

Also read: Cox & Kings created layers of onshore and offshore subsidiaries to siphon off money: ED

Insolvency proceedings

The National Company Law Tribunal (Bankruptcy Court) in Mumbai admitted an insolvency petition from a creditor, RattanIndia Finance, against Cox & Kings for its liquidation in 2019.

After bankruptcy was declared in 2020, lenders filed an application for the company to be liquidated in March 2021, and the NCLT admitted an insolvency petition from another creditor, Yes Bank, in May 2021.

After the company was unable to come up with a resolution plan, the NCLT on 16 December, 2021, gave orders to begin the liquidation process.

“It is a result of misjudgement where a business has gone wrong, and a case of fraud too,” said Ashvin Shetty, chief financial analyst with Marcellus Investment Managers, who assisted his firm’s founder, Saurabh Mukherjea, with the book Diamonds in the Dust, co-authored with Rakshit Ranjan and Salil Desai, where the financial auditing of Cox & Kings is detailed.

The investigation

Cox & Kings owes more than Rs 5,500 crore to investors and banks, and is one of Yes Bank’s top borrowers. The bank had alleged in its complaint to the Mumbai Police that between 2015 and 2018, Kerkar had taken loans that were never utilised for their ostensible purpose. The Mumbai Police are further investigating these allegations.

The PMLA court observed in April 2021 that as a travel and tourism firm, “they have no business to deal with the financing of other companies. When CKL is obtaining a loan from Yes Bank, Axis Bank, IndusInd Bank, Kotak Mahindra Bank for promotion of their business and expansion of it in India and abroad, questions clearly arise as to how they are diverting the funds to other companies under the head of loan.”

And so, the borrowed amounts weren’t used for their ostensible purpose, but for personal gain, the court observed.

Meanwhile, Kerkar in 2020 had complained to the Mumbai Police that some of his employees had conspired against him with officials from several banks, and diverted funds without his knowledge. The police filed two FIRs based on his complaint, which were later transferred to the EOW.

Then, in October 2020, the mystery darkened when a chartered accountant employed by Cox & Kings, who had been a witness in the proceedings, was found dead on a railway track in Kalyan. The police suspected suicide, although his family alleged murder.

Last month, the EOW filed a closure report for the cases filed based on Kerkar’s complaints, with Niket Kaushik, additional director general and joint commissioner (EOW), telling ThePrint that “they were false”.

“Yes, we have filed a closure report since we didn’t find anything in Kerkar’s complaints,” said Kaushik.

But Dharmesh Joshi, one of the lawyers representing Kerkar, told ThePrint, “The complaint copy of the closure report has not been submitted to us yet. It is a single-page letter served upon Peter, saying that we have closed the case. But no supporting documents are being served to us. Once we receive them, then there is a provision to challenge it.”

According to the EOW, Cox & Kings was a complex web of entities, which set up several pockets to siphon off funds. It had created about 15 shell companies as early as 2010, when it opened separate bank accounts for each of those firms. And all the transactions involving these companies — ostensibly concerning ticket sales — were only on paper, the investigators allege.

“There was a smokescreen created for the investors, where they couldn’t decipher it,” concluded Shetty.

But how did this historic, world-bestriding firm fall to such a nadir?

Also read: Credit rating companies are still missing big defaults by Indian firms

Sunshine days

Cox & Kings traces its origins to the year 1758, when Lord Ligonier, colonel of the 1st Foot Guards, appointed one Richard Cox as his agent to handle the affairs, pay, and other obligations of officers stationed overseas. Over the years, it became an integral part of the British Army, and got its fingers into a number of pies — it’s been a printer, publisher, banking firm, insurance agent, travel agent, and cargo agent, and even had its own ships.

In the 20th century, the company was incorporated as Cox & Co in London, and went on to absorb Henry Kings & Co, a small bank with Indian interests — hence the name Cox and Kings.

But by the early 1980s, the company’s foreign owners were under regulatory pressure to divest and ‘Indianise’, and a majority stake was promptly snapped up by Ajit Kerkar, a London-trained hotelier married to a Swiss interior designer, together with British PR executive Anthony Good. As head of Tata Group’s hospitality wing, Ajit Kerkar was credited with expanding the group’s Indian Hotels empire — one of Cox and Kings’ biggest clients in India.

In 1997, Ratan Tata ousted Ajit Kerkar from Indian Hotels. Saurabh Mukherjea, in Diamonds in the Dust, says the Tata group claimed that the Kerkars had increased their control of Cox & Kings India — in which other Tata executives had also bought shares — through dubious means.

But Ajit’s children, Peter and Urrshila, would in later years transform the company. With economic liberalisation in India, the travel industry boomed — and so did Cox & Kings’ business.

Peter joined the firm’s London office in 1986 and graduated to become an executive director in 1994, while Urrshila looked after the Indian operations. Between 2006 and 2009, the company made a series of acquisitions of small and medium-size firms.

On the eve of Cox & Kings’ Initial Public Offering (IPO) in 2009, the Kerkars held close to 78 per cent of its outstanding capital, with net revenues at Rs 286 crore and an upward profit of Rs 62 crore — making it one of the biggest and most profitable travel companies in India.

The IPO of Rs 509 crore was oversubscribed by a factor of six, and by FY2011, the company had a net cash surplus of more than Rs 300 crore.

According to Diamonds in the Dust, throughout the 10 years between 2009 and 2019, since the company was listed publicly, it was regarded as a “professionally managed listed entity with a solid business”.

Meanwhile, the travel industry was growing apace. According to the Ministry of Tourism’s website, the number of foreign tourists arriving in India grew from 12.8 lakh in 1981, to 16.8 lakh in 1991, 25.4 lakh in 2001, 65.8 lakh in 2012, and hit 1.093 crore in 2019.

The number of Indian nationals departing the country was 19.4 lakh in 1991, which rose to 149.2 lakh in 2012 and 269.1 lakh in 2019.

“The industry was flourishing and Cox & Kings were on top. 2019 was the best year for tourism in India before the pandemic hit,” said Subhash Goyal, chairman of Stic Travels and former president of the Indian Association of Tour Operators. But it was all set to unravel.

Also read: Why e-payments firm BharatPe’s board wants to oust Ashneer Grover, who co-founded the company

Dark times ahead

In 2011, Cox & Kings announced its ambitious acquisition of British educational tour group Holidaybreak for Rs 2,770 crore — a 36 per cent premium over the group’s then market price. It was a package deal — the buyer also took on Holidaybreak’s outstanding debt of Rs 1,132 crore, in an acquisition that Shetty termed a “miscapital allocation”.

As a result, from a position of net cash surplus, the company’s net debt-to equity ratio shot up 3.1 times by the end of FY2012.

With mounting debt, Cox & Kings began defaulting on its scheduled loan repayments. In 2019, the company was unable to repay a commercial paper worth Rs 150 crore, despite having cash and liquid investments to the tune of Rs 1,666 crore.

This became a trend — and finally, in October 2019, Anil Khandelwal, the company’s chief financial officer, resigned, and the NCLT admitted an insolvency petition, thus “bringing an end to the centuries-old journey of Cox and Kings, including 40 years under the Kerkars,” write the authors of Diamonds in the Dust.

Rising expenses, poor cash flow

According to Goyal, Cox & Kings was unable to strike a balance between expenses and profits.

“There are three reasons whenever any business fails. One is overtrade (overspending). They increase the expenses and don’t cut costs. In the case of Cox & Kings, they opened offices all over the world — Japan, UAE. They all cost money,” he said.

“Also, Peter and Urrshila had invested in hotels in Europe with the cash that they had, rather than using it for business or keeping it in reserve. And when they needed funds, that was not available. This is my reading,” he said.

In contrast, competitors such as Thomas Cook and SOTC had always maintained their expenses at a lower level than profits. That balance was important, he added.

An analysis of the company’s financials by Marcellus Investment Managers suggested that Cox & Kings indulged in fraudulent practices that were, surprisingly, ignored by lenders and equity investors.

“Any business that has run for three decades should have been a self-sustaining business, but despite that, they went on raising capital, which means a problem with the business model — or you are siphoning off the money. Investors could have seen many such things and detected fraud,” said Shetty.

The company’s cash conversion was very weak, writes Mukherjea. From FY2011 to FY2018, only 60 per cent of the cumulative earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation (EBITDA) was converted to operating cash before taxation.

“Service industry companies are cash-generating companies as they are asset-light models because you don’t have to invest in buildings and other assets. So, by definition, service industry companies generate cash flow,” explained Shetty.

“Generally, everybody focuses on the profit and loss account and nobody looks at the cash flow statement. One typical pattern with fraudulent companies is that the profit and loss statement looks good. But Cox & Kings hasn’t generated free cash flow — and if any company doesn’t generate free cash flow say, at least twice or thrice in 10 years, then there is some problem,” he said.

“I think the investors didn’t focus on this aspect. This should have led to questions from them,” he added.

Also read: 5 years, 28 banks, Rs 23,000 cr debt — how ABG Shipyard pulled off ‘India’s biggest bank fraud’

‘Related party transactions’

Another factor was ‘related party transactions’ — with connected companies — which accounted for 92 per cent of Cox & Kings’ total revenues and 81 per cent of total purchases in 2018. The largest among these was Ezeego OneTravel and Tours, an online portal for booking flights, hotels and other travel needs, owned by Peter Kerkar. Ezeego was never able to scale up to wipe out its losses, which began in FY2017.

Investigators say this money was siphoned from Ezeego to Redkite — a company owned by the Kerkars, Khandelwal and internal auditor Naresh Jain.

However, Kerkar’s lawyers submitted in court that the ED’s allegation “does not hold water as the ED has desperately tried to accuse him by mixing up the related party transaction and transactions with the companies owned/ directed/ promoted by Ajay Ajit Peter Kerkar and Mr Naresh Jain. And that the annual report of 2017-18 spells out that the money went to Mauritius and other foreign entities.”

Cox & Kings had also been doing a lot of equity dilution — with the IPO, global depository report (GDR) issues, and qualified institutional placement (QIP) issues — which was a cause for concern, said Shetty.

As a result, by 30 June, 2021, the shareholding pattern of the company was such that the promoters held only 12.2 per cent of the shares.

“Retail investors can be understood as they don’t have resources within them to realise, but how did large institutional investors take the bet? Before the QIP, there was cash available with the company, so the question could have been raised as to why the cash was not used to pay off the debt,” said Shetty.

(Edited by Rohan Manoj)

Also read: Antrix-Devas case: What was the dispute & why SC upheld NCLAT order to wind up Devas for fraud