What should’ve been simple question of deciding who’s willing to shell out the most for a prized asset has become a complex debate.

It’s a forlorn sight when emerging markets stage a creditable performance and investors don’t turn up. It’s miserable when patrons head for the exit after denouncing the play as a flop.

While it’s still grappling with the second problem, India also has a third. It has a good show going, for which the likes of ArcelorMittal are reluctantly paying a $1 billion cover charge, but legal plot twists are spoiling the entertainment.

The drama in question is the $7 billion bankruptcy of Essar Steel Ltd. The 420 billion rupee ($5.8 billion) offer for the asset announced by ArcelorMittal on Monday is unexpectedly bold. If accepted by creditors, it would see their secured principal claims repaid in full, bringing relief to a banking system weighed down by more than $200 billion in stressed loans.

The timing is also nice. With the rupee hitting record lows amid the emerging markets sell-off, India should be welcoming hard-currency offers like ArcelorMittal’s, which is higher by 50 billion rupees than the second bid by Numetal Ltd., a consortium backed by Russia’s VTB Capital.

Additionally, the London-based Indian billionaire Lakshmi Mittal is being arm-twisted into ponying up $1 billion to settle two other, unconnected nonperforming loans to Indian banks. This is only because he badly wants a big presence in his home country, and he – or parties connected to him – won’t be eligible for Essar’s 10-million-tons-a-year plant without the side payment.

That’s the law, as he was told recently by the appellate authority of India’s insolvency tribunal. Mittal is challenging the ruling in India’s Supreme Court on the grounds that eligibility norms are not being uniformly applied. Numetal is being permitted to stay in the race for Essar by simply ejecting the latter’s ineligible founders – the Ruia family – from its consortium. But when it comes to ArcelorMittal, which has similarly sold its stake in Uttam Galva Steels Ltd., the appellate body is insisting that it clear the company’s nonperforming loans first.

India’s banking regulator was hoping in June last year that the country’s new insolvency law would live up to its promise of resolving big-ticket corporate bankruptcies in nine months. However, in Essar’s case, 15 months have gone by, and it looks like bidding will start afresh.

More frustratingly, whatever the bidding outcome, a fat check for loss-laden banks will remain stuck in legal tangles. What should have been a simple question of deciding who’s willing to shell out the most for a prized asset has become a complex debate about who’s deemed eligible to pay anything at all.

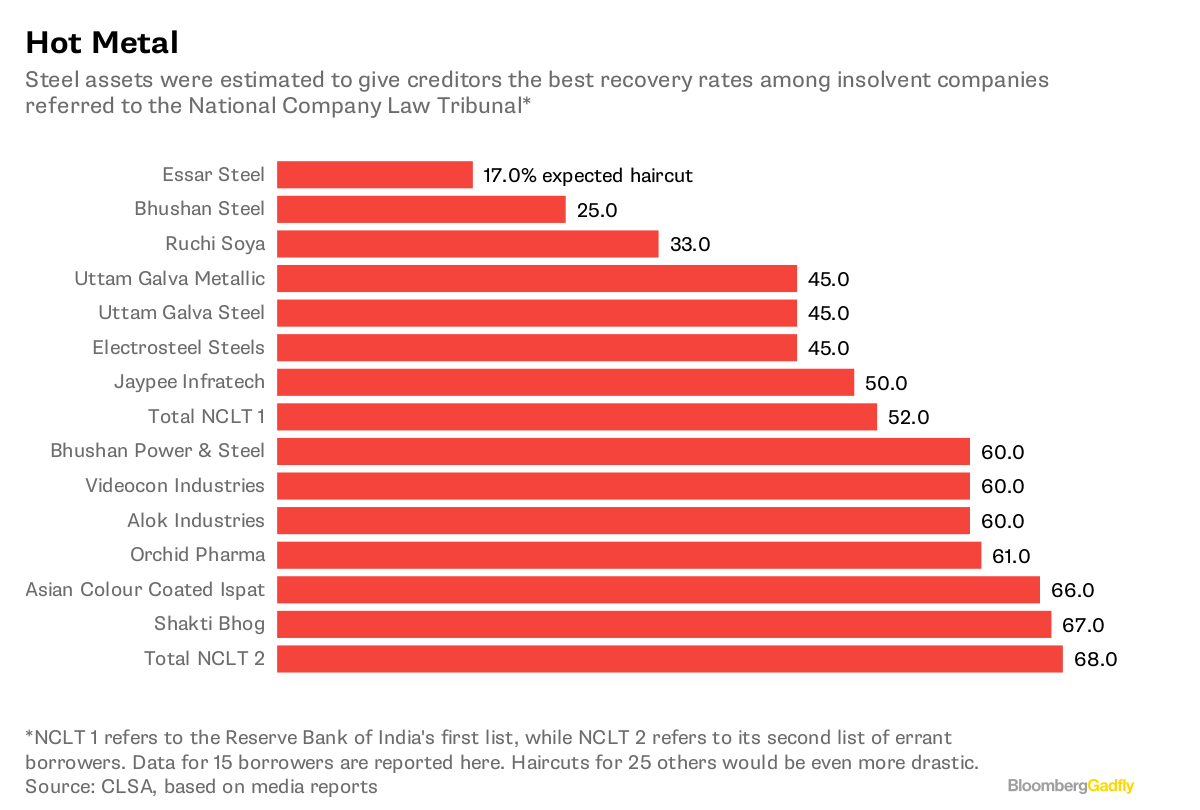

Creditors are biting their nails. Steel assets are giving them the best recovery rates on nonperforming loans; they will pray the sale gets done while the good times last.

India’s new bankruptcy law will eventually become stronger as it gets tested by tricky situations. The precedent set by Essar will send a message to the Ruias and other corporate maharajahs on how seriously they should take the risk of losing their crown jewels if they don’t settle overdue loans.

Yet given the urgency to sort out the banking mess, the lesson is also a costly one. The value of Essar Steel has gone up over the past year because the industry’s economics have improved. Besides, the plant is of strategic interest to Mittal, a global steel tycoon who has never been allowed by rivals to build a sizable business in his home country. Most other – and especially smaller – bankruptcies won’t be blessed by these special factors, and will lead to liquidation if their original owners can’t buy the assets back in partnership with vulture funds and other specialist investors.

Let the delay in selling Essar be a wake-up call. India’s insolvency law needs a further tweak to make it more about money and less about morals.-Bloomberg