“And all the roads jam up with credit

And there’s nothing you can do

It’s all just bits of paper

Flying away from you”

— Road to Hell: Part 2, Chris Rea

Net household financial savings improved in fiscal year 2024-25, but the Reserve Bank of India’s Financial Stability Report 2025, released late last month, tells another story – that of deteriorating household debt.

The report points to increased borrowing by households, specifically for consumption, and higher debt write-offs by banks and defaults recorded by non-banking financial companies (NBFCs).

Analysis suggests these metrics are rising because jobs and salaries aren’t increasing fast enough to match the cost of living, forcing households to resort to debt. Then, there’s the trend fuelled by social media’s illusion of prosperity, which convinces many to take loans for sustaining a lifestyle they can’t afford.

Savings up, debt up too

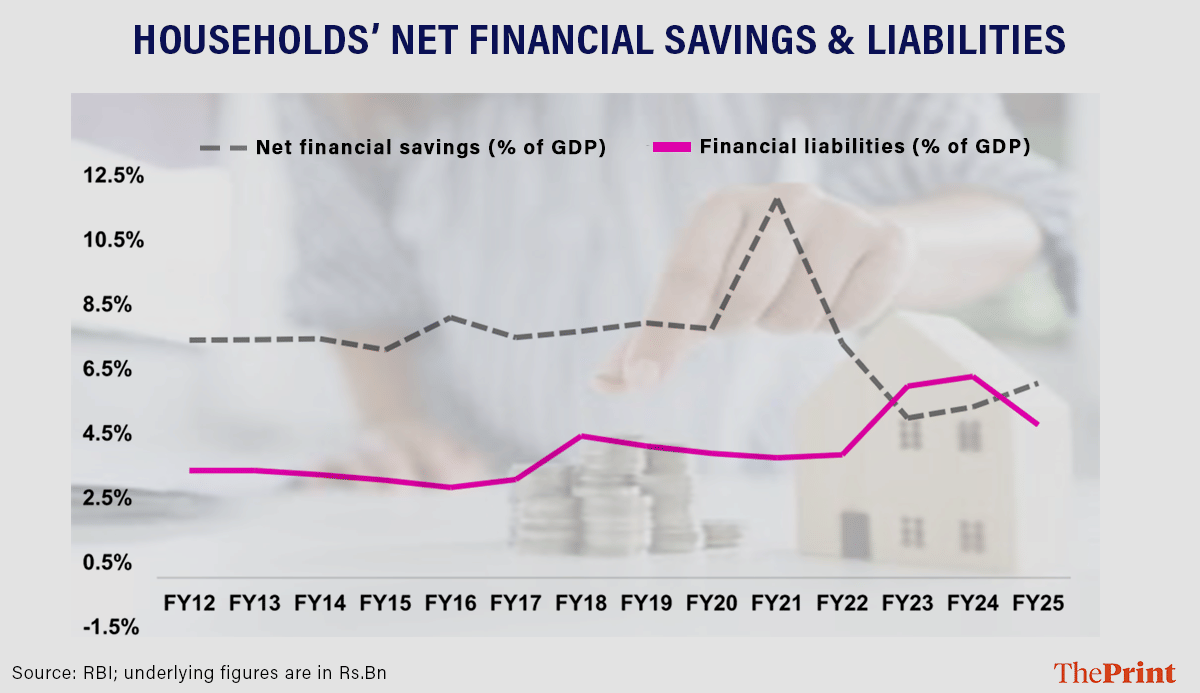

Net household savings in India has been a point of concern over the last couple of years. This figure—which translates to gross financial assets of households minus household liabilities, as a percentage of GDP—had plunged to a 50-year low in FY23.

The good news is that net household savings rose as a percentage of GDP in FY25, largely because of a slower increase in liabilities (see chart below), a fact also echoed by some of the country’s largest banks, which say their loan book growth slowed down significantly in FY25.

But the central bank’s FSR also showed two sets of metrics that worsened over the past year.

- Non-housing retail loans

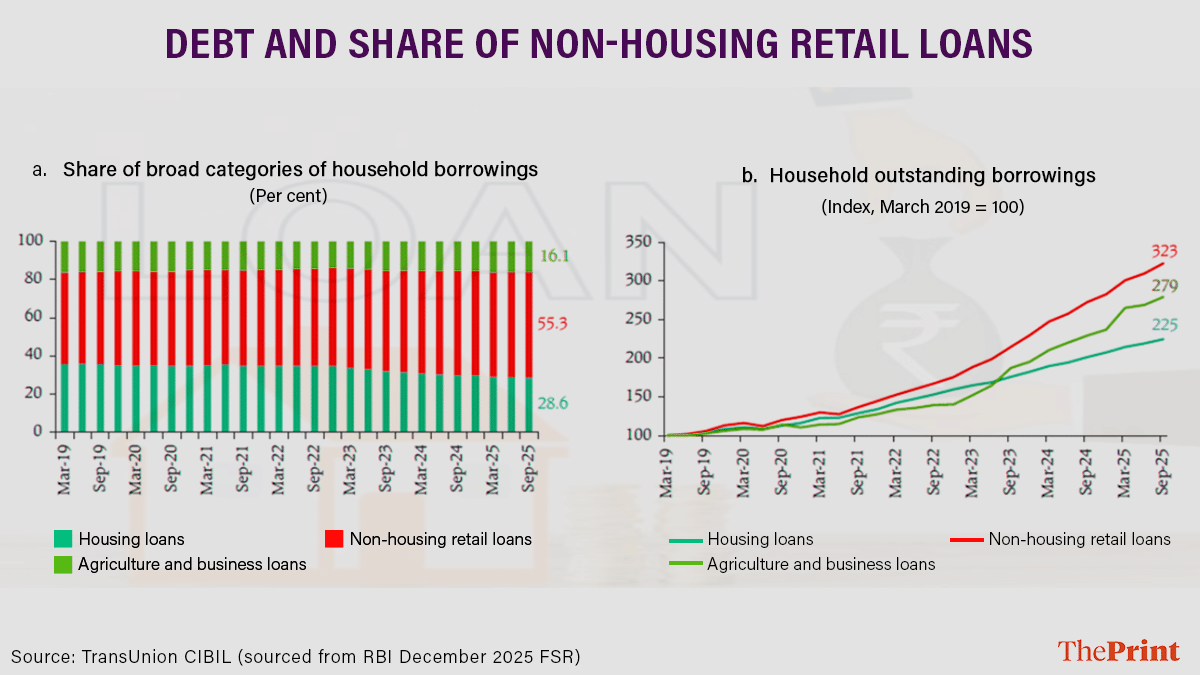

According to the report, retail credit ex-mortgage – or loans taken by households, excluding for property (or mortgages) – trebled since March 2019. An increasing share of these loans, data shows, was used to fund consumption, instead of financing productive assets.

Non-housing retail loans also accounted for more than half of all loans availed by households in the last fiscal year.

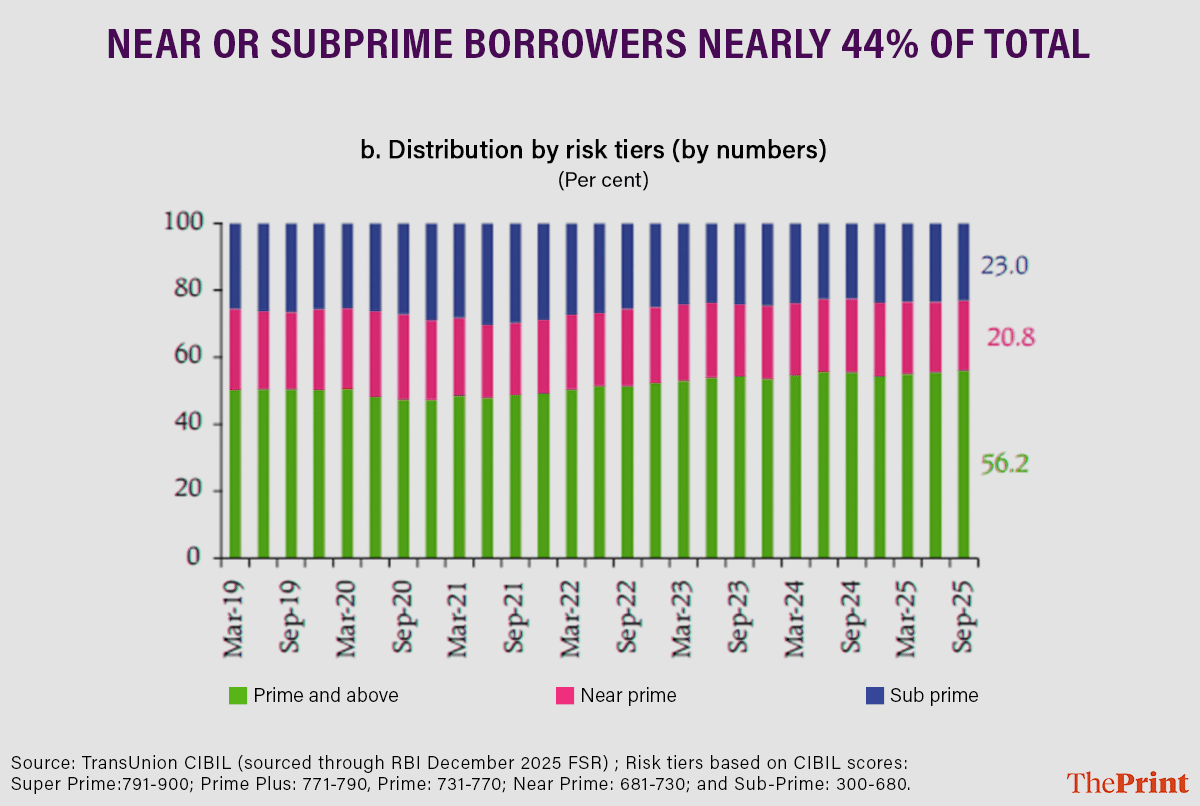

The trend, which continued into FY26, has another wrinkle in it. The percentage of near or subprime loans – to borrowers with low credit scores – was 44 percent, indicating poorer financial health.

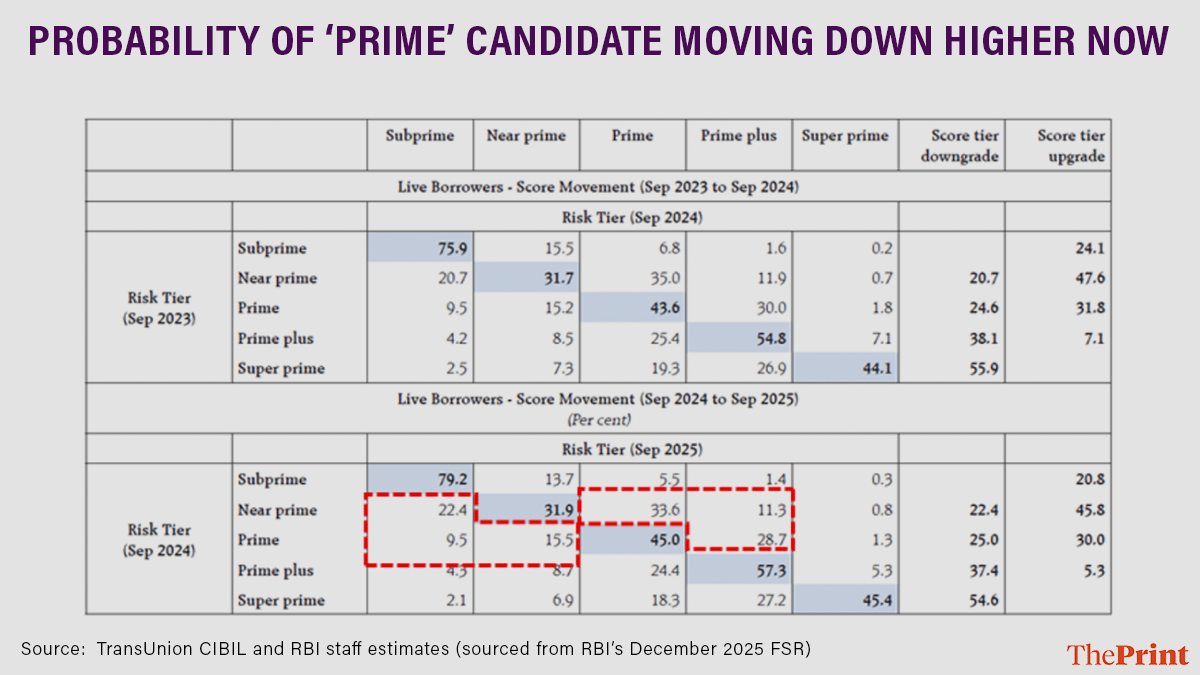

The RBI also included a transition matrix for different classes of borrowers (i.e., the probability of a prime customer going to near-prime, subprime, or to prime-plus and super-prime). What this shows is that the probability of credit scores deteriorating is increasing.

- Stressed lenders

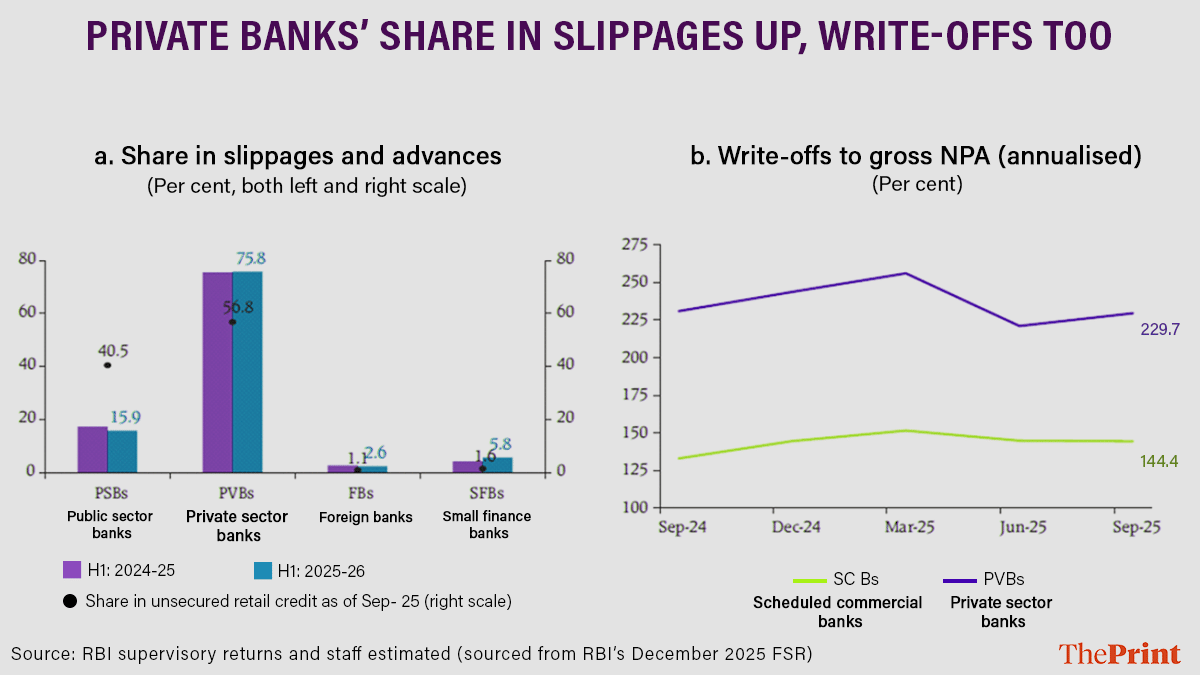

Currently, India’s banks and non-bank lenders (NBFCs) have good asset quality, but the banking sector has seen a rising share of slippages from March 2025 to September 2025. Further, for private banks, the percentage of loan write-offs to gross non-performing assets (GNPAs) increased too.

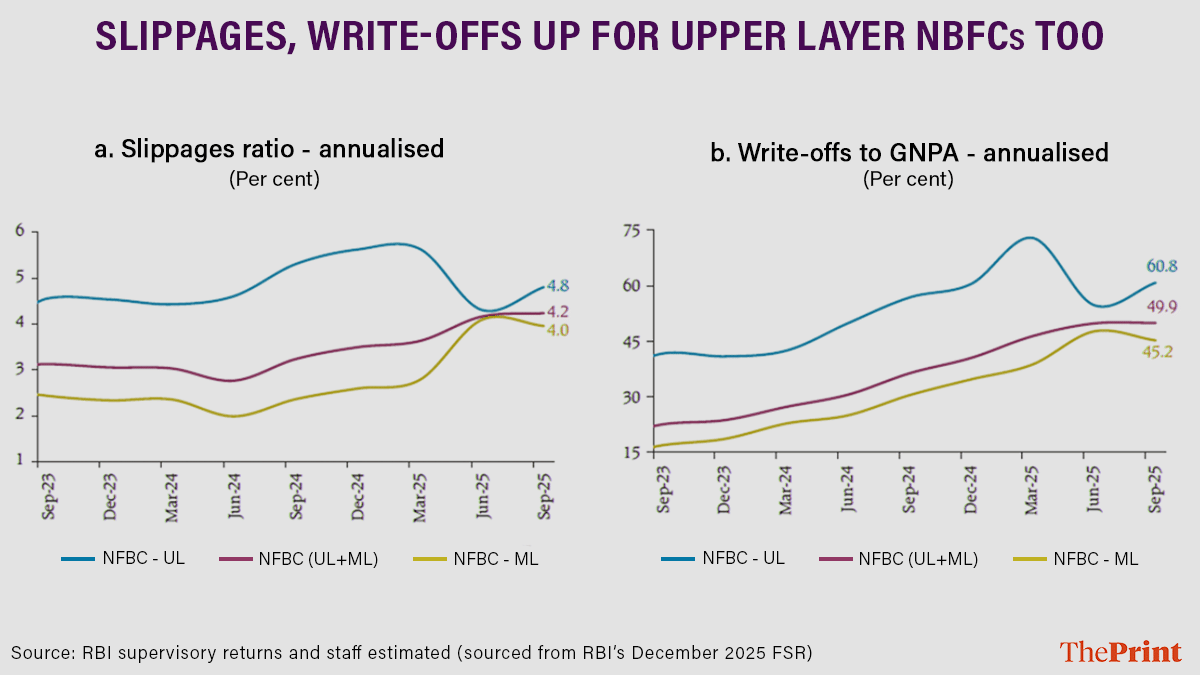

The same trend can be seen among NBFCs—rising slippages as well as a rising ratio of write-offs to GNPAs, indicating high stress levels.

Explaining the why

This deterioration may be attributed to three key issues.

- Jobs & wages aren’t increasing fast enough

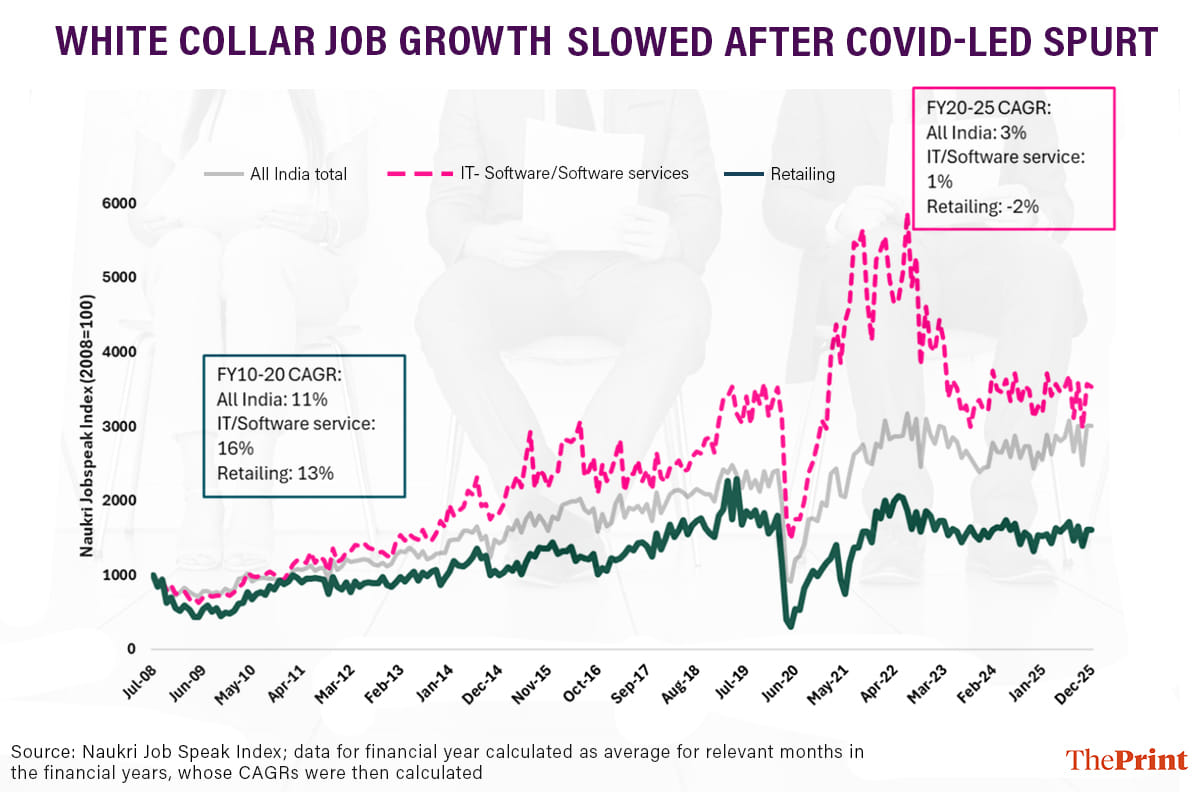

A major metric for job growth analysis is white collar jobs because these typically concern the middle class Indian who has historically driven consumption, and by extension, growth.

According to Naukri (India’s largest online classifieds business) JobSpeak index, job growth across all sectors was 11 percent per annum from FY10-20. After the pandemic (FY23-FY25), this rate slowed down to a mere 3 percent per annum.

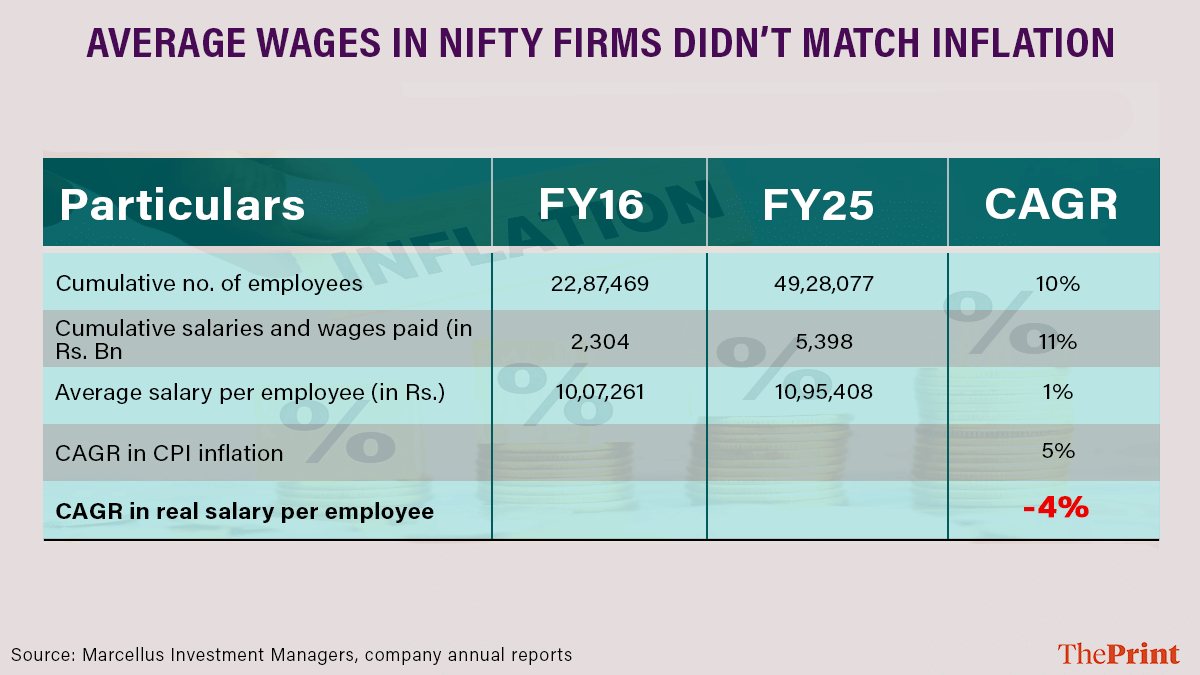

An analysis of Nifty companies (i.e., the largest companies in India by market capitalisation) also showed that salaries declined in real terms (i.e., adjusting for inflation) in the last nine years.

- Cost of living

Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation is a broadly used measure to understand the pace of rise in general prices for consumers. This indicator suggests that prices have been rising at a rate of 5-6 percent annually in the last ten years.

But, the official CPI estimation process uses a basket of goods that have little or no resemblance with the middle class’s actual consumption pattern. For instance, half of the CPI basket consists of food – though one will be hard-pressed to find a middle-class Indian family that spends half of its income on food.

A study of goods and services that the middle class purchases indicates that the cost of living for urban middle class families is doubling in roughly eight years, implying that inflation is around 9 percent/annum as opposed to the 5–6 percent CPI estimate.

For instance, the cost of a typical vegetarian thali rose 11 percent per annum in the last five years. Transport and communication CPI rose approximately 5 percent per annum over the last six years. Outstanding education loans, considered a proxy to study the cost of secondary education, rose from Rs 65,300 crore in 2020 to Rs 1.29 lakh crore in 2024, registering a compound annual growth rate of nearly 19 percent per annum.

Combining such examples with nominal wages increasing just 1 percent suggests that the reduction in real wages is not 4 percent but a steeper 8 percent per annum. In simpler terms, it implies that real wages – or purchasing power – is halving every decade.

- The social media bubble

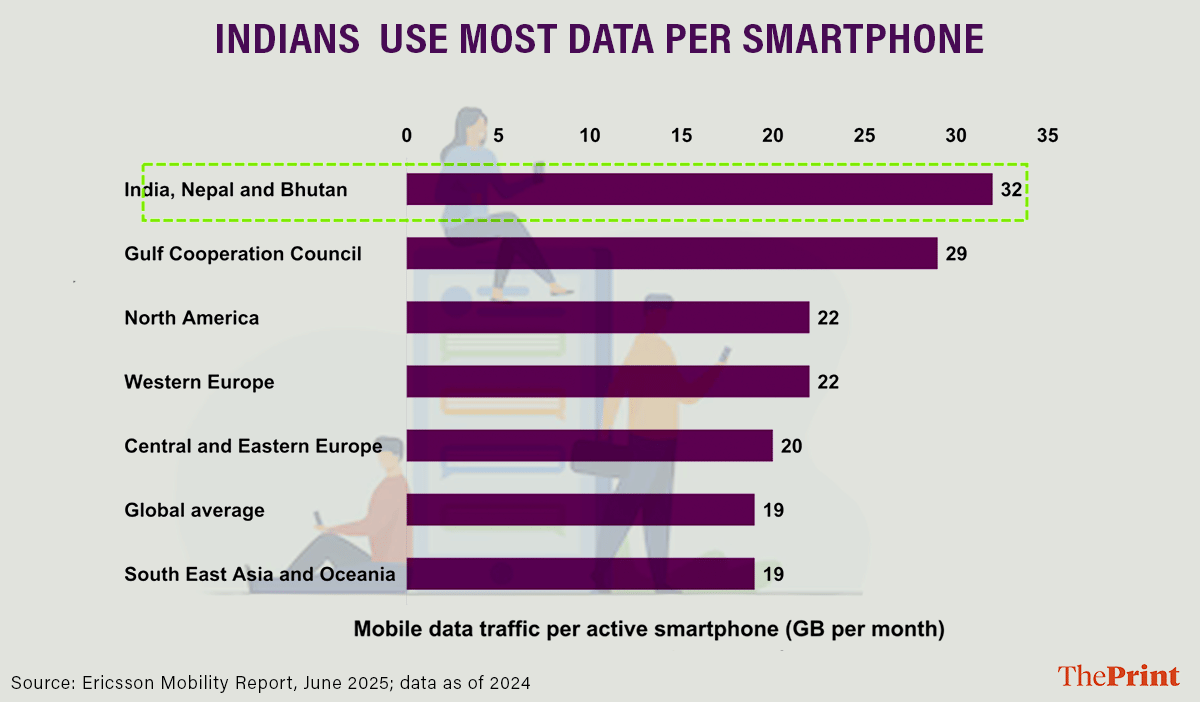

Rapid adoption of smartphones and Internet access across the country has meant that Indians today use more data per capita than their western counterparts.

A lot of people and businesses used online reach to their benefit, but there is a flipside too. Social media equalised the ability to aspire to something that most people could not even think of, let alone achieve.

A decade ago, a high net worth individual (HNI) vacationing in Maldives was only known to their close group of friends and acquaintances. This information was not in the public domain. But, now, because of widely accessible social media feeds, people working in, for instance, the underwriting department of an insurance company, can also see an HNI holidaying in the Maldives, and naturally aspire to live this life.

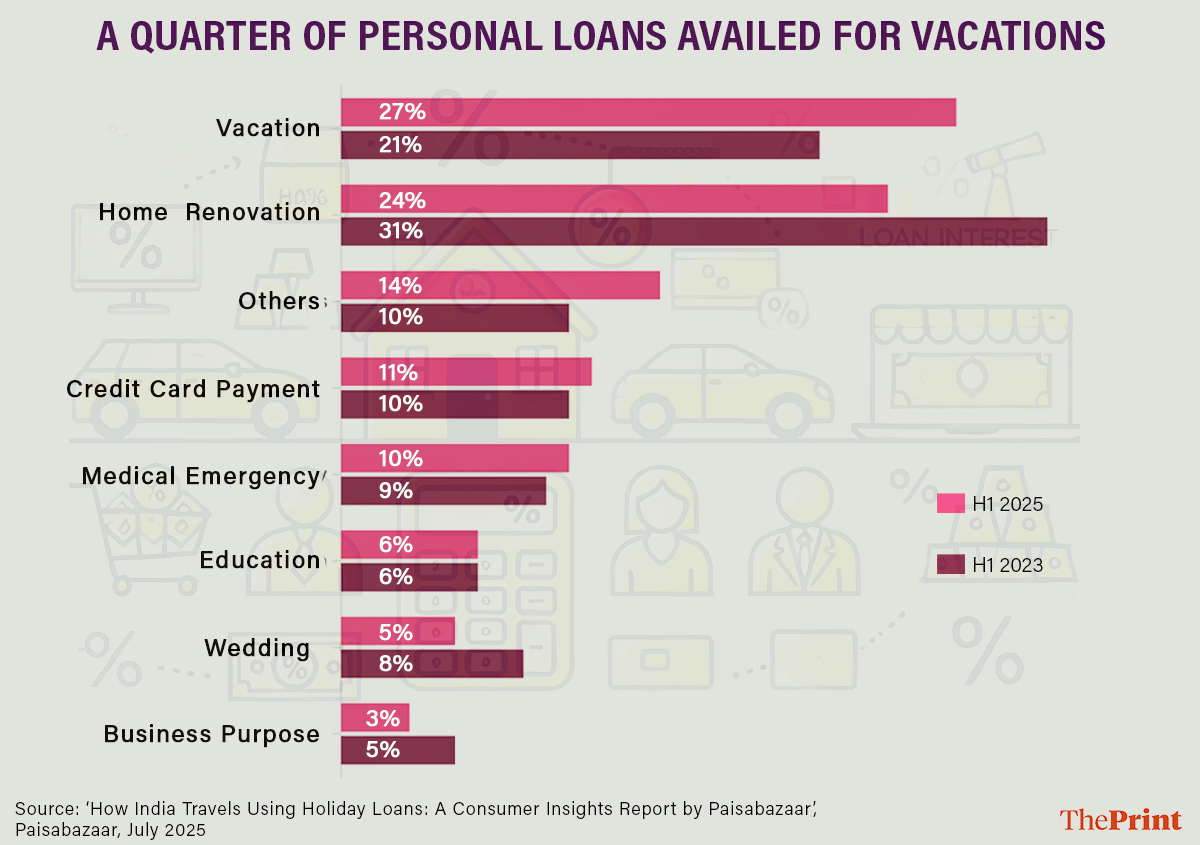

So, even if a person cannot afford such a vacation, one borrows money to finance this holiday. This behavioural change explains why the most common use of unsecured loans in India is “vacationing”, with more than a quarter of those loans being used to fund holidays.

What is the way out?

These problems are likely here to stay. As the country heads into a more uncertain job market amid global and technological headwinds, households may need to pare down debts and save more to cope with the new realities. As with everything else in life, this is achievable if properly planned.

Saurabh Mukherjea and Nandita Rajhansa work for Marcellus Investment Managers

(www.marcellus.in). The views and opinions expressed in this material are those of

the writers/authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy.

Also Read: Economic Survey 2025-26: The top 10 takeaways for India