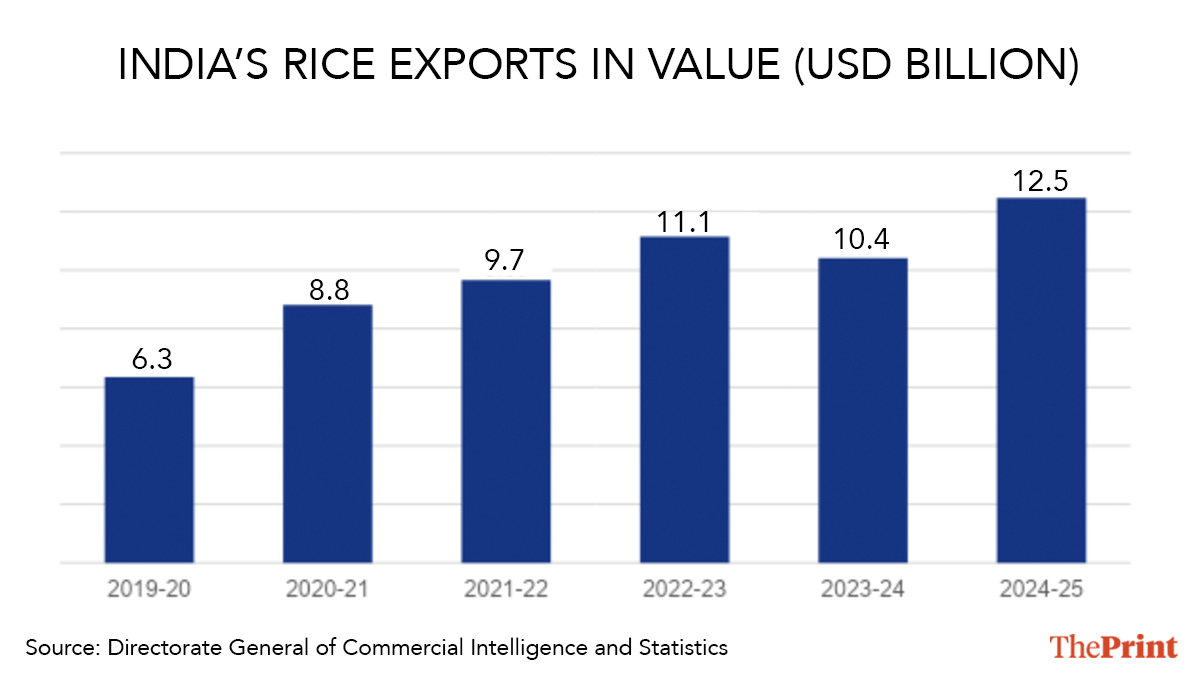

New Delhi: India, the world’s largest rice exporter, is poised to break its own record for rice exports in 2025-26, driven by a surge in domestic production, a sharp recovery in shipments, and new efforts to tap underserved export markets, an industry body told ThePrint.

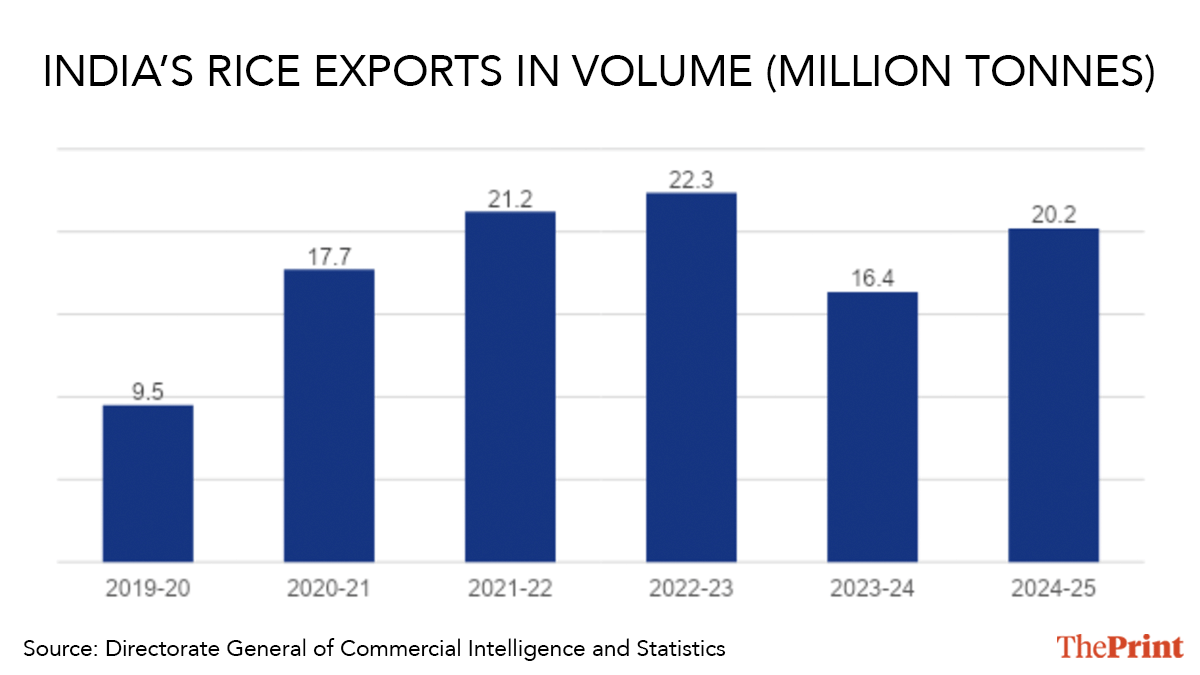

According to the Indian Rice Exporters Federation (IREF), exports of both basmati and non-basmati rice are expected to jump 16 percent to 23.5 million tonnes from 20.2 million tonnes in 2024-25.

Export volumes are expected to cross the previous high of 22.35 million tonnes in 2022-23, marking a turnaround from the slump of 2023-24, when rice exports fell to 16.35 million tonnes after government-imposed trade restrictions on certain varieties of non-basmati rice to safeguard domestic supplies amid soaring global prices.

However, once the restrictions were lifted last year, exports surged once again, growing 23.4 percent to 20.2 million tonnes in 2024-25, according to data from the Directorate General of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics (DGCIS), a government organisation responsible for compiling India’s trade statistics and commercial information.

Exporters believe this momentum will continue and potentially push exports to 30 million tonnes by 2026-27, a level India has never seen before.

“In the current fiscal year, rice exports are likely to grow by 16 percent, and we are targeting to export 30 million tonnes of rice in 2026-27,” IREF vice president Dev Garg told ThePrint.

IREF is a national body representing over 7,500 rice exporters across India.

Garg’s projections closely mirror the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates for November 2025, which peg India’s rice exports at around 25 million tonnes for the marketing year 2025-26.

USDA follows an October-September marketing year, while India follows an April-March fiscal year.

As of 2024-25, non-basmati accounted for 70 percent of total export volumes and 48 percent of value. Basmati is a premium, long-grain aromatic rice, whereas non-basmati is shorter and non-aromatic.

Data shows that India’s export market for basmati and non-basmati rice differs. While Africa and Asian countries are key markets for non-basmati rice, basmati exports are concentrated in the Middle East, Europe and North America.

In 2024-25, the five export markets for non-basmati – Benin, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Togo and Bangladesh – made up 44 percent of non-basmati export volumes, and 43.8 percent of value.

For basmati, the top five markets – Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Yemen and the United Arab Emirates – accounted for 61.2 percent of basmati export volumes and 59.3 percent of value.

Also Read: Why New Delhi seems ‘deluded’ about Trump’s tariffs & India returns to the global rice market

India surpasses China

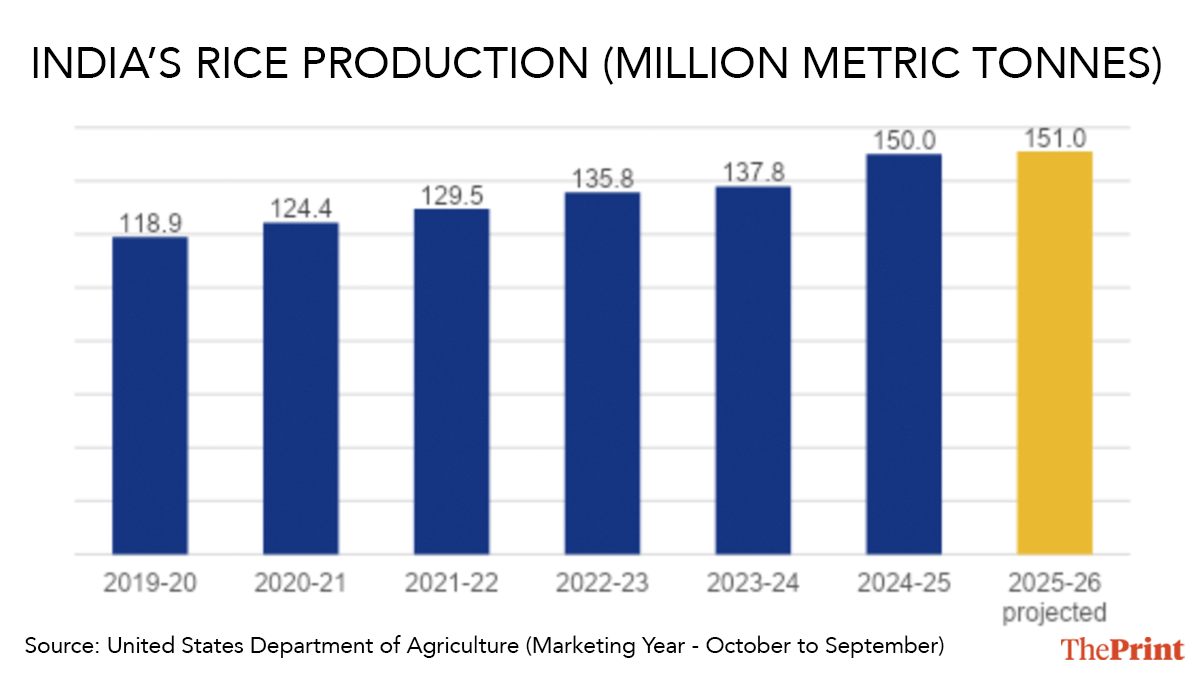

In 2024-25, India surpassed China to become the world’s largest rice producer, with output touching 150 million tonnes, roughly 28 percent of global production, according to USDA estimates.

Garg attributed this rise to factors like government incentives and improved agricultural practices. “Rice cultivation in India is a very lucrative business for farmers due to the availability of subsidies and minimum support price (MSP) by the government,” he said.

MSP is a price set by the government to guarantee farmers a minimum income for their crops, thereby protecting them from market volatility.

While the MSP for paddy was set at Rs 23.69 a kg this year, providing farmers a guaranteed return and insulating them from any volatility, Garg said that many states offered bonuses over and above this rate.

“While all states offer a premium over MSP, some states like Chhattisgarh offer a high premium of Rs 9 per kg,” he added.

Agricultural economist Ashok Gulati, professor at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), agreed that government incentives had driven the surge in rice production, but warned that India is now growing more rice than its ecology can sustain.

He noted that producing just one kg of rice requires 3,000-4,000 litres of water, making paddy one of the most water-intensive crops, while many regions in the country face depleted groundwater levels.

“India is a water-scarce country; it cannot afford millions of litres of water going into rice cultivation, especially with so many subsidies,” Gulati told ThePrint.

“Free power, water and subsidised fertilisers are prompting farmers to overproduce rice, and that’s hurting India’s ecological balance,” he added.

Former agriculture secretary Siraj Hussain told ThePrint that India must diversify its crop production from rice and wheat. “Paddy cultivation is more remunerative than other crops, thus farmers prefer it, but more incentives must be directed towards protein-rich crops like pulses,” he said.

Tapping underserved markets

Despite being the world’s largest rice exporter with shipments to more than 172 countries and a 38 percent share in global exports, Garg said India still has room to expand.

At the inaugural Bharat International Rice Conference (BIRC) held last month, IREF identified 26 countries where India’s penetration is low but have strong potential. They include Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Iraq, Japan and Mexico.

Collectively, these 26 markets import rice worth $20.1 billion (Rs. 1.8 lakh crore) . If India can capture a fraction of this share, it would help achieve the export target of 30 million tonnes by 2027, Garg added.

India’s share of rice exports to the Philippines is just 4 percent; the rest are with other suppliers or countries. “The target is to increase this share to 30 percent by the next fiscal year,” Garg said.

To capture these markets, IREF is mapping cuisine-specific preferences and identifying Indian rice varieties that can substitute those offered by competitors.

“We have identified Indian rice varieties that are most suitable with the cuisine of that country, so that we can offer them a like-for-like replacement,” Garg added.

Growing production capacity

According to the USDA, India produced 150 million tonnes of rice across 51.4 million hectares in 2024-25, up 9 percent from the previous year’s 137.8 million tonnes.

Telangana leads India’s rice production with 16.87 million tonnes on 4.69 million hectares, according to IREF. It is followed by West Bengal with 15.75 million tonnes, and Uttar Pradesh with 12.5 million tonnes.

While acreage has expanded gradually, India’s milled yield has also improved slowly from 2.4 tonnes per hectare in 2015-16 to 2.92 tonnes in 2024-25, USDA data shows. However, India trails China, which has a milled yield of 5.01 tonnes per hectare.

A.K. Singh, director of the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), said that instead of cutting rice production due to surplus, India should adopt more climate-resilient techniques like Direct Seeded Rice (DSR) to enhance yield and save water.

In DSR, seeds are sown directly into the field, instead of the traditional practice of transplanting seedlings to flooded fields.

“DSR can cut water use and greenhouse gas emissions by about 35 percent, while lowering cultivation costs by Rs 3,000-5,000 per acre,” Singh told ThePrint.

Flip side of production boom

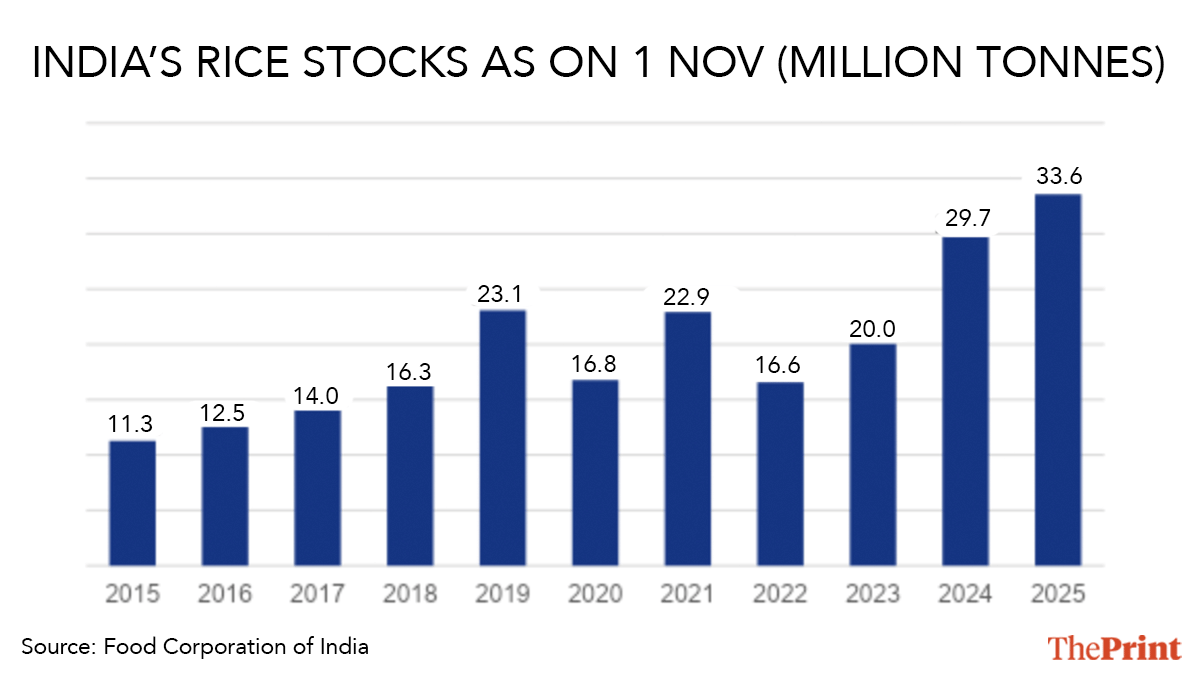

India’s rice production boom has created a challenge of massive surplus stocks in government warehouses. In November 2025, the Food Corporation of India (FCI) was sitting on 33.59 million tonnes of rice – the highest in a decade for the month and more than three times the government’s buffer norm of 10.25 million tonnes.

The FCI is a government-owned agency that manages India’s food security through procuring, storing and distributing food grains.

“Rice stocks being three times the buffer levels show mismanagement by the government and FCI,” Gulati said.

He added that the FCI’s economic costs – which include procurement, incidentals, storing and distribution – comes to Rs 42 per kg. But if the rice is sold in auctions or used for making ethanol, this cost is not recovered.

But Singh offered a counterpoint to concerns about surplus stocks, saying they were vital for national food security in India where domestic rice consumption is more than 100 million tonnes annually.

“A single year of drought in India can cut the production by 15 to 20 million tonnes,” he said.

Rice is also important for many state and central government welfare schemes, he said, adding that a surplus helps in meeting demand during unforeseen events.

According to IREF, a major welfare scheme is the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY), which provides 5 kg of free grain to 810 million people and uses 36-38 million tonnes of rice a year. The scheme has been extended until 2028.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: Global rice prices drop after India allows white rice exports

It’s great how much rice we can generate but the reality is that we are still producing less than we can. Most farmers don’t adapt to new techniques for various reasons.

Some do. Some farmers actually switch to cash crops depending on the local demand. I have seen farmers growing avocados in this country which is great and very smart. Hopefully everyone thinks about how they can make more money and not depend on government subsidies.