This report is the second of a three-part series on recent Indian engagement in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region.

New Delhi: The US’ decision last month to ease some economic sanctions on Venezuela — home to the world’s largest crude oil reserves — presents an opportunity for Indian refiners, who have the capacity to refine heavy crude from the Latin American country. It can also help India diversify its crude import basket further, given that it has also stopped importing crude from another sanctioned country, Iran, since 2019.

Yet, it will be a while before Venezuela’s state-owned oil giant, Petróleos de Venezuela (PdVSA), returns to its historic levels of 3 million barrels per day (bpd) in the pre-sanction period as its infrastructure is outdated and requires “substantial” investment to be upgraded.

Much also hinges on how fair the 2024 Venezuelan presidential elections pan out, since that is the basis on which incumbent President Nicolás Maduro was able to strike a deal with the Americans.

The opportunity for Indian refiners aside, New Delhi is already in a “sweet spot” after enjoying cheap Russian oil for months on end, said R. Viswanathan, a former Indian ambassador to Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay and Venezuela.

Thanks to the G7 countries’ (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK and US) price cap on Russian oil, Indian importers have grabbed oil under $60 per barrel.

India, the world’s third largest oil importer, has also become a unique player as its refineries have resold refined Russian crude to European and US markets this year.

“Recent comments from External Affairs Minister Dr S. Jaishankar and Minister of Oil and Petroleum Hardeep Singh Puri reflect just how comfortable we are in this regard,” Viswanathan told ThePrint.

Jaishankar this month said India is “waiting for a thank you” from the world after its strategic oil purchases helped to reduce prices, meet countries’ energy demands and perhaps even out global inflation. Earlier, Puri had said that India would “buy from wherever oil is cheap”, noting that Indian Oil Corporation (IOC) and Reliance Industries (RIL) have bought Venezuelan oil in the past.

An industry leader, previously associated with RIL, told ThePrint that Indian refineries in Jamnagar, Barauni and other areas welcomed the easing of US sanctions on Venezuela, which has long been reeling under a socioeconomic and political crisis.

“Refineries in Jamnagar can refine the crudest of crude oil, so there’s definitely an opportunity there,” the industry leader said. Unlike Russian Urals, Venezuelan crude has high sulphur content and is harder to refine.

In 2017 and for some years prior to that, RIL’s gross refining margin (GRM) beat the Singapore oil benchmark which, according to the industry source, happened at a time when Indian oil firms had a “buffet” of oil sources to choose from, i.e. Venezuela, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia.

Gross refining margin is what a company earns from turning every barrel of crude oil into fuel.

India’s crude basket changed after US sanctions on Venezuela and Iran. After the Ukraine war began, Russia became India’s prime source. The rupee trade with Moscow has been a boon, too, industry sources said.

Russia is currently the top oil supplier to India, reported to be averaging 1.76 million bpd from April to September this year, followed by Iraq and Saudi Arabia.

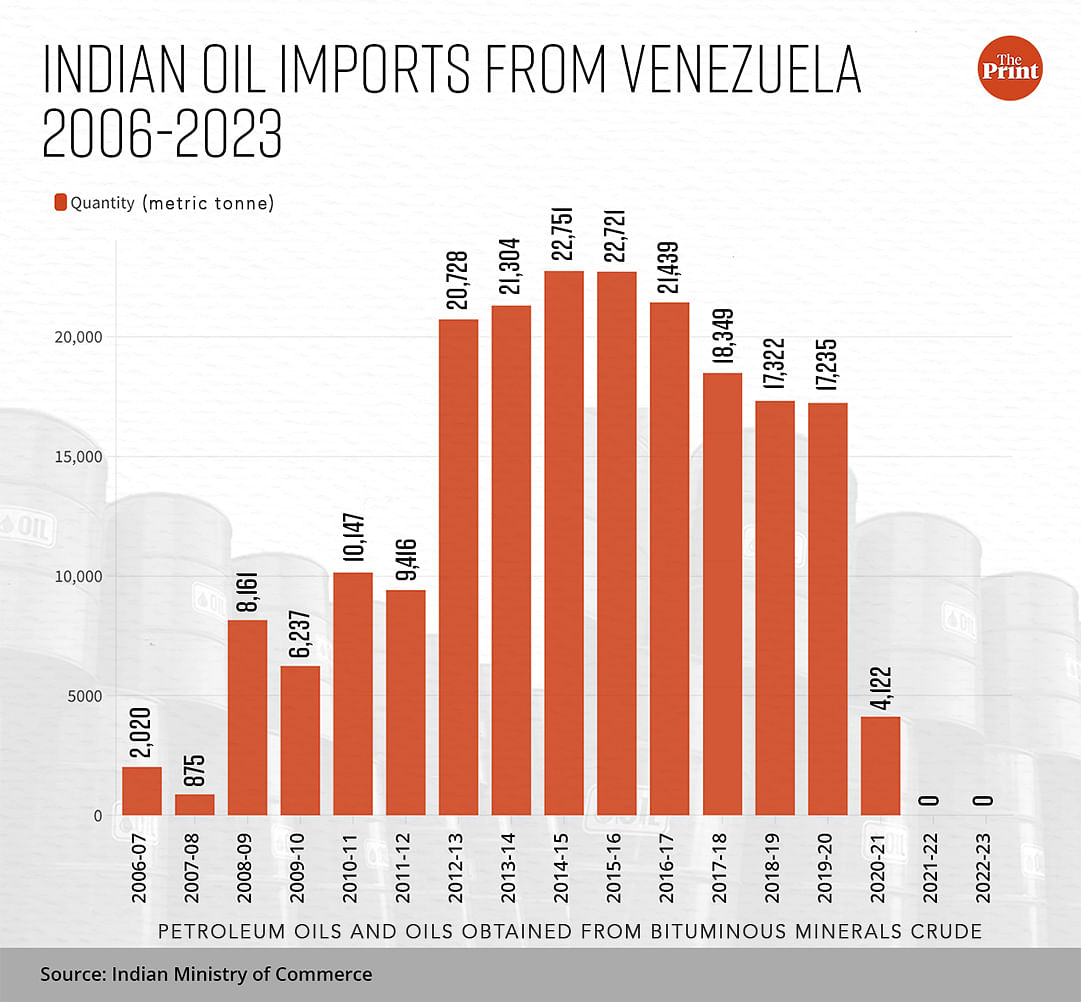

India has gradually reduced oil imports from Venezuela after the US slapped sanctions on the Latin American country in 2017 and tightened them in 2019.

Also Read: How India is boosting its strategic & economic ties with distant Latin America, Caribbean

Indian oil imports pre-sanction & failure of joint ventures

Before the US imposed sanctions on Venezuela in 2017 and 2019, India consistently bought crude from the Latin American country.

The upward trend began in 2012, when India overtook China as the largest Asian buyer of Venezuelan crude. The Latin American country was the third largest supplier of crude to India that year. The peak was in 2014-2015 when India imported over 22,000 tonnes of Venezuelan crude, according to data from the Indian commerce ministry.

In 2013-2014, many Indian firms were keen to ramp up imports. A document from the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) shows that RIL, which had been importing about 300,000 bpd of Venezuela oil, intended to increase it to 400,000 bpd. This was a couple of years after RIL signed a 15-year heavy crude oil supply contract with PdVSA.

There was much excitement from the IOC, too, around 2014. It wanted to import 1.5 million tonnes for its then-commissioned Paradip refinery, which would later start operations in 2016. HMEL — a public-private joint venture between Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited (HPCL) and Mittal Energy Investments — also wanted to import two million tonnes of oil from the Latin American country for processing at its Bhatinda refinery in Punjab, the MEA document shows.

According to Smita Purushottam, who served as ambassador to Venezuela from 2012 to 2015, a rupee payment mechanism featuring “oil for goods” — similar to what the Chinese had in place until 2019 — was floated to the MEA during her tenure.

“Indian exporters, especially in pharma, were highly frustrated with payment delays from Venezuela. It was also clear that Venezuela needed many Indian consumer goods and infrastructure like pumps produced by Kirloskar Brothers,” she said.

In 2015, she floated a proposal for an oil-for-goods agreement to the MEA. The MEA “enthusiastically” supported the proposal but the Venezuelans were “extremely cool”, recalled the former diplomat. “I suspect they didn’t want to disrupt the steady flow of dollar-trade from Indian oil firms,” she said.

Purushottam served during the eras of strongmen leaders in Venezuela — Hugo Chávez (1999 to 2013) and current President Maduro. “Both contributed to the crash of the economy,” she recalled, creating a “petro-narco” state for many years.

“Petro-narco state” refers to a government that gains revenue from petroleum and the drug trade. In the past, Maduro has faced allegations of drug trafficking, including conspiring with a Colombian guerrilla group to flood the US with cocaine.

Indian firms had in the early 2010s explored strategic investments in oil-rich Venezuela. In 2013, PdVSA and India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) signed a deal for oil field exploration in Venezuela’s Faja area.

But joint ventures eventually fell by the wayside.

Take the San Cristobal oil field project, in which ONGC Videsh had a 40 percent stake and PdVSA a 60 percent stake. It was hit by a payment crisis and in 2018, it was reported that PdVSA had not paid dividends to the Indian firm for many years, racking up a debt of approximately $56 million. The project had to be redeveloped to liquidate ONGC’s outstanding dividends.

As the geopolitical landscape shifts, India’s oil imports from various countries, including Venezuela, are likely to be influenced by the ongoing sanctions and market dynamics.

New Delhi will be “wary” of any such joint ventures in the future, even if more American sanctions on Venezuela are lifted, said Viswanathan.

“A lot hinges on the 2024 Venezuelan elections and whether they are free and fair. Even in the event of more American sanctions being lifted, Indian firms would not jump at strategic investments as they did in the past, but trade in oil would be on the table,” he told ThePrint.

Oil as collateral

Caracas may have shown no interest in Puroshottam’s proposal but the Venezuelan government had no such issues with such agreements with Beijing or Moscow.

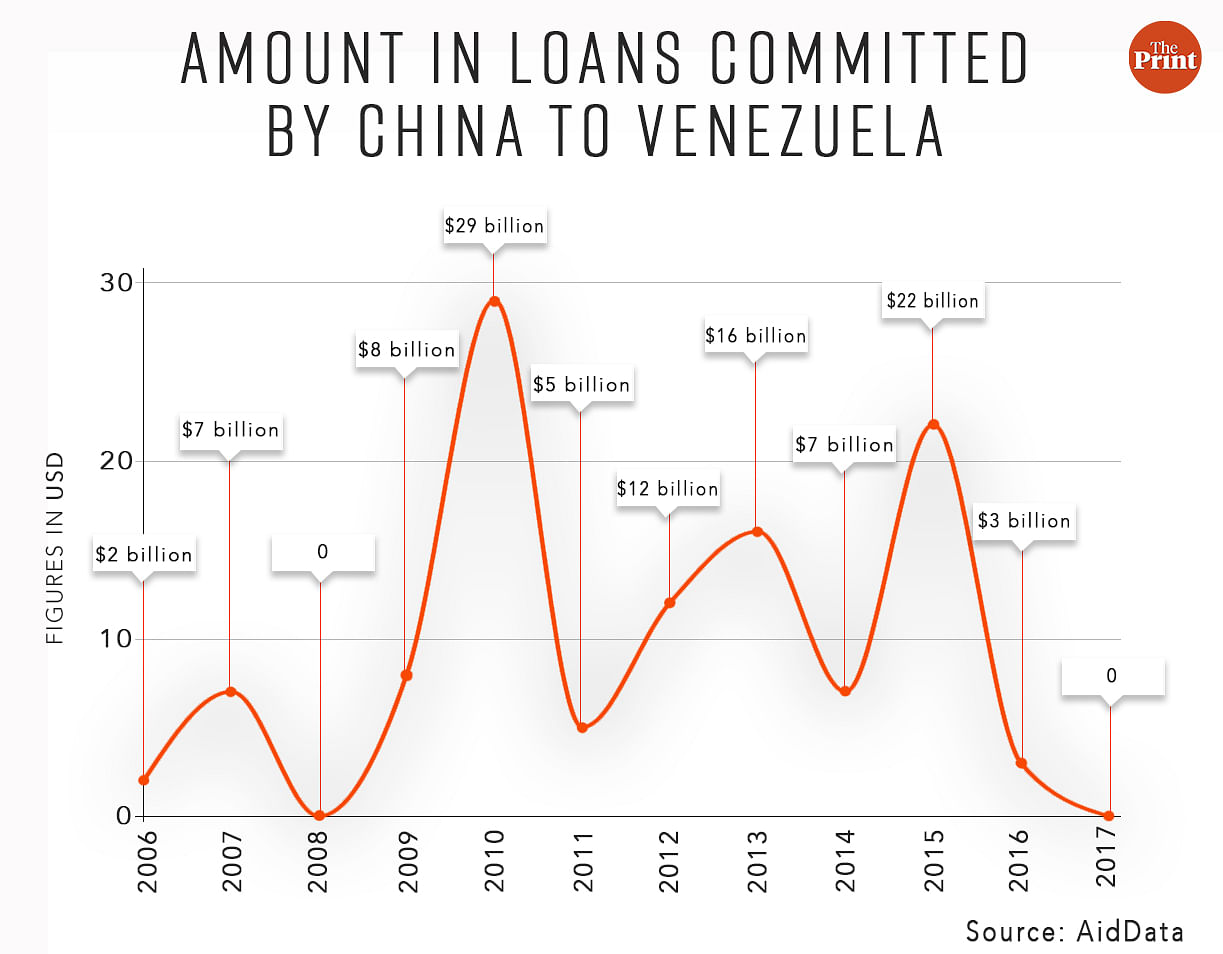

Venezuela is the second largest country to receive financial commitments from China between the years 2000 and 2021. This period saw at least $113 billion lent to Venezuela through various means for different purposes, as reported by AidData, a research lab part of the College of William and Mary in the US.

The vast majority of the sums were lent between 2006 and 2016, with the highest commitments made in 2010 ($29 billion) and 2015 ($22 billion). In many cases, petroleum sales and purchase contracts were signed between PdVSA and China National United Oil Corporation (ChinaOil) based on a pre-agreed pricing formula and pre-approved quantity until the full repayment of all amounts due, AidData noted.

For example, on 6 November, 2007, a six-party framework agreement for the establishment of Joint China-Venezuela Fund (JCVF) was signed to govern three other deals: a four-party agreement between China Development Bank (CDB), Banco de Desarrollo Económico y Social de Venezuela (BANDES), ChinaOil and PdVSA; an oil-backed, $4 billion loan (facility) agreement between BANDES and CDB; and the Petroleum Sales and Purchase Contract between PdVSA and ChinaOil, according to AidData.

Under the third agreement, the PdVSA agreed to sell 100,000 barrels of fuel and/or crude oil per day to ChinaOil until the full repayment of all amounts due in connection with the second agreement.

In parallel to the JCVF, the CDB and BANDES signed a $20.3 billion oil-backed loan agreement known as the Long-Term Facility Agreement on 16 September, 2010. The facility consisted of two tranches — a yuan 70 billion tranche and a $10 billion tranche — a dual currency agreement, AidData noted.

The two tranches were fully disbursed in 2010 and 2011. By 2016, Venezuela had about $9.3 billion outstanding on the $20.3 billion agreement. PdVSA agreed to sell 2,00,000-3,00,000 barrels of fuel per day at a pre-agreed price with ChinaOil on behalf of the Venezuelan government until the full repayment on this agreement was made, AidData found.

However, by 2019, ChinaOil reportedly stopped buying oil from PdVSA directly due to the US sanctions on Caracas.

After 2016, no new loan commitments, backed by Venezuelan oil, were made by China.

According to Viswanathan, Venezuela was pushed into the “waiting arms” of the Chinese due to American policy.

“The US prohibited access to Caracas to western capital markets. This left the country (Venezuela) bereft of international funding and Beijing stepped in to lend to Venezuela. However, they were careful in ensuring minimal direct investment in the nation,” Viswanathan said.

“China has no interest in provoking the US by contravening the sanctions placed on Venezuela. There is no reason for Beijing to pick this fight (with the US),” Viswanathan added, explaining why ChinaOil stopped carrying Venezuelan oil from 2019.

While ChinaOil does not officially carry Venezuelan crude, nevertheless, oil from the country finds a way to Chinese shores — rebranded as “Malaysian” oil for example, a Reuters investigation found last year.

Since 2020, China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC) has been carrying Venezuelan crude on three oil tankers — Xingye, Yongle and Thousand Sunny — worth roughly $1.5 billion, according to the investigation.

CASIC — the state-owned enterprise that specialises in defence and space technology — ships the crude from the Jose port in Venezuela. It reaches the Chinese coastal city of Ningbo (south of Shanghai) and is then eventually sent on to independent refineries in China.

Fortune favours the bold

In October 2013, Venezuela reported a total production of 2.8 million bpd to the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), while in October 2023, it reported a total of 7,86,000 bpd — a quarter of its total production a decade ago.

Venezuelan oil investment and production through PDVSA gradually began to fall in the 2010s, was accentuated by American sanctions in mid-2017 and then with an embargo on Venezuelan oil in early 2019.

Today, Venezuela holds 17.5 per cent of the world’s oil reserves but is responsible only for 0.8 per cent of production, according to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

Speaking to ThePrint, Carlos de Miguel from ECLAC’s Natural Resources Division said Venezuela’s increased crude oil production is not expected to have a major impact on the world market in the short term.

Though there may be a small increase in hydrocarbon production, this does not mean that the historic levels of 3 million bpd of the late 2010s will be reached, he said.

“Substantial investments are required (for PdVSA) to overhaul or upgrade its infrastructure,” he added.

This was echoed by Viswanathan, who said American sanctions disadvantaged the PdVSA when it came to purchasing spare parts to maintain its production facilities, thereby reducing its daily output.

“Venezuela has been unable to maintain its production facilities or purchase the spares required for the maintenance of these units. This is because of the effects of American sanctions on the country,” Viswanathan said.

He added: “If sanctions are lifted, Venezuela would be able to purchase the necessary parts and start pumping out production to previously seen amounts. The production of oil can flourish with the easing of sanctions.”

If that is indeed the case, apart from India waiting in the wings, Beijing would also look to profit from the easing of sanctions. As Standard & Poor Global reports, ChinaOil is preparing to re-enter the Venezuelan markets.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: ‘Hope to see India benefiting from Russian oil price cap,’ says US Treasury Secy Janet Yellen