New Delhi: Can India unilaterally keep the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in abeyance? According to experts, it can.

Senior advocate Mohan V. Katarki, an expert on transboundary water disputes, told ThePrint that the treaty does not have a provision to keep it “in abeyance”.

“It does not permit, but it does not prohibit, also. With no prohibition imposed on the parties from keeping the treaty in abeyance, general international law governs them (the parties),” he explained.

India announced late Wednesday night that the treaty will be held in abeyance with immediate effect “until Pakistan credibly and irrevocably abjures its support for cross-border terrorism”.

The move came a day after the Pahalgam terror attack that left at least 26 people, including tourists, dead on Tuesday when four Lashkar-e-Taiba terrorists opened fire in a popular tourist spot in the district.

The 1960 treaty was brokered by the World Bank between India and Pakistan, covering the use of the rivers in the Indus Basin. It allows India “unrestricted use” of Ravi, Beas and Sutlej, the three eastern rivers in the Indus basin, and similar rights to Pakistan over the Indus, Jhelum and Chenab, the three western rivers.

Katarki pointed out that the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties governs the treaties signed after 1969, the year of the convention’s adoption. The convention has provisions regulating the right of withdrawal.

The Vienna Convention’s Article 4 clarifies that the convention applies only to treaties “concluded by States after entry into force of the convention”, he said.

“But, if the Vienna Convention does not cover a treaty, signed pre-1969, you have all the freedom,” he asserted.

Additionally, India is not a signatory to the Vienna Convention, whereas Pakistan has signed but not ratified it.

Also Read: Ka***e, Ku**e, hara****de—angry Owaisi denounces Pahalgam terrorists

‘Strategic ambiguity’

But what does abeyance mean, and how is it different from suspension?

Ridhish Rajvanshi, an international trade law expert, explained that usually, a suspension is a formal process, requiring a notification from the party suspending the treaty, even if done unilaterally.

“Abeyance, on the other hand, can be said to be the use of a party’s sovereign right to place the treaty in a suspended state or not execute its obligations under a treaty without a formal notification,” he told ThePrint.

In either case, Rajvanshi said the Indus Waters Treaty does not contain such provisions, and that within the contours of customary international law, India could keep it “in abeyance”.

As for termination, he explained, technically, there is no provision in the Indus Waters Treaty for unilateral termination or suspension.

He told ThePrint that under the treaty, “the IWT could be terminated by a ratified treaty concluded between the two governments for that purpose.”

London-based lawyer Dharminder Singh Kaleka explained that “suspension” and “abeyance” are different in “tone and in teeth”.

He explained that while suspension is a formal legal measure governed by international law, “abeyance, by contrast, is a tool of strategic ambiguity—it freezes the operational mechanics of the treaty without triggering its collapse”.

“In effect, India is saying: We have not torn the treaty up—but we are not playing by the old rules either, not until the rules of engagement with terrorism are rewritten by Pakistan,” Kaleka, a policy expert specialising in South Asian economies, geopolitics and development strategy, said.

What happens next?

What would be the impact if India kept the treaty in abeyance?

Katarki explained that keeping the treaty in abeyance might not affect Pakistan.

“Because water flows by gravity with or without a treaty. India has no dams to cut off water in the Indus or its tributaries, Jhelum and Chenab, known as the western rivers. Pakistan will continue to get what it has been getting,” he said.

But now, he added, India could freely plan to divert 5 million acre feet (MAF) of water from the western rivers Jhelum or Chenab to the eastern rivers Ravi, Beas, or Satluj.

“This will not affect Pakistan because about 20 MAF or more is going to sea in Pakistan as unused water,” he told ThePrint.

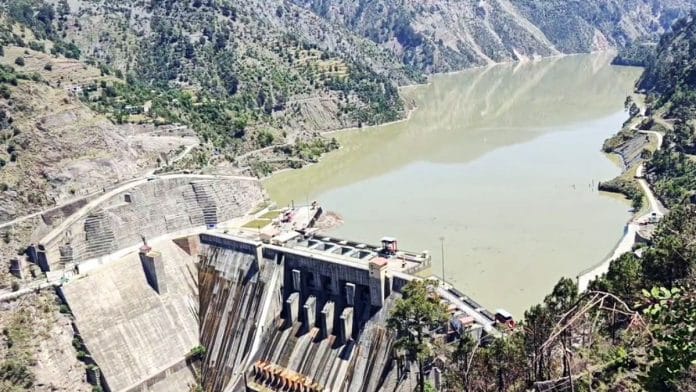

Kaleka also said that among the options available to India, the country could accelerate infrastructure on projects such as Kishanganga and Ratle. “These are not just dams—they are instruments of control, subtly redrawing the hydraulic map of South Asia,” he said.

Kaleka asserted that “abeyance is a necessary first step—a message of restraint, not retreat”.

“Until Pakistan takes credible and irreversible steps to dismantle terror networks operating across the border, there can be no return to technical cooperation. The Indus Waters Treaty is no longer just a water-sharing agreement. It is now a variable in India’s national security doctrine,” Kaleka explained.

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)