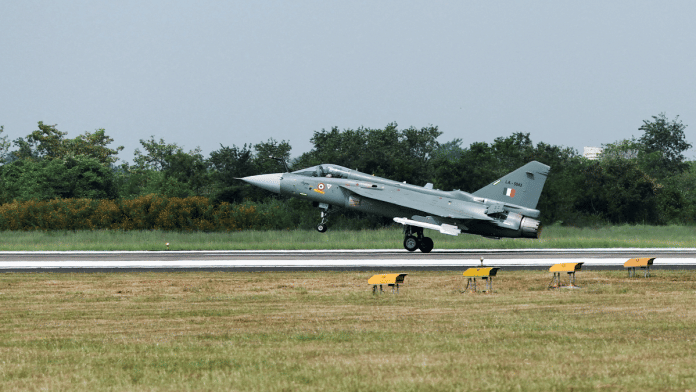

New Delhi: The crash of a Tejas Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) and the pilot’s death at the Dubai airshow less than a month ago has spotlighted the dangerous lives fighter pilots lead.

Any number of things can go wrong. While standard safety systems, which can interfere with flight acrobatics, are generally de-activated during airshows, it puts the focus on the need for sustained advances in safety mechanisms.

Aviators describe transitions from negative into positive Gs (G force) as the most dangerous of existing manoeuvres, where reaction time, decision-making and execution is affected immensely; it falls under the ambit of the A-LOC (almost loss of consciousness) syndrome.

The line starts to blur, almost literally, once a pilot has hit A-LOC, beyond which is the danger of G-LOC (G-Force induced loss of consciousness), which can last for over half a minute, during which the pilot is incapacitated and no one is in control of the jet. If the pilot fails to recover consciousness in time, the jet stalls and descends rapidly towards the ground resulting in Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT).

Between 2005 and 2024, CFITs accounted for nearly 5 percent of total accidents, but caused over 18 percent of all fatalities globally.

As per the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), CFIT occurs when a serviceable aircraft operated by qualified pilots is unintentionally flown into the ground, water, or an obstacle. Such accidents often occur without mechanical failures, typically stemming from pilot disorientation, navigational error, or inadequate terrain awareness.

Two safeguarding systems have been developed and tested as part of the Flight Control System (FCS) in the Quadruplex Digital Fly-by-Wire (FBW) system on the Tejas LCA. These enable the pilot to stick to combat controls, while the systems in place ensure no departure from the controlled flight path.

In 2020, the Tejas MK1 underwent auto low speed recovery (ALSR) and disorientation recovery function (DFR) trials for Final Operational Clearance (FOC). ALSR gets activated automatically, while the DFR is manually engaged.

ALSR activates—when it detects stalling or low speeds—by warning the pilot to take corrective action. A lack of response from the pilot triggers automated actions to prevent the plane from stalling, allowing the pilot to skirt the safety envelope and perform sharp manoeuvres.

The DFR is a manually activated panic button built in to return a plane to a stable trajectory, to prevent loss of control in case of spatial disorientation. Legacy systems like MiGs have also had older, less refined versions of such systems which might have laid the groundwork to incorporate them in the Tejas later.

A common misconception is that a pilot now has it easier compared to his predecessors. While the move from manual to computer-based FBW systems has enabled a safer and quicker flight, it also means manoeuvres at G-forces higher than ever before, establishing the need for more sophisticated technology and automated safety upgrades on the FCS.

The Americans operate the state-of-the-art and best in class systems called the auto GCAS (Ground Collision Avoidance System) and the auto ACAS (Air Collision Avoidance System) which were jointly developed by Lockheed, the Air Force Research Laboratory, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), on the F-16 Block 40/50s, F-22 Raptors and F-35.

The fully automated systems use terrain mapping and location vectors to determine imminent CFIT. The systems monitor the pilot and pilot inputs and consider a variety of variables including GPS, their own navigation system and digital terrain elevation data to arrive at the 3-D position relative to the earth’s surface.

This enables the systems to determine the time left for impact and the necessary evasive manoeuvre without any throttle input. According to reports. the Auto GCAS has a very low threshold so it can fly close to the ground, over mountains, down valleys, across desert floors or over the water.

As per Kim Sears of the New Media branch of American Forces Information Service, the programme differs from current crash-avoidance systems in that it doesn’t create nuisance warnings and activates only at the last moment to take control and recover the aircraft. The automatic action is taken only when aircraft is within 1.5 seconds of the point of no return and no action has been taken by the pilot.

Interestingly, the development of Auto GCAS had Swedish input, as Saab was developing it for the Gripen. An American delegation had gone to Linkoping once flight tests were complete to give an update on findings. Saab elected not to pursue the solution which eventually went into the F-16 and later F-35 and chose a slightly different Auto GCAS solution.

(Edited by Viny Mishra)

Also read: A tribute to Tejas. India’s delay culture is the real enemy in the skies