Presenting her ninth Union Budget on Sunday, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman proposed to spend about Rs 53.5 lakh crore in the upcoming year, which, for a population of about 1.48 billion, translates to around Rs 36,000 per person. Out of this annual budget, about 2.6 per cent (Rs 1.4 lakh crore) is earmarked for the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. This share has been falling in recent years. In this article, we review the announcements related to the agriculture and allied sectors.

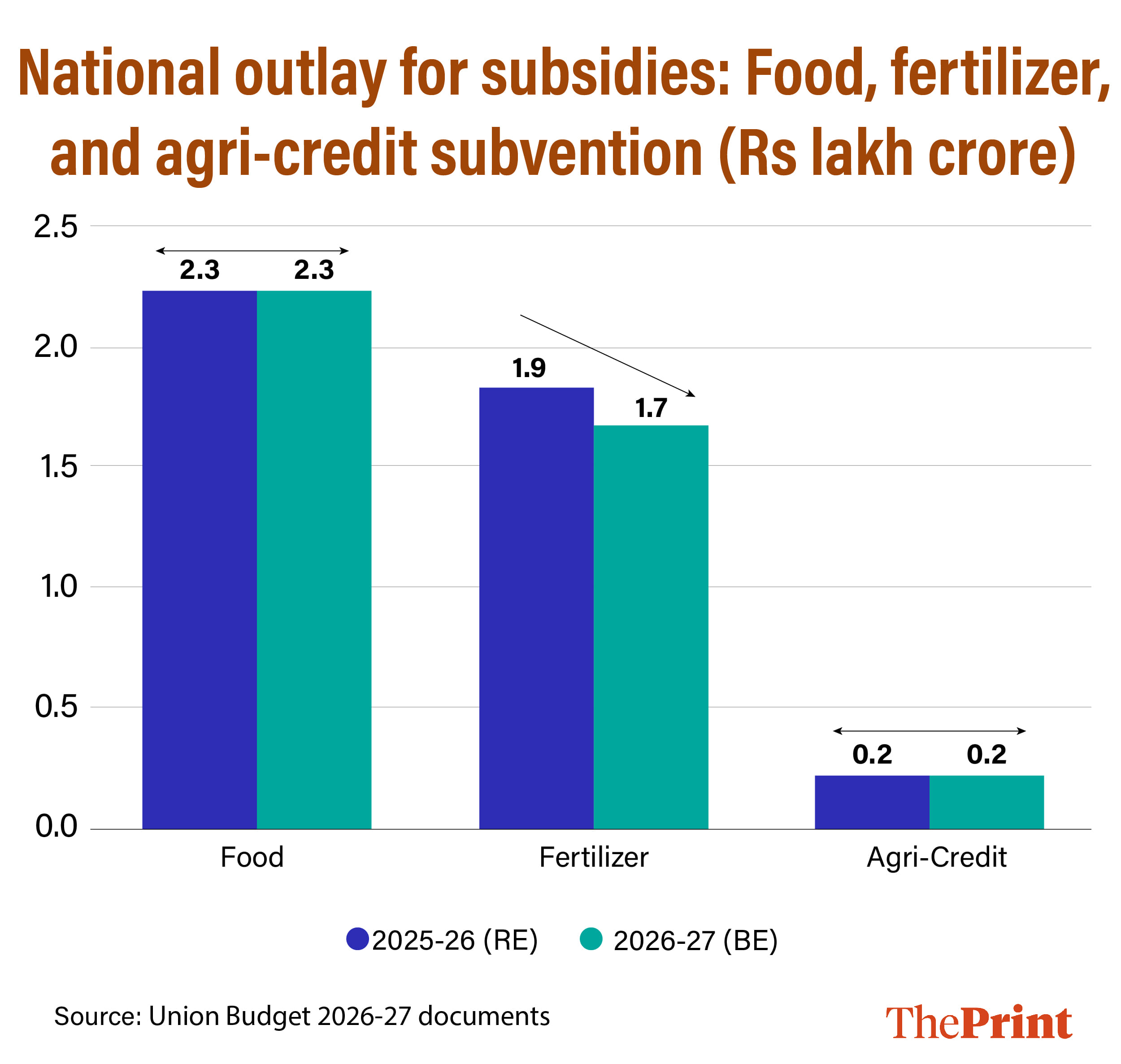

Let us first take a look at the top three subsidies that together account for about 10 per cent of the national budget.

Sitharaman noted in her speech that nearly 25 crore Indians have been lifted out of multidimensional poverty over the last decade. Yet, the Budget keeps the food subsidy outlay unchanged at Rs 2.3 lakh crore, implying the continued provisioning of free foodgrains to the 81.3 crore beneficiaries identified under the National Food Security Act, 2013. Interestingly, the Economic Survey, released three days prior, makes a strong case that India’s Public Distribution System (PDS) has been technologically strengthened through Aadhaar seeding, One Nation One Ration card (ONORC) portability, and ePoS authentication, and that these improvements now make a shift toward Direct Benefit Transfers in food both feasible and desirable to reduce leakages and improve choice.

The contrast between the Survey’s reform direction and the Budget’s status-quo allocation suggests that despite improvements in poverty indicators and delivery architecture, the food subsidy framework remains largely unchanged in FY 2026-27.

The overall outlay for fertiliser subsidy rolls back from an estimated Rs 1.9 lakh crore in 2025-26 (RE) to around Rs. 1.7 lakh crore in 2026-27 (BE), and the specific allocation for the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) component in fertiliser has been reduced to zero. The Survey presented a strong case for reconfiguring fertiliser support through a per-acre DBT model to correct nutrient imbalance and fiscal distortions. The Budget suggests a pause or recalibration in this reform pathway in the near term.

Even though overall agricultural credit flows have expanded in recent years, access remains highly uneven. Studies estimate that only about 30 to 33 per cent of Indian farmers currently tap formal institutional credit, leaving the majority dependent on informal sources or excluded entirely; coverage among small and marginal farmers is similarly low, typically not exceeding about 40 per cent. Given this structural reality, the fact that the Budget keeps the agriculture-credit outlay largely unchanged signals a business-as-usual approach to farm financing, which doesn’t address the deep access gaps.

Key initiatives in agriculture and allied sectors

Shift from crops to allied sectors as income engines: Most agricultural sector announcements are for fisheries and animal husbandry, not for crops. For fisheries, in addition to export and duty incentives for marine catch, the Budget emphasises expanding inland fisheries by developing 500 reservoirs and Amrit Sarovars, alongside investments to strengthen the coastal fisheries value chain. The Budget also suggests involving startups and women-led groups along with Fish Farmers Producer Organisations for improved marketing. For livestock, the Budget plans to invest in modernisation of infrastructure, creation of value chains, and enhanced marketing through livestock producer organisations. Rural income strategy appears to be moving from cereals to livestock, fisheries, dairy, and poultry.

Geographic crop strategy, not generic agriculture: The Finance Minister identified seven crops for focus in FY 2026-27: coconut, cocoa, cashew, almonds, walnuts, pine nuts, sandalwood. These are place-specific crops: coasts, hills, Northeast and, plantation belts. The Coconut Promotion Scheme is envisaged to increase production and enhance productivity. Additionally, a dedicated programme is proposed for Indian cashew and cocoa to enhance production and export competitiveness. This is agriculture by comparative advantage of regions.

Market access over production support: The Budget talks more about who sells than who grows. With establishment of fish and livestock FPOs, the Budget also plans to capitalise on the existing SHG initiatives to create community–owned Self-Help Entrepreneur (SHE) Marts. Additionally, the Budget offers targeted tax relief to strengthen cooperatives, including deductions for primary societies supplying member-produced inputs and for inter-cooperative dividends passed on to members. It also grants a temporary tax exemption to national cooperative federations on dividend income, provided the benefits are distributed to member cooperatives.

Logistics and trade architecture as agri policy: The Budget suggests the operationalising of the single window clearance for food, plant, animal and wild products cargo by April 2026. Additionally, further investments include AI-enabled container scanning, warehouse digitisation, and dedicated freight corridors (including waterways). These are the farm-to-port or farm-to-market reforms.

Agriculture as part of digital governance and bio-economy: The Budget proposes to launch Bharat-VISTAAR, an AI–enabled digital advisory platform. On waste to value generation, the Budget proposes to remove the excise duty payable on compressed biogas (CBG).

Also read: Budget 2026 squarely puts manufacturing at the centre of India’s growth strategy

While the Budget signals continuity in core support schemes, expenditure on schemes such as crop insurance and PM Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY) appears lower compared to outlays in FY 2025-26. Allocations for the Department of Agricultural Research and Education (DARE) and the Ministry of Food Processing Industries have also seen reductions. When adjusted for inflation, outlays on PM-KISAN, crop insurance, agricultural research, and irrigation are effectively lower in real terms. The reduced allocation for DARE suggests that while the policy direction emphasises productivity and innovation, the fiscal push behind research and long-term capacity building remains limited.

Overall, the Budget does not speak of agriculture as a standalone sector. Instead, it embeds agriculture across seven priorities — from geographic crop targeting and allied sector elevation to women-led enterprises, digital advisory systems, logistics reform, and bioenergy viability. The result is a systems approach where Sitharaman did not specify what she would do for the agriculture sector, instead she implied that she would invest to build systems in which agriculture and allied sectors perform better.

Shweta Saini is an Agricultural Economist and Co-Founder of Arcus Policy Research, where Pulkit Khatri is Senior Consultant. He tweets @pulkit7khatri. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)