Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

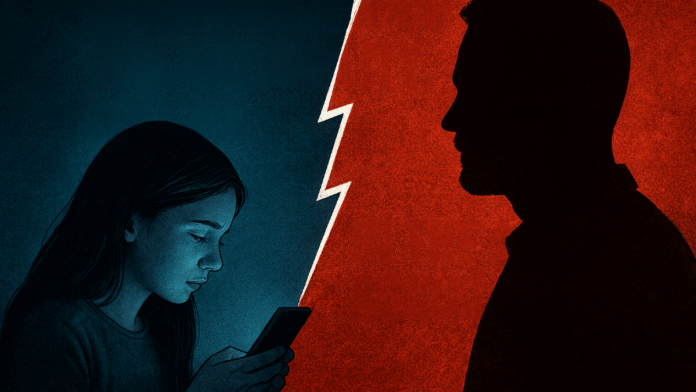

I still remember reading about Molly Russell, only fourteen, and already carrying a darkness the adults around her couldn’t see. Her father’s trembling confession, “she was trapped in a world we didn’t see,” stayed with me long after the news cycle moved on. Because Molly wasn’t an exception; she was a mirror. A mirror to every teenager who scrolls through an endless feed at midnight, their faces lit by a screen that feels safer than the real world. A mirror to the quiet battles fought behind closed doors. Doomscrolling, comparison spirals, self-worth chipped away by algorithms designed to hold attention, not protect it. Molly could have been any child, in any country, wandering through a digital maze built for engagement, not empathy. And that is what makes her story impossible to forget.

Two oceans away, governments are wrestling with similar dilemmas, though with starkly different approaches. Australia, from December 2025, has instituted a law banning social media accounts for anyone under 16. Platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, and X are now required to verify users’ ages rigorously, with fines up to AUD 50 million for non-compliance. In China, meanwhile, a different kind of regulation is emerging: influencers discussing professional or sensitive topics like finance, law, medicine, or education are now expected to have verified degrees or certifications before posting. At first glance, these rules might seem technical, legalistic, or distant. But beneath the statutes lies a shared anxiety: the struggle to protect, guide, and regulate in a world where the digital and human experience are inseparably entwined.

Australia’s law emerges from a clear, pressing concern: the mental health and safety of children. Social media has become an ever-present backdrop to teenage life, a place of connection, creativity, but also of comparison, cyberbullying, and exposure to harmful content. Studies have repeatedly shown correlations between social media overuse and anxiety, depression, and even suicidal ideation among adolescents. The Australian government, in its framing, is attempting to create a digital sanctuary, a space where minors are not exposed prematurely to the pressures, judgments, and complex realities of online life. From a policy perspective, it is logical and humane: protect the vulnerable.

Yet, as Molly Russell’s story reminded me, logic cannot fully capture lived experience. For teenagers today, social media is not merely entertainment; it is community, identity formation, and sometimes, the only avenue for self-expression. Banning access entirely risks cutting them off from friendships, peer support, and creative outlets that are crucial to their growth. Age verification systems are inherently imperfect. They cannot detect the nuances of maturity, context, or emotional resilience. And so, a law designed to shield children can unintentionally isolate them, creating new challenges even as it seeks to solve old ones.

On the other side of the spectrum lies China’s approach. Here, the concern is credibility rather than age. The government’s recent move requiring influencers discussing finance, law, medicine, or education to possess verifiable degrees reflects a deep anxiety about misinformation and public safety. The aim is clear: in domains where advice can have tangible consequences, unqualified voices must be restrained. In a society where trust in information is fragile and mistakes can cost lives, credentials become a proxy for reliability.

But the human implications are immediate and profound. Knowledge is not always formally certified. Life experience, research, or self-directed study can provide insight, perspective, and even innovation but under this rule, those voices risk exclusion. The regulation, while protecting citizens from potential harm, also risks reinforcing gatekeeping, silencing creative and critical perspectives, and constraining the diversity of discourse. For every professional with a degree, there are countless passionate individuals whose wisdom stems from lived experience, curiosity, and dialogue not diplomas.

When I juxtapose these two approaches, the human element becomes starkly visible. Both Australia and China aim to safeguard their citizens: one shields children from potential psychological harm, the other shields society from misinformation and harm resulting from unqualified advice. Both operate from concern, not malice. And yet, both reveal the tension inherent in regulating human behavior in digital spaces. Laws that are designed to protect can also constrain; measures meant to empower can sometimes limit; safeguards can inadvertently silence.

What does this mean for us as parents, educators, policymakers, and citizens? First, it underscores that digital policy is inseparable from human experience. Every regulation, every rule, ripples through lives, impacting identity, expression, and community. Second, it calls for humility. We must acknowledge that no policy can perfectly balance safety, freedom, and opportunity. Age limits cannot measure maturity; degrees cannot quantify wisdom. Third, it points to the need for multi-dimensional solutions: education on digital literacy, open dialogue between generations, transparency from platforms, and ongoing reflection on the unintended consequences of well-intentioned laws.

We are at a critical juncture in the digital age. The boss of Pinterest has told the BBC in October that the death of Molly Russell is a daily reminder of the urgent need to make social media safer for young people. The global conversation around social media regulation whether it is Australia’s age-based ban or China’s credential requirement is not simply about law and policy; it is about trust, responsibility, and humanity. It is about asking, as we draft rules for digital spaces, whose voices are protected and whose are muffled. It is about balancing the imperatives of safety, credibility, and freedom. And, perhaps most importantly, it is about listening to those who are most affected: teenagers navigating their first online communities, aspiring content creators building their platforms, and ordinary citizens seeking reliable information in a crowded digital landscape.

Another night after droomscrolling, I sat quietly, reflecting on the weight of these decisions. I understood the intention behind Australia’s law and the rationale behind China’s credential requirement. Yet, I also understood the heartbreak, the frustration, and the stifled creativity that accompanies any blanket rule. The digital world is not merely a marketplace of ideas; it is a space of relationships, self-expression, and discovery. And as societies worldwide grapple with how to protect, guide, and regulate this space, we must never forget that at the heart of these laws are real people, with real feelings, dreams, and fears.

In the end, technology and policy are only as humane as the people who shape them. We must strive to design systems that safeguard without silencing, that educate without excluding, that protect without alienating. Because behind every law, every rule, and every regulation, there is a human story waiting to be heard, a story of curiosity, creativity, and connection. And perhaps, if we are attentive enough, the laws of tomorrow can be informed not just by statistics or risk, but by empathy and understanding, ensuring that the digital world remains not only safe but truly human.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.