Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

The state of affair can be gauged from the fact that I didn’t title my passage as ‘What Corporate can Learn from Team India’ – a hint on how things have precipitated for Men in Blue (and White). The English game of cricket has seen many cycles—the proliferation of the game from the classes to masses, rise and fall of ferocious West Indies team, the systematic and systemic phenomenon called Cricket Australia, and ever-expectant-glory-seeking Team India. From the days of 10 men around Tendulkar to the 2011 World Cup, the team saw several characters emerging, formats being tested and experiments with the team composition. Even the IPL played a cameo offering a long tail and selectors some breathing space, but all of that seems to be overdone. Resultingly, today we stare at a stratified team, backpacking from one contest to another— with neither sufficient time to celebrate success nor enough room to reflect on failures. Yes, relentless pace can be a reason, but at least the world of cricket doesn’t have quarterly pressure. Let’s learn from the world where a quarter is not just three months.

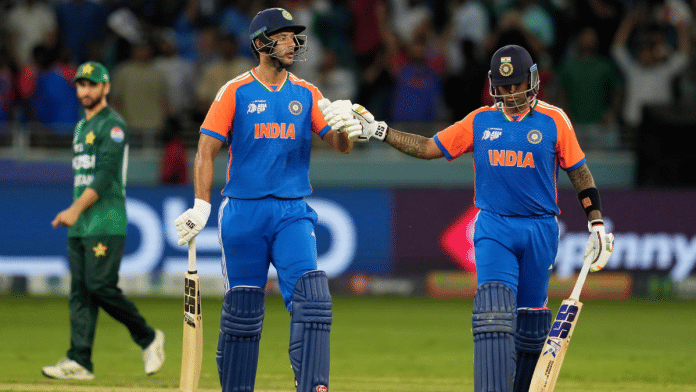

What if a company rotates its leadership team every season—starting at the very top? Will anybody be able to think long term? Won’t everyone be in a self-preservation mode? That’s the staple with the Indian cricket team. In the last five years, across the three formats – Test, One Days and Twenty20—no more than two players are common per season. Even in the same tour, as seen in the recent exploits down-under, there’s hardly any consistency across the week. Even the captain sits on the musical chair. Resultingly, there’s hardly a team cohesion, implicit understanding between players, and a room to reflect and improve. When a player knows that his candidature is just ten overs long, where’s time to settle. The case with Kohli and Sharma were emblematic of the phenomenon. Thankfully Sharma bagged the Player of the Match trophy.

The argument favouring this fine dicing of talent is specialization that a Test player needs technique, a One Dayer needs temperament, and Twenty20 thrives on raw aggression. But aren’t we talking of the very same game? Weren’t the best players of the bygone era equally deft across the two sane formats? On the contrary, the longer and shorter constructs offer a positive feedback loop, ironing out the kinks and help building new competencies. Ergo, we witnessed the Golden Era of Indian cricket, culminating into the 2011 and 2013 pinnacles. The specialization theory, gaining rapid currency in the current dispensation under Coach Gambhir, is already seeing cracks. Players, severely short of practice and rest, play a Test akin to a relay of Twenty20 matches – surviving one session at a time. The specialist players know that it’s now or never, and the Twenty20 players don’t even aspire for the baggy.

The billion-dollar enterprise called IPL, which promised and did deliver a bench, only exacerbates the problem. The selectors are spoilt for choice, the coach is more of a juggler, the captains are mere uber-players, and the team keeps an eye glued on the Reservation Against Cancellation (RAC) chart. The players – both on and off the field— survive on high doses of anxiety punctuated with blinding spotlights. Only person presumably confident of a candidature is Coach Gambhir, who should be ceremoniously sacked, for he has set a new low on leadership. Yes, there are no good teams or bad teams, there are only good leaders and bad leaders. And the appeal is not even on moral grounds, the data speaks it all.

As for the corporate India, which is making its presence felt both in the face of global headwinds and domestic tailwinds, two insights are instructive. Firstly longevity. There’s comprehensive evidence suggesting that long term growth and capital formation hinges on the CEO tenure—you won’t invest for making your successor look good next quarter. I am not indicating a five-year tenure (and why not), but at least a consistency and a latitude to experiment, fail, revive and cherish. Let’s not fool ourselves into thinking that cricket faces more dynamism than the corporates.

Secondly, peddle back on the fine division of labour and super-specialization. A Sehwag or a Ganguli resulted from longer gestation periods and shone in all formats and in most testing conditions. Even Dhoni, who was forced to double down on the shorter, more desperate formats, did reasonably well (by present standards) in the longer formats, except that his self-righteousness got the better of him. There’s enough research backing and practical evidence suggesting the limits of specialization—it helps in getting speed but not improvement. By slotting players tightly in the batting order (which looks laughable in the Twenty20 version) you are making system weak and on the behest of those pegs. As managers graduate, they become general managers. How about players?

I won’t offer the third advice, for cricket in India espouses raw emotions, which most corporate fail to (rightly so), but it’s worth a consideration that the vulgarity of IPL auction be checked. Much like the corporate watchdogs in India, like Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) and the Competition Commission of India (CCI), cricket too needs checks, other than hysterical crowds, to keep the spirit of the game alive. My real fear is of the economics taking away patriotism from the game. Till such time, let the crowd bring in the next generation to watch the Men in White, and please leave the Women in Blue alone.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.