Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

The Aravalli Range is rarely mentioned in prime-time debates. When they do, the topic is typically portrayed as a technical dispute—over property records, mining rights, or development clearances. However, the stealthy destruction of the Aravallis is more than just an environmental concern. It is a structural governance failure with direct implications for the future of urban India.

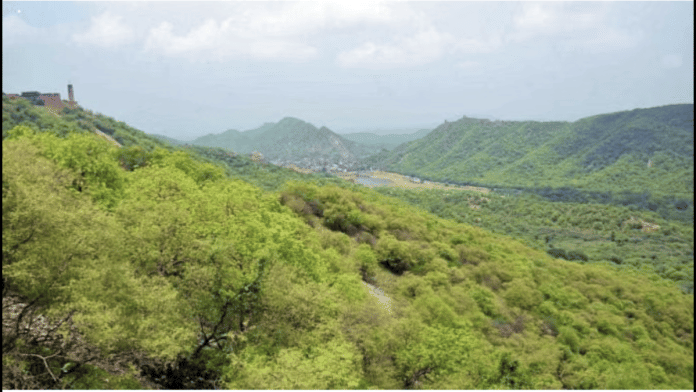

The Aravallis are one of the world’s oldest mountain systems, stretching across Rajasthan, Haryana, Gujarat, and Delhi. Their importance today is based on their function rather than their antiquity. They delay desertification from the west, recharge groundwater aquifers, moderate regional temperatures, and serve as a pollution sink in the National Capital Region. In a warming, water-stressed North India, this makes them essential infrastructure, albeit natural rather than constructed.

Nonetheless, they are viewed as expendable. In the last 20 years, mistakes made by the government have slowly changed the borders of the Aravallis, especially around Gurugram and Faridabad. To help development, forest classifications are made shorter, land-use categories are changed, and long-standing protections for the environment are made weaker.

This move indicates a more fundamental shift in how land is valued. Ecological function no longer has institutional weight unless it can be monetized. Hills become “wasteland,” forests become “vacant land,” and landscapes that manage water and heat are included into urban development plans. The irony is that these decisions are frequently framed as pro-growth. In truth, they are externalizing costs that cities will bear for decades. The Aravallis’ ecological importance has been recognized by Indian courts on numerous occasions, with mining restrictions and a focus on conservation. Scientific agencies have often warned about groundwater depletion and microclimate disturbance if degradation continues.

However, enforcement remains unequal. State governments frequently rely on technical loopholes, such as whether land was declared forest before a specified cut-off year or whether mining activity predates environmental legislation. The end outcome is a governance gap in which protection exists in theory but not in practice. This is not the absence of law. It’s selective compliance.

The degradation of the Aravallis is closely linked to the current difficulties in NCR cities. The problems of rising heat stress, falling groundwater tables, flooding after short bursts of rain, and getting worse air quality are not unique. They show that natural systems are falling apart faster than man-made structures can fix them.

Ruining natural heat buffers and recharge zones exacerbates global warming for people living in cities.

This is how climate change affects cities. People who support the ongoing construction say that protecting the environment slows down progress. The framing is misleading. The actual trade-off is between short-term benefits and long-term viability. Cities like Gurugram already demonstrate the consequences of ignoring ecological limits—water tankers as permanent infrastructure, electrical systems overloaded with cooling demand, and mounting public health hazards. Undermining the Aravallis exacerbates these vulnerabilities.

The Aravallis are not against development. They’re anti-collapse. What makes the Aravalli narrative politically significant is what it represents. If a landscape with demonstrable scientific worth, repeated judicial endorsement, and national significance can be gradually demolished, then environmental governance elsewhere is also vulnerable.

India’s global climate posture is increasingly based on assertions of responsible development and resilience. However, domestic moderation is necessary for international credibility. Protecting the Aravallis is not just symbolic; it is critical to whether India’s growth model can withstand climate change.The Aravallis do not require cosmetic afforestation initiatives or verbal commitments. They require clear land-use protection, institutional cooperation, and political recognition that some natural systems cannot be traded away.

India’s oldest mountains are issuing a modern warning. Ignoring it could be even more costly than the growth they are said to block.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.