Hidden deep in the sandstone hills of Madhya Pradesh, about 45 kilometres southeast of Bhopal, lies a landscape that has witnessed the birth of human creativity. The Bhimbetka Rock Shelters, spread across seven hills and over 750 caves, stand as one of the world’s oldest testaments to imagination, a prehistoric art gallery carved and painted long before history began. Here, humanity’s first thoughts, fears, and dreams were etched not on paper or clay, but on the living face of stone.

Where the Human Story Began

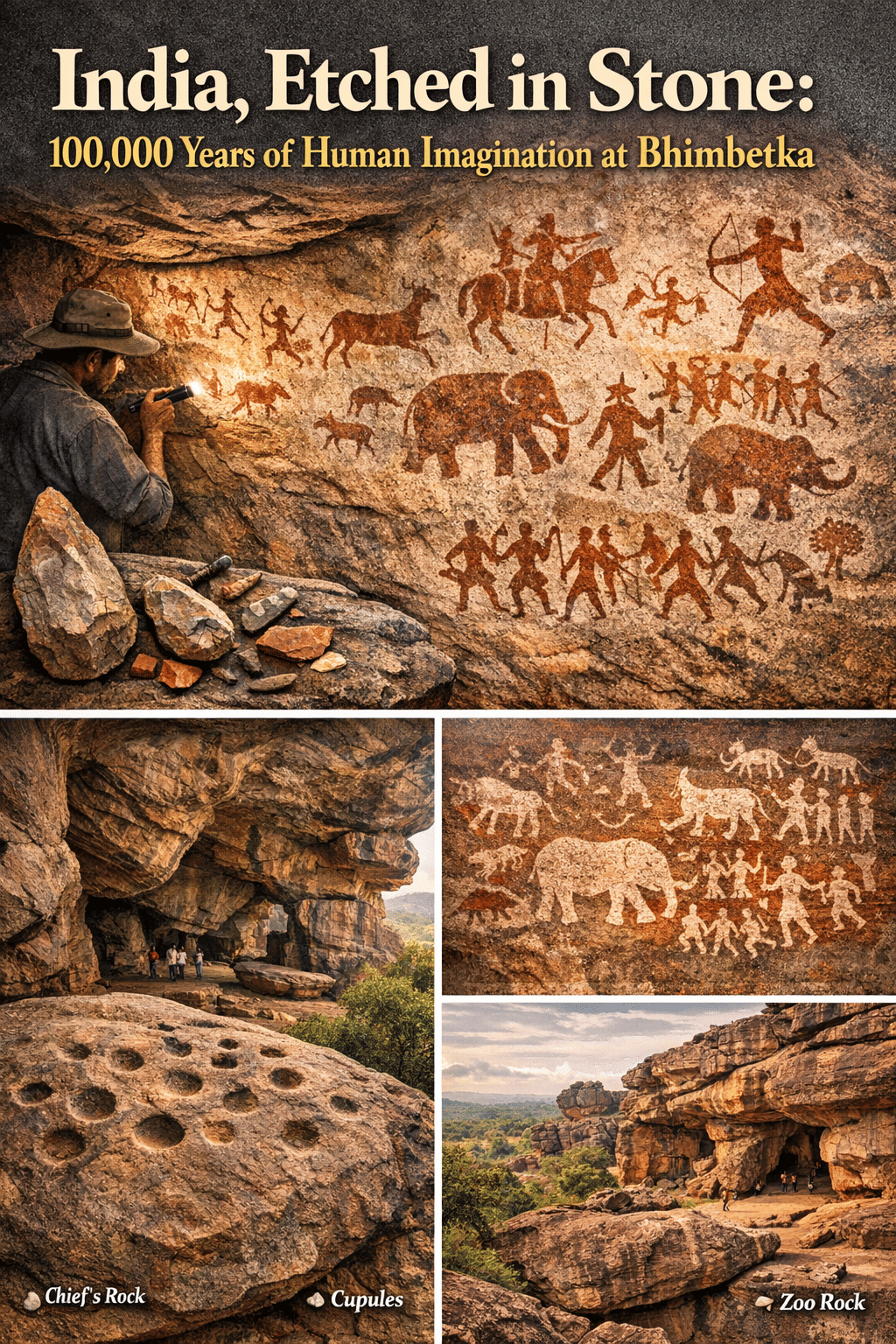

Long before the words “India” or “civilization” were coined, this land was already home to artists and hunters. The Bhimbetka site, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, captures the continuous presence of human life from the Lower Palaeolithic Age, roughly 100,000 years ago, to the Medieval period. Few places on Earth can boast such an unbroken timeline of human evolution and cultural change.

The site was first brought to scholarly attention in 1957 by archaeologist V. S. Wakankar, who spotted the unusual rock formations while traveling near Bhopal. He recognized in them the same kind of prehistoric shelters he had seen in Spain’s Altamira and France’s Lascaux, the cradle of European cave art. What followed was a revelation: a network of rock shelters filled with artifacts, paintings, and traces of daily life spanning tens of millennia.

The landscape of Bhimbetka is not merely a set of caves; it is an open-air museum chronicling the journey from the earliest stone tools to the dawn of organized society. The Archaeological Survey of India describes it as “a living laboratory of human evolution,” a rare continuum of art, technology, and thought.

Tools of Survival, Symbols of Progress

Archaeologists excavating Bhimbetka have unearthed a remarkable range of artifacts, each layer revealing a new chapter in human development. The earliest tools, belonging to the Acheulean phase, include rough hand axes and cleavers crafted from quartzite and sandstone. These were humanity’s first inventions: multipurpose instruments that shaped both environment and destiny.

As time progressed, so did technology. The Mesolithic period introduced microliths, tiny, razor-sharp blades often attached to wooden handles or bone shafts, forming spears and arrows. Their precision spoke of evolving intelligence, foresight, and collaboration in hunting and survival.

By the Chalcolithic era, pottery fragments, bone tools, and ornaments suggest a shift from pure survival to culture. Painted pottery and red-and-grey wares hint at trade with nearby agricultural communities like those in the Malwa plains. Beads of steatite and shell, along with copper tools and early coins, mark the beginnings of economy and ornamentation, the roots of civilization itself.

Even architecture found its first expression here. Some shelters feature stone walls, carved steps, and levelled floors, among the oldest in the world, revealing that humanity had begun to shape spaces not just for living, but for belonging.

The World’s First Canvas

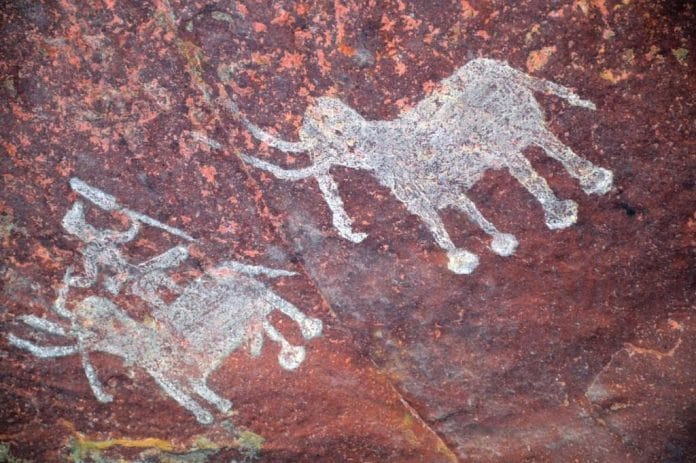

If Bhimbetka’s tools speak of survival, its paintings speak of spirit. The rock art of Bhimbetka, dating as far back as 10,000 BCE, is India’s oldest known artistic heritage. Spread across more than 500 caves, these paintings record the evolution of thought, ritual, and emotion.

Archaeologists categorize the art into seven distinct periods, ranging from the Upper Palaeolithic to the Medieval Age.

- The earliest are simple green stick figures of humans dancing and hunting.

- Later scenes become more expressive: tribal dances, group hunts, men on horseback, and even ritual gatherings.

- By the Chalcolithic period, figures show interactions between hunter-gatherers and settled farmers, suggesting exchange and coexistence.

- The later historic and medieval paintings include symbols of religion and power, deities, warriors, and chariots.

Natural pigments, red from hematite, white from kaolin, green from earth, and black from manganese, were mixed with animal fat or plant resin. Despite the passing of millennia, these colours have endured, protected by the dry climate and the shelter of the overhanging rock.

Each painting tells a story: hunters chasing deer, dancers circling a fire, mothers cradling children. One cave nicknamed the “Zoo Rock,” bursts with depictions of elephants, bison, barasingha (swamp deer), and peacocks, a prehistoric safari frozen in time. In another, a lone man faces a charging bison, his companions standing helplessly nearby, a moment of tension and humanity captured forever in ochre lines.

Among the most evocative images is the so-called “Nataraj” figure, a man holding a trident-like staff and dancing, unearthed by Wakankar himself. It hints at ritual, rhythm, and perhaps the earliest roots of spirituality in the subcontinent.

The Cathedral of the Stone Age

At the heart of Bhimbetka lies the Auditorium Cave, a monumental chamber surrounded by towering quartzite cliffs. Archaeologist Robert G. Bednarik once described it as having a “cathedral-like atmosphere”, its natural arches and soaring walls resonating with an almost sacred stillness.

At the entrance stands the Chief’s Rock, bearing mysterious cup-shaped depressions known as cupules, carved nearly 100,000 years ago. These are the world’s oldest known rock engravings, older than writing, older than farming, older than civilization itself.

No one knows what they meant. Were they part of a ritual? A counting system? Or simply the first artistic impulse, to leave a mark, to say “I was here”? Whatever their purpose, these tiny depressions represent the dawn of symbolic thought: the beginning of humanity’s inner life.

The Myth, the Misstep, and the Meaning

In local folklore, “Bhimbetka” means Bhima’s seat, the resting place of the mighty Pandava warrior from the Mahabharata. Legend has it that Bhima once sat here to meditate, turning the rocks into stone witnesses of his power. While the myth is a product of later centuries, it reflects something universal: the human need to connect with those who came before.

Even in modern science, Bhimbetka continues to provoke debate. In 2021, geologists claimed to have found fossils of Dickinsonia tenuis, an ancient life form from 550 million years ago, within the site. The claim, if true, would have rewritten the geological history of India. But later studies revealed the “fossils” were actually remnants of ancient beehives, a humbling reminder that even science, like myth, is part of an ongoing conversation with the past.

A Legacy Written in Stone

Today, Bhimbetka stands as more than an archaeological site, it is a mirror reflecting who we are and where we began. Its walls hold not just art but empathy; not just symbols but stories. In a single brushstroke from 10,000 BCE, we can see the same curiosity, the same need to create, that drives us today.

Conservation remains a challenge. Erosion, pollution, and careless tourism threaten the delicate paintings. The Archaeological Survey of India, with help from UNESCO, continues to protect and document the site. Yet, its greatest safeguard may be awareness, reminding future generations that these shelters are not relics of a vanished people but the roots of our shared imagination. As the sun dips over the Vindhya hills, the red stones of Bhimbetka glow softly, the same light that once guided the hands of ancient painters. Their stories remain etched in silence, waiting for us to listen.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.