Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/

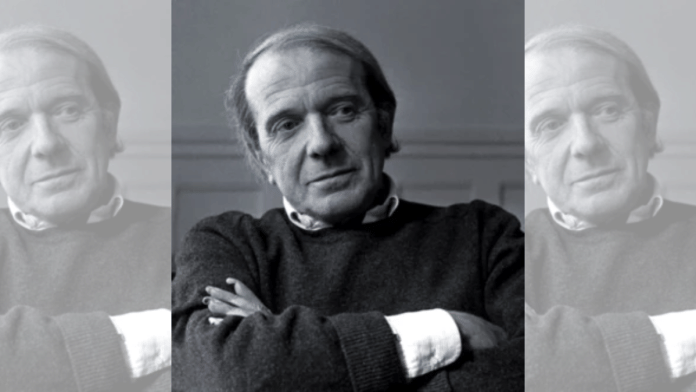

Imagine a philosopher who hated definitions. Who believed that identity is overrated, that thinking is an act of resistance, and that desire is not about lack but production. A man who argued that books should not be read for meaning, but for their power to make you think differently. Welcome to the fascinating, zigzagging mind of Gilles Deleuze, the French philosopher who turned thought into an art form and who may have been the most creative thinker of the 20th century. This is not your average philosopher. Deleuze didn’t write books to be understood. He wrote them to disturb, disrupt, and rewire the mind. Reading him is like wandering through a dream: ideas stretch, bend, morph. There’s no neat beginning or end. And that’s exactly the point.

A Life Off the Grid

Born in Paris in 1925, Gilles Deleuze grew up in an occupied France during World War II. As a young man, he took up philosophy not as a path to answers, but as a way to ask better stranger questions. He wasn’t a bohemian, nor a revolutionary in the street-fighting sense he detested the cult of personality but he was a revolutionary of thought. When he met psychoanalyst Félix Guattari in the late 1960s, the duo would go on to rewrite the rules of what philosophy could be. Deleuze was elusive in life and enigmatic in death. He suffered from a debilitating lung disease for much of his later life and ultimately died by suicide in 1995. Yet his philosophical output especially the collaborations with Guattari remains a heady blend of metaphysics, art theory, psychoanalysis, political activism, and avant-garde inspiration. His work is not a system to be followed but a toolkit to be used. As he famously put it, “A concept is a brick. It can be used to build a courthouse of reason. Or it can be thrown through the window.”

What is Philosophy? A Playground of Ideas

To understand Deleuze is to stop asking, “What does this mean?” and start asking, “What does this do to my thinking?” He saw philosophy as concept creation, not explanation. For him, concepts were alive dynamic, nomadic, and unpredictable. He wanted to create ideas that broke free from academic cages and ran wild across disciplines. Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus is perhaps the best example of this anti-linear, rhizomatic style. The book famously advises: “Begin anywhere.” It’s a philosophy of horizontal thinking: no hierarchies, no clear map. Just connections endless, proliferating, unexpected. This is the “rhizome” one of Deleuze’s most famous concepts. Imagine the underground root system of ginger or grass: no central trunk, no beginning or end, just constant growth in multiple directions. That, for Deleuze, is how thought should work. Not like a tree (structured, hierarchical), but like a rhizome constantly evolving, connecting, and decentralizing.

Desire: Not What You Think

Perhaps Deleuze’s most radical idea was that desire is not born of lack. Traditional psychoanalysis (think Freud and Lacan) treated desire as a symptom something we long for because we do not have it. Deleuze and Guattari rejected this model. For them, desire is productive. It creates, assembles, and flows. It’s not about what we don’t have, but about what we can make. In their mind-bending book Anti-Oedipus, the duo argued that society represses desire not just sexually, but politically. We are taught to internalize limits, to desire conformity, and to think within boxes. For Deleuze, freedom means unleashing the full, creative force of desire that he called “desiring production.” It’s not about breaking rules for the sake of it. It’s about reimagining the entire game.

Films, Painters, and Proust: Philosophy Through Art

Deleuze wasn’t just interested in philosophy he adored cinema, literature, and painting. He wrote entire books on filmmakers (Cinema 1, Cinema 2), writers like Proust and Kafka, and artists like Francis Bacon. He didn’t treat art as something to analyze. He treated it as a mode of thought a way of philosophizing with images, sounds, and gestures. His writings on film are particularly rich. He saw cinema as a way to stretch time, to break the habitual way we experience movement and perception. He spoke of “movement-images” and “time-images,” proposing that films can do philosophy by presenting time not as clock-ticks, but as lived intensity.

In Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, Deleuze explores how the painter doesn’t represent but forces sensation onto the canvas. For Deleuze, this is what philosophy should do to not explain the world, but shake it. Not represent reality, but create new ways of seeing.

The Art of Transformation

Another central Deleuzian concept is “becoming.” Unlike identity, which is fixed and stable, becoming is always in flux. A child becomes an adult, a melody becomes noise, a man becomes a wolf (becoming an animal), and a woman becomes wind (becoming imperceptible). For Deleuze, identity is an illusion what matters is transformation. These “becomings” are not metaphors. They are processes of change and creative experiments with self and world. “To become” means to engage in metamorphosis, to disrupt the binaries of human/animal, male/female, self/other. It’s about exploring the spaces in between. In a world increasingly obsessed with labels, tribes, and fixed identities, Deleuze offers a wild, liberating alternative: you are not a thing; you are a process.

Against the State, Against the System

Deleuze was deeply political, but never in the traditional sense. He didn’t trust institutions, ideologies, or centralized power. He called the state “the great organizer of repression,” and saw capitalism as a machine that captures desire, channels it into consumerism, and stifles creativity. Yet he didn’t believe in simple revolution either. He spoke of “lines of flight” small escapes, unexpected transformations, and molecular revolts. He championed micro-politics over grand ideologies and assemblages over institutions. It’s not about seizing power, but about fleeing from it in inventive ways. His political vision was deeply ecological, too less about humans dominating the planet, and more about seeing ourselves as part of intricate assemblages of nature, machines, bodies, and ideas. In this way, Deleuze anticipates much of today’s posthuman and environmental thinking.

The Philosopher of the Future

Why read Deleuze today? Because he speaks to a world drowning in algorithms, categories, and capitalist control. Because he challenges us to stop thinking in pre-made patterns. Because he invites us to experiment with thought, not just follow it. His philosophy isn’t easy, but it’s electric. It doesn’t just fill your head it reprograms it. In a time of increasing surveillance, conformity, and commodified identity, Deleuze remains an anarchic whisper in the brain: “You are more than this. You can think otherwise. You can be otherwise.” And maybe that’s his greatest gift: the reminder that philosophy isn’t about finding answers. It’s about opening up new ways of living, feeling, and becoming.

Five Strange and Beautiful Deleuzian Concepts

Rhizome: A way of thinking without hierarchy. Non-linear, decentralized, messy. Think roots, not trees.

Desiring-Production: Desire is not lack; it creates. It’s a machine, not a hole.

Becoming Animal: We don’t imitate animals. We undergo metamorphosis. A man doesn’t act like a wolf; he becomes a wolf.

Assemblage: Everything is a temporary collection of relations people, machines, laws, and ecosystems. Nothing is fixed.

Lines of Flight: Escape routes from dominant systems. Not exits, but creative detours.

Deleuze and India: A Hidden Resonance

Gilles Deleuze never directly engaged with India in the way that some Western philosophers or artists did (like Foucault’s commentary on Iranian politics or Heidegger’s influence on Eastern thought), but his philosophical ideas resonate deeply with Indian thought, and several indirect connections can be drawn that are both intriguing and meaningful. Though Gilles Deleuze never visited India nor wrote explicitly about it, echoes of Indian philosophy reverberate through his work in surprising and profound ways. His ideas born in the post-structuralist ferment of postwar France find strange kinships with ancient Indian traditions that go far beyond the surface.

Take, for instance, Deleuze’s concept of “becoming” a dynamic, never-finished process of transformation. This finds a striking parallel in Hindu and Buddhist philosophies, where the self is seen not as a fixed identity, but as a fluid interplay of consciousness, karma, and impermanence. The Advaita Vedanta rejection of a permanent ego, or the Buddhist notion of Anatta (non-self), feels remarkably close to Deleuze’s anti-essentialism.

Then there’s his critique of hierarchical thought and his preference for the rhizome over the tree. Traditional Indian logic often moves in non-binary, cyclical patterns, such as the Chatuskoti (four-cornered logic) of Buddhist Madhyamaka, which challenges rigid dichotomies and linear reasoning. Deleuze might have seen a fellow traveler in Nāgārjuna, who dismantled fixed views through paradox and negation. Even Deleuze’s interest in multiplicity, immanence, and the body as a field of forces mirrors the tantric and yogic traditions of India, where the body is not a prison of the soul but a microcosmic cosmos in constant transformation.

In contemporary India, Deleuze’s philosophy has also inspired critical theory, film studies, art practices, and postcolonial thought. Scholars and artists have drawn from his work to challenge the linear narratives of modernity, nationalism, and development. So while Deleuze himself may not have gazed eastward, India has found him in the classroom, in art galleries, and political critique. The conversation, it turns out, was always rhizomatic.

In conclusion, to read Gilles Deleuze is not to “learn philosophy” in the classical sense. It’s to unlearn, to deconstruct, to be pulled into a whirlwind of concepts that move like jazz. His thoughts are messy, strange, ecstatic and deeply needed in a world that too often demands coherence, control, and clarity. Deleuze teaches us to revel in difference, to mistrust certainty, and to follow the wild lines of becoming wherever they lead. And if you find yourself confused, disoriented, maybe even a little thrilled that’s exactly how he’d want you to feel.

Vaithianathan Kannan

email: kannan.vaithianathan@gmail.com

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.