Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

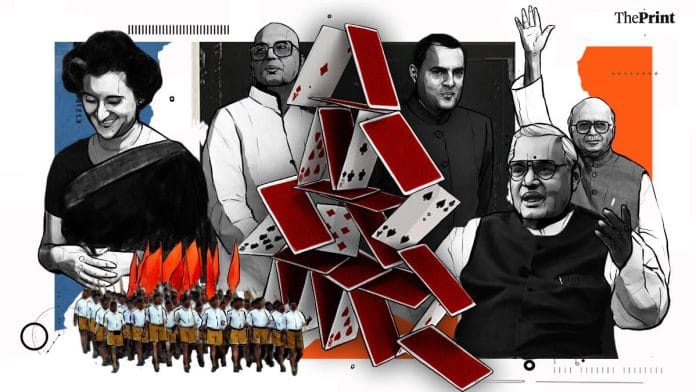

Political slogans in India have rarely been empty words. They have crystallised the demands of their times and often shaped electoral outcomes. When Indira Gandhi coined “Roti, Kapda, Makaan” in 1971, it resonated in a country where more than half the population lived below the poverty line. The phrase symbolised a state promise to secure life’s essentials and gave Congress a simple yet powerful vocabulary to dominate Indian politics. It was universal, cutting across caste, region, and religion, and it worked.

By the late 1980s, however, the grammar of politics changed. The implementation of the Mandal Commission by V.P. Singh institutionalised caste identity in governance. Uttar Pradesh became the testing ground where leaders like Mulayam Singh Yadav converted Mandal into durable political coalitions. Congress, still relying on universalist welfare language, struggled to adapt. The political question shifted from “what does society need?” to “who has been excluded?” Recognition replaced redistribution as the rallying cry.

Today’s PDA slogan—Pichhda, Dalit, Alpashankhyak—represents the latest stage of this trajectory. Unlike “Roti, Kapda, Makaan,” which was inclusive of all, PDA is identity-conscious, crafted to consolidate historically marginalised groups. It seeks to promise both recognition and development, yet tensions within the coalition remain sharp. Yadavs and non-Yadav OBCs, Jatavs and other Dalits, Ashrafs and Pasmandas within Muslims—each carries its own grievances. The political challenge lies in translating symbolic recognition into tangible outcomes that satisfy these diverse groups.

The record so far is mixed. Under Akhilesh Yadav, projects like the Lucknow Metro, the Agra-Lucknow Expressway, and the Gomti Riverfront symbolised modernisation. These were visible achievements but often criticised as urban-centric. Congress governments, on the other hand, relied on universal schemes: MGNREGA provided rural employment, the Right to Information empowered citizens, and the Right to Food expanded the welfare net. Both approaches delivered, but unevenly. Data continues to show stubborn disparities—unemployment among rural Dalit and OBC youth remains far higher than the national average, healthcare access varies sharply by caste and religion, and Muslims, especially Pasmandas, lag behind in education and jobs. The gap between recognition and redistribution persists.

This gap is also political. A significant portion of non-Yadav OBCs has drifted towards the BJP, attracted by its Hindutva narrative combined with targeted welfare schemes such as free ration and housing. Similarly, within Muslims, the Pasmanda discourse challenges traditional elite (Ashraf-dominated) leadership, questioning whether PDA can truly address their aspirations. Thus, while PDA offers a slogan of unity, the ground reality reflects fragmentation.

The Congress–Samajwadi Party alliance attempts to bridge this divide. Congress brings a legacy of universal welfare guarantees, while SP brings the muscle of identity mobilisation. In theory, the combination can broaden the coalition—Congress appealing to the urban middle class and aspirational youth, SP assuring representation to OBCs, Dalits, and minorities. If successful, it could be a synthesis of redistribution and recognition. But risks remain. Overlapping promises can blur clarity, and voters have grown sceptical of slogans that fail to convert into measurable gains.

The longer trajectory from “Roti, Kapda, Makaan” to PDA thus tells the story of Indian democracy’s evolution. The first slogan spoke of what citizens require to live with dignity. The second asks who continues to remain outside that dignity despite decades of welfare. Both highlight progress as well as unfinished business. India has moved from demanding survival to demanding justice, but the bridge between recognition and real transformation is still fragile.

The lesson is clear. Political catchphrases cannot substitute for delivery. Schools must function, hospitals must heal, jobs must uplift, and dignity must be felt daily. Recognition without redistribution risks deepening divisions; redistribution without recognition risks invisibilising the excluded. Only their combination can turn rhetoric into genuine change.

The future of social justice politics may depend on whether the Congress–Samajwadi Party experiment can achieve this balance. If it does, PDA may evolve beyond a slogan into a framework where recognition and welfare walk hand in hand. If not, it risks joining the long list of phrases that inspired momentarily but failed to alter realities. Ultimately, Indian politics will not be judged by its words but by whether citizens can touch, see, and live the transformation promised to them.

Author

Dr. Anvveshan Singh

Assistant Professor of Journalism at DDU Gorakhpur University, is also a noted political critic, known for his insightful analysis of politics, media, and public discourse.

Contact no.9623438916

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.

सटीक विश्लेषण