Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/

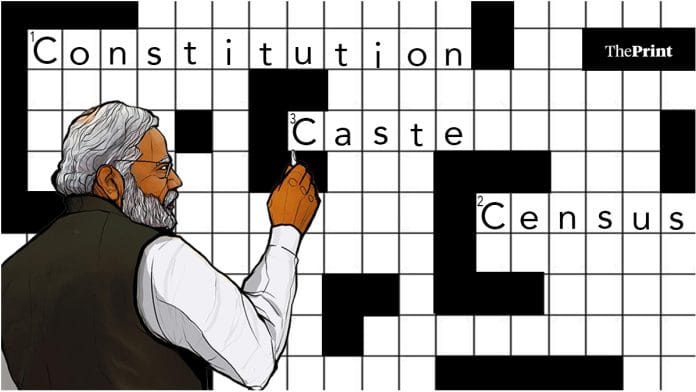

The concept of a nation, which refers to a group of people with boundaries based on factors like ethnicity, colour, culture, customs, religion, etc., has been a topic of contention across the world. On the other hand, caste is a particularly significant factor in India. The United States-based economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Jonson, and James A. Robinson received the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in 2024 by the Royal Swedish Academy for Sciences in honor of Alfred Nobel, “for studies of how institutions evolve and affect prosperity.” (Indian Express, October 16, 2024, p. 12)

The excellent book “Why Nations Fail” was written in 2012 by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, in which they mentioned components of a successful or failed nation because it would depend on a nation’s policies to determine whether it succeeds or fails. Like the USA, UK, Germany, and Italy, these countries have been adopting inclusive economic, political, and social policies and have been growing into powerful nations. In this book, they describe the example of Zimbabwe, where in January 2000, a national lottery was run by the Zimbabwe Banking Corporation (Zimbank), a bank that was partially controlled by the state. All customers who maintained $5,000 or more in Zimbabwean dollars in their accounts as of December 1999 were eligible for the lottery. Z$ 100,000 was the lottery prize. But the most unexpected revelation was that it was won by the president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, who had controlled the country since 1980 by hook and crook—mostly with an iron fist. He had earned a huge amount of state money by lottery. Zimbank asserted that Mr. Mugabe’s name was selected from a pool of thousands of qualified clients nevertheless. The lottery ticket showed exploitative institutions that exist in Zimbabwe. This may be referred to as corruption, but it was only an illustration of an exclusive system.

Dalits have the same story; their share in the system has been less than that of their population, alike, and Dalits are incensed over the fact that the judiciary is made up of members of a small number of castes or families while all ragpickers and sanitation workers are inevitably from the same caste. which shows that caste would be an important factor for the future of India.

However, caste has been a persistent and defining principle of inequality and discrimination in India. In recent decades, this has become a more visible issue outside India. Caste discrimination: A Global concern report, demonstrated on Dalits, or so-called untouchables, of South Asia, including Nepal, Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan. which shows that Dalits have been excluded from the system with structural mechanisms. However, Dalits have been aware of their rights and assertions. Simultaneously, human rights groups, including the Dalit Solidarity Networks around the world, have been confronting the oppression of Dalits and advocating for inclusive policies. Dehumanizing Dalits was the practice in Indian society. Dalits were considered the lowest group in the caste hierarchy—lacked legal protection against discrimination; they were/are facing atrocities by so-called upper castes. The government acknowledged the existence of caste discrimination and gave space to Dalits in the Legislature, Executive, and Judiciary.

Therefore, Isabell Wilkerson spoke about the origin of caste—the word caste, which has become synonymous with India, came from the Portuguese word casta, a Renaissance-era word for “race” or “breed.” The Portuguese, who were among the earliest European traders in South Asia, applied the term to the people of India upon observing Hindu divisions. Thus, a word we now ascribe to India arose from Europeans’ interpretations of what they saw; it sprang from the Western culture that created America.

She argued that in the USA, racism maintains only social hierarchy, for while blacks are in the minority in there, they were able to achieve the top position in politics when Barack Obama became the first black President of the USA. After the election, white Americans in both parties claimed that racism was a thing of the past in the USA. “We have a black president, for heaven’s sake.” They proclaimed a new post-racial world, but as per data, the majority of white Americans didn’t vote for the country’s first black president. An estimated 43 percent went to him in 2008 and 39 percent to him in 2012. Which shows race is a big matter for Americans also. But India is not yet able to have a Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe’s Prime Minister. It could be observed that the dynamics of caste in India are shaped by religious affiliation, which makes the Indian caste system more and more rigid than the USA’s racism. Another issue is global economic disparity, which has been rising steadily since 2020, according to an Oxfam study (2024) that revealed that although over five billion people have become poorer, the wealth of the wealthiest individuals has doubled. In the context of India, caste is the biggest matter, for it causes poverty, discrimination, exploitation, and disparity on a political and economic level.

Author

Dr. Krishan Kumar

Political Sociologist and expert on caste issues in Haryana, Assistant Professor of Political

Science, Lovely Professional University, Punjab.

EI- krisjhankumar1794@gmail.com

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.