Thank you dear subscribers, we are overwhelmed with your response.

Your Turn is a unique section from ThePrint featuring points of view from its subscribers. If you are a subscriber, have a point of view, please send it to us. If not, do subscribe here: https://theprint.in/subscribe/

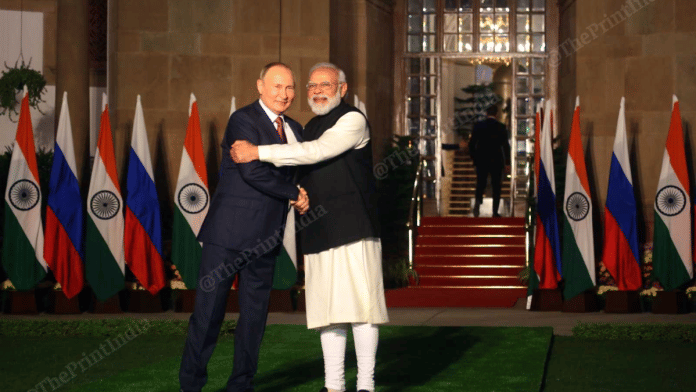

Does Modi not injure India’s international image by excluding the Opposition from the President’s formal function to welcome Vladimir Putin? This was not a minor oversight; it was a deliberate political act, one that reduced the stature of the Indian state in the eyes of the world. If anyone’s image lies in shambles after this episode, it is India’s — not Putin’s. A statesman as seasoned as Putin, accustomed to reading political atmospheres with precision, would certainly have noticed the insecurity that drove such an exclusion.

Rahul Gandhi’s presence would have added class and composure. Mallikarjun Kharge’s calm dignity would have reflected the maturity of Indian parliamentary tradition. The Congress, for all its flaws and crises, has historically produced leaders of refinement and diplomatic poise. The same cannot easily be said of many in the current ruling establishment, where public rhetoric is often shrill, personalised, and lacking in statesmanlike depth.

What is at stake here is not the personality of Modi or Shah, but a long-standing principle in Indian diplomacy: foreign policy occasions are moments for national unity, not partisan display. India has always understood that when a foreign head of state arrives, the nation must appear as one. Even in times of intense domestic turbulence — Indira Gandhi’s post-Emergency phase, the bitter coalition years of the 1990s, or the fragile UPA years — governments ensured that the Opposition was never excluded from state receptions.

The reason was simple and wise: do not wash domestic disputes before foreign guests. This was an unwritten constitutional ethic, a quiet ideal shared by all parties. The Republic’s prestige was a collective responsibility.

When Nelson Mandela visited India, leaders across the spectrum stood together. When Bill Clinton arrived in 2000, the Opposition was invited to every major ceremonial event. Barack Obama’s two visits saw broad political inclusion. Even adversarial leaders — Iranian presidents, Chinese premiers, Pakistani heads of state — were received with dignity that transcended party divisions. This wasn’t generosity. It was protocol, principle, and the confidence of a nation comfortable in its democratic skin.

By breaking with this tradition, the current government has revealed more about itself than about the Opposition. Modi and Shah’s insecurity is not simply personal; it is institutional. It stems from an inability to tolerate parity, dignity, or even the symbolic presence of political rivals. Such small-mindedness might satisfy party loyalists, but it diminishes India’s authority as a democratic power.

A confident leader would have welcomed the Opposition to the ceremony, demonstrating that India’s foreign policy stands above domestic rivalries. A mature leader would have understood that the presence of Rahul Gandhi and Kharge would enhance the ceremony, not undermine it. Their inclusion would signal to Putin — and the world — that India’s democracy, though noisy, is whole; that it is capable of unity in moments of state significance.

Instead, the government chose to project a brittle, partisan version of India. The message it sent was unfortunate: that India is unable to separate the nation from the ruling party; that the government does not trust its own democratic institutions enough to share ceremonial space; that protocol can be bent to soothe insecurities rather than uphold dignity.

There was dignity to offer to Putin, and India failed to offer it. If anything, the exclusion cast a shadow over the visit. It made the event look less like a national welcome and more like a party rally hiding behind the façade of state power. What could have been an occasion of collective pride became a symbol of democratic erosion.

India has lost more than face. It has lost the opportunity to project itself as a nation that honours its constitutional offices with the gravitas they deserve. Rashtrapati Bhavan is not an extension of the Prime Minister’s Office. It is the ceremonial heart of the Republic, meant to rise above political winds. When the President hosts a foreign head of state, the entire political spectrum is expected to stand together.

The government’s choice to exclude the Opposition has chipped away at that idea. It has made India appear smaller, insecure, and less confident in its own pluralism. And irony walks close behind: the attempt to belittle the Opposition has, instead, belittled the nation.

In the end, India has diminished itself. Not because the Opposition was missing from the room, but because the government could not rise above its own fears. A state that confuses party with nation exposes the limits of its leadership — and reveals its deepest inadequacies on the global stage.

These pieces are being published as they have been received – they have not been edited/fact-checked by ThePrint.