Peter Mandelson’s ties with disgraced financier Jeffrey Epstein should trigger a reckoning for Britain’s House of Lords. The legitimacy of the 700-year-old second legislative chamber rests heavily on tradition, with members wearing scarlet-and-white ermine robes on ceremonial occasions and referring to each other as “my noble lord” or “the noble baroness.” Seeing a peer of the realm pictured in his underwear in the house of a pedophile sex-trafficker tends to undercut the mystique. The disconnect is becoming untenable.

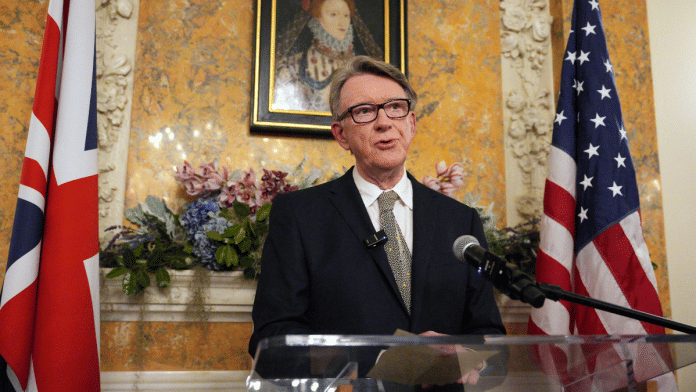

Mandelson, facing a police investigation for passing internal government communications to Epstein during the global financial crisis, bowed to pressure to resign from the House of Lords on Tuesday. The 72-year-old remains a peer, though, and can only be stripped of that title by act of parliament — a route that hasn’t been used for more than a century. Contrast that with the speed with which King Charles III denuded his brother Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor of his royal prerogatives and associated titles when the former Duke of York’s associations with Epstein became too much for “The Firm” to bear, and the problem becomes glaringly apparent.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who had urged Mandelson to step down, has called on other parties to cooperate in modernizing the house’s disciplinary procedures. But that’s only half the job. It addresses how to deal with rogue peers, not how they enter the institution in the first place. This is arguably the more gaping hole.

There are many aspects of the House of Lords that merit scrutiny; reform of the chamber is a perennial public policy topic, and calls for its abolition come regularly. Labour promised “immediate” change in its manifesto for the 2024 election, saying among other things that it would remove the rump of hereditary peers who still have rights to sit in the house and vote, impose a mandatory retirement age of 80 and change the appointments process to “ensure the quality” of new entrants. It hasn’t followed through.

The task is only growing more urgent. This isn’t a case of a single bad apple. Mandelson’s example may be uniquely damaging both because of his political stature, as a Labour Party grandee who held multiple cabinet positions over a decades-long career, and the nature of the allegations generated by the Epstein files (which raise questions about whose interests the then-business secretary was serving). But he is hardly alone. Misconduct scandals and controversies over questionable appointments have peppered the recent history of the House of Lords.

These have often involved the intersection of money and politics, from the cash-for-honors affair of the 2000s to the cash-for-influence scandal of the following decade, which resulted in some nominations being blocked and peers suspended. More recently, Conservative Prime Minister Boris Johnson drew controversy for several appointments — including Evgeny Lebedev, the son of a former KGB agent; party donor Peter Cruddas, ennobled against the advice of the independent House of Lords Appointments Commission; and Charlotte Owen who, at 29, became the youngest person to be made a life peer at the time of her 2023 elevation. Michelle Mone, appointed by David Cameron in 2015, is currently on leave of absence from the House of Lords after being embroiled in allegations of cronyism over pandemic personal protective equipment supply contracts (she denies wrongdoing).

Individual judgments can be questioned. Starmer has drawn deserved heat for appointing Mandelson as ambassador to the US despite all the evidence of his unsuitability (only to fire him last year after the initial disclosures of the depth of his relationship with Epstein). That criticism might also be extended to former Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown, who made Mandelson a life peer in 2008 after he had twice stepped down from ministerial positions in circumstances that raised questions about his judgment and propriety. The same might be said of the 1992 ennoblement of Jeffrey Archer, the former Conservative Party deputy chairman, who was sentenced to four years in prison in 2001 for perjury and perverting the course of justice after lying about his contact with a prostitute in a highly publicized 1980s libel trial.

Better decisions might have been made. But the persistence of scandal and controversy embracing both main political parties argues strongly that this is at root a systemic issue. As long as prime ministers have the power to bestow peerages as they see fit, the temptation will be there to dispense them as political favors and rewards rather than on merit. The obvious answer is to outsource this task to an independent body that would properly vet prospective appointees — as, among others, Meg Russell, a professor at University College London who has written two books on the House of Lords, and the anti-corruption group Transparency International have recommended.

Such a body already exists — the appointments commission. It performs a vetting function for nonaligned peers but prime ministers are free to disregard its advice in the case of party-political nominations, as Boris Johnson did in the case of Cruddas. Canada, whose all-appointed upper chamber was modeled on the House of Lords, moved the candidate identification process to the non-partisan Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments in 2016. That change retains strong public approval.

The House of Lords does important work in giving detailed and often expert scrutiny to legislation in a more reflective and less partisan atmosphere. But public confidence in an unelected chamber is dependent on the idea that its members are indeed “noble” — raised to the elite because of their exceptional qualities of selfless public service, expertise, integrity or other attributes. Scandals that appear to show peers are just as susceptible to vice as the ordinary citizenry may make the commoners feel they are watching a cynical charade. That’s a dangerous road to go down.

This report is auto-generated from Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.