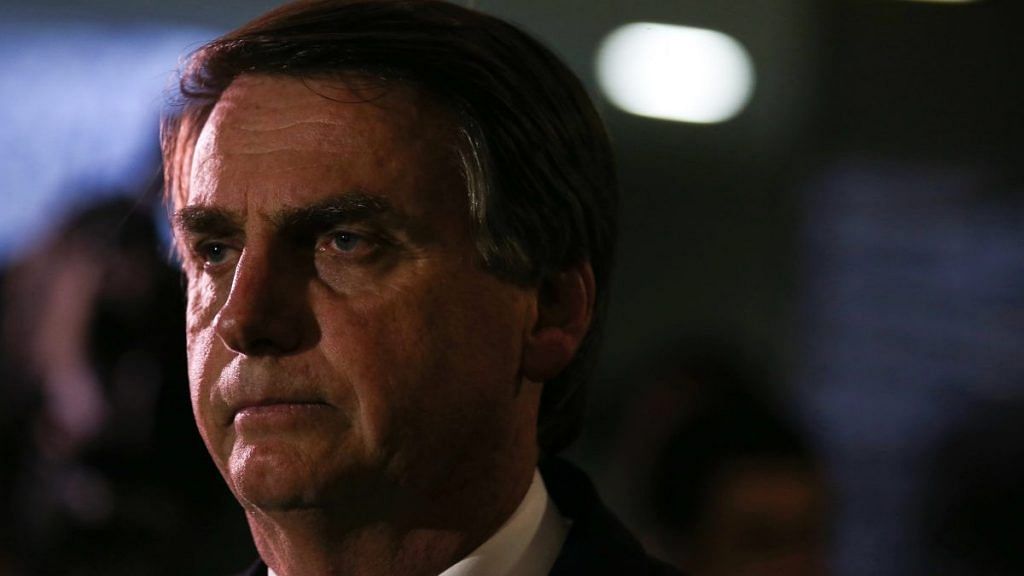

New Delhi: When Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro accepted India’s invitation earlier this week to be a chief guest at the upcoming 71st Republic Day, the Narendra Modi government was faced with some acerbic criticism.

While some argued that New Delhi was inviting a “far-Right bigot” for the celebrations, others said the government was repeating a its “mistake” of calling a group of largely Right-wing European parliamentarians to visit Jammu and Kashmir recently.

Critics of the central government’s decision also have a robust set of evidence to back their claims.

In 1999, Bolsonaro had called for the assassination of former Brazilian president Fernando Henrique Cardoso. Again, in 2003, he had told a fellow female legislator that he won’t rape her because she “doesn’t deserve it”.

His offensive comments have been steadfast. In 2011, Bolsonaro said he would rather have his son die in an accident than come out as a homosexual. And as recently as 2017, the president had remarked that “a policeman who doesn’t kill isn’t a policeman”.

Such statements have also created an impression that Bolsonaro is part of the global nationalist-populist wave. But to look at him from such as lens is only a reductive exercise.

“The Bolsonaros (Jair and his sons) are above all a Brazilian phenomenon, a product of not only the country’s severe economic, institutional and criminal crises since 2014, but also of its successes in the decade prior,” wrote Brian Winter, editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly.

Also read: Amazon forest is reaching its tipping point, world needs to scale solutions

A magazine article and Bolsonaro’s imprisonment

Bolsonaro joined the military in 1973 and slowly rose up the ranks. One of his commanding officers had earlier described him as having “excessive financial ambition…lacking logic, rationality and balance”.

But the perception that Bolsonaro thinks like a common man on the street did later pay him a lot of political dividends.

Almost a decade after joining the military, he rose to fame in 1986 after writing an article in the country’s prestigious magazine Veja. In the piece, he berated about low military salaries. Bolsonaro was subsequently imprisoned for 15 days but this jail term helped kick-start his political career.

By 1989, he was elected to the city council of Rio and became a congressman (legislator) by 1991. In the next two-decades-and-a-half, Bolsonaro spent his time in political wilderness. His rhetoric, often laced with bigotry and homophobia, earned him the reputation of a radical conservative. But he mattered little in Brazil’s mainstream politics.

In as recently as 2017, when he contested the elections for the post of speaker in Brazil’s lower house, Bolsonaro managed to get only four votes.

The country was, until that time, ruled by Left-wing parties and space for Right-wing ideologues were rather limited. But things quickly changed and he was elected Brazil’s president in January 2019.

Also read: Modi govt’s Kashmir crackdown is damaging India’s image abroad

Brazil after the Petrobras scandal

Like many nations, Brazil too felt the impact of the 2008 global financial crisis and its economy had dramatically slowed down. A few years later, in 2014, the nation was hit by its largest corruption scandal ever, involving the petroleum giant Petrobras.

The scandal shook the very foundations of Brazilian politics when dozens of leaders and high-level businesspersons were indicted. Widespread investigation revealed that Petrobras officials had received millions of dollars in kickbacks from construction companies in exchange for contracts at inflated prices. In turn, some of these funds were siphoned off to politicians who used them to buy votes.

By 2016, most of Brazil’s leading politicians, including its former president Dilma Rousseff, were found guilty of corruption and forced out of politics. When Michael Temer succeeded Rousseff, his government too was riddled with allegations of corruption and quickly lost all legitimacy.

At the same time, the country’s economy was in a complete free-fall. The unemployment rate in Brazil stood at over 12 per cent and its national health care system was collapsing. The country’s per capita income had collapsed by 10 per cent since 2014. It also had to face consistent technical recessions in the past four years.

The crime levels in the country continued to grow as well. Brazil is infamous for having 19 of the 50 most violent cities in the world. There are close to 60,000 homicides in the nation every year.

The rise of Bolsonaro

Bolsonaro had made his presidential bid in such a context — a debilitating economic condition, rising crime levels and a pervading perception that the entire political class was corrupt.

The most significant feature of his 2018 election campaign, therefore, was that he wasn’t corrupt. One of his campaign ads had Bolsonaro standing in front of a Brazilian flag that read: “Hitler, Mussolini…they call him everything but CORRUPT”.

Bolsonaro emerged as the candidate who would maintain law and order — linking corruption with street crimes and promising more jobs for young Brazilians. He talked about increasing gun ownership, giving the police a free-hand to kill suspected criminals and longer sentences for those found guilty.

He also reached out to Brazil’s business community and its foreign investors. He promised to cut the size of its government and unleash the country’s greatest free-market revolution.

President Bolsonaro: Part-reform, part-identity politics

Since getting elected, Bolsonaro’s term, however, has been far from non-controversial.

He had a major diplomatic row with France’s President Emmanuel Macron over the razing Amazon forest fires. Bolsonaro has also unleashed a culture war that is rampant with identity politics.

“He has repeatedly slammed cultural Marxism, gender ideology and environmental psychoses’ over accelerating deforestation. ‘We are going to get rid of all this crap in Brazil — crap that is corrupt and communist,’ he said last week (August 2019),” noted a feature in The Financial Times.

Bolsonaro has chosen Paulo Guedes — a former student of Milton Freedman, the patron of free-market economics — as the country’s finance minister to spearhead his agenda of transforming Brazil’s economy.

But in spite of massive government-funded welfare programmes, Brazil continues to have a very large and inefficient public sector. It leaves the government with no real fiscal space to make any long-term investments in the nation’s economy.

Last month, Bolsonaro and Guedes succeeded in getting their significant pension-reforms through the country’s legislature. This reform would substantially cut the government’s spending on pensions, giving it some much-needed fiscal space.

Guedes has proposed more reforms that could see the government privatise inefficient public enterprises, rationalise government subsidies and major tax reforms. But without a parliamentary majority, it is hard to get legislative approval for these economic reforms.

Moreover, it would take a long period before the Brazilian economy can reap the benefits from Bolsonaro’s transformative economic agenda. Until then, Bolsonaro has decided to deploy identity politics and keep the pot stirring.

Also read: Brazil’s president wants to deforest the Amazon, and the UN has few options to stop him