Cities are, quite literally, built on sand. As global urbanization continues apace, the demand for concrete (and the sand that goes into it) increases.

By 2100, it’s estimated that up to 23% of the world’s population – a projected 2.3 billion people – will be living in the 101 largest cities.

But to house those people, industrial sand mining or aggregate extraction – where sand and gravel are removed from river beds, lakes, the oceans and beaches for use in construction – is happening at a rate faster than the materials can be renewed, which is having a huge impact on the environment.

How big is the problem?

Estimates suggest that between 32 and 50 billion tonnes of aggregate (sand and gravel) are extracted from the Earth each year, according to a report from the WWF, making it the most mined material in the world.

In 2012 alone, the UNEP estimates enough concrete was created to build a wall around the equator measuring 27 metres high by 27 metres wide.

While around a third of the planet’s land surface area is made up of desert, it’s the wrong kind of sand for the construction industry, because the particles are rounded by the wind and don’t bind together in cement and concrete as well as the more angular particles found in river beds and lakes. Ironically, Dubai is importing sand from Australia to keep up with its building needs.

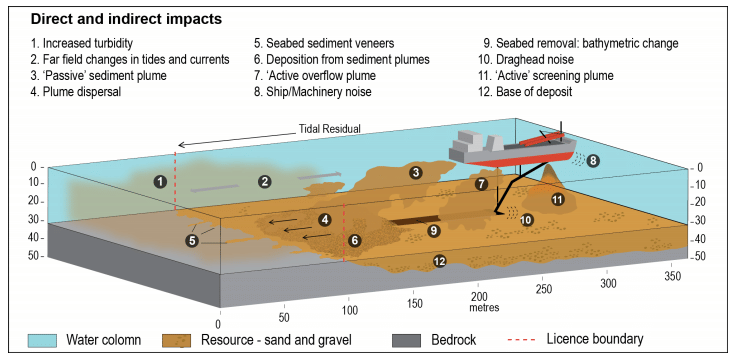

Direct and indirect impacts of aggregates dredging on the marine environment. Image: UNEP

According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), sand mining of river deltas, such as the Yangtze and Mekong, is increasing the risk of climate-related disasters, because there’s not enough sediment to protect against flooding.

“Keeping sand in the rivers is the best adaptation to climate change,” the WWF’s Marc Goichot told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. “If a river delta receives enough sediment, it builds itself above sea level in a natural reaction.”

Sand for Singapore

Besides being used to build roads and cities, sand is also used in land reclamation – which is happening apace in Singapore.

By 2030, the island nation wants to become almost 500 square kilometres and has grown by almost a quarter since it became independent in 1965.

Such has been Singapore’s demand for sand, it’s become the world’s largest importer. Much of its sand has come from the Indonesian archipelago, where at least 24 islands, as well as the ecosystems they contained, have disappeared since 2005 due to mining.

In 2007, Indonesia banned sand exports to Singapore, after Malaysia did the same in 1997. Last year, Cambodia imposed a permanent ban on sand exports because of its impact on the environment.

The world’s biggest sand mine

Sand mining is also big business in China, which is undergoing rapid urbanization. The population of its financial centre Shanghai alone has exploded in the past two decades, growing by 7 million since 2000.

Sand mining is also big business in China, which is undergoing rapid urbanization. The population of its financial centre Shanghai alone has exploded in the past two decades, growing by 7 million since 2000.

In 2000, illegal sand mining along the lower and middle reaches of the Yangtze River was banned because erosion was creating a threat of flooding to local populations, barges were causing accidents and armed gangs were clashing with police.

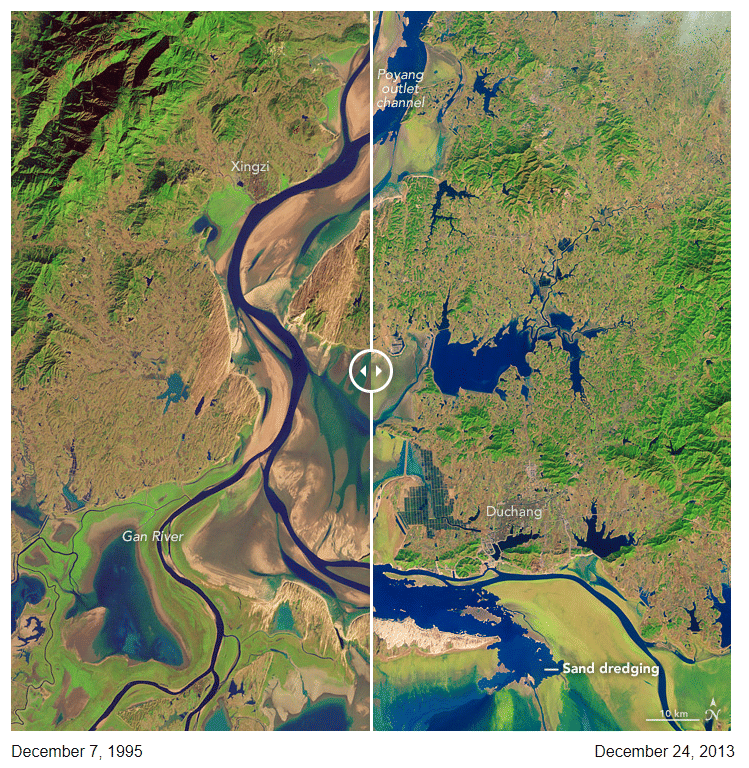

However, the ban meant miners moved 600 kilometres upstream of Shanghai to Poyang Lake, which flows into the Yangtze and is home to endangered waterbirds, including Siberian cranes and Oriental White Storks, as well as freshwater porpoise.

Using data collected by NASA’s Terra satellite, researchers found the lake was producing as much as 236 million cubic metres of sand a year – 9% of China’s total output – which the WWF says makes it the world’s biggest sand mine.

James Burnham, an ecologist with the University of Wisconsin and the International Crane Foundation, said: “Sand mining has compromised the ecological integrity of the lake by contributing to less predictable seasonal water fluctuations and to a series of recent low water events.”

Studies have also found the sediment stirred up by the mining, as well as the noise from boats, interferes with the porpoises’ sonar, so they cannot locate food.

Coastal erosion in California

Sand mining also happens in the Western world. In July 2017, it was announced that the last coastal sand mine in the US would close within three years, following protests from environmentalists over the erosion of California’s beaches.

What can be done?

While pressure on governments to regulate sand mining is increasing, more needs to be done to find alternatives for use in construction and for solving the world’s continuing housing crises.

In its 2014 report, Sand, Rarer Than One Thinks, the UNEP Global Environment Alert Service suggests optimizing the use of existing buildings and infrastructure, as well as using recycled concrete rubble and quarry dust instead of sand.

Breaking the reliance on concrete as the go-to material for building houses, by increasing the tax on aggregate extraction, training architects and engineers, and looking to alternative materials such as wood and straw, would also reduce our demand for sand.

This article was first published in the World Economic Forum.

Kate Whiting is a senior writer of Formative Content.