A rising voice in Dutch politics is capturing part of the country’s far-right base, loosening anti-migration leader Geert Wilders’ grip on voters ahead of Wednesday’s election.

Ingrid Coenradie, a little-known politician until recently, is leading the charge, transforming her tiny JA21 party into a budding conservative force by appealing to voters tired of Wilders’ hardline Freedom Party.

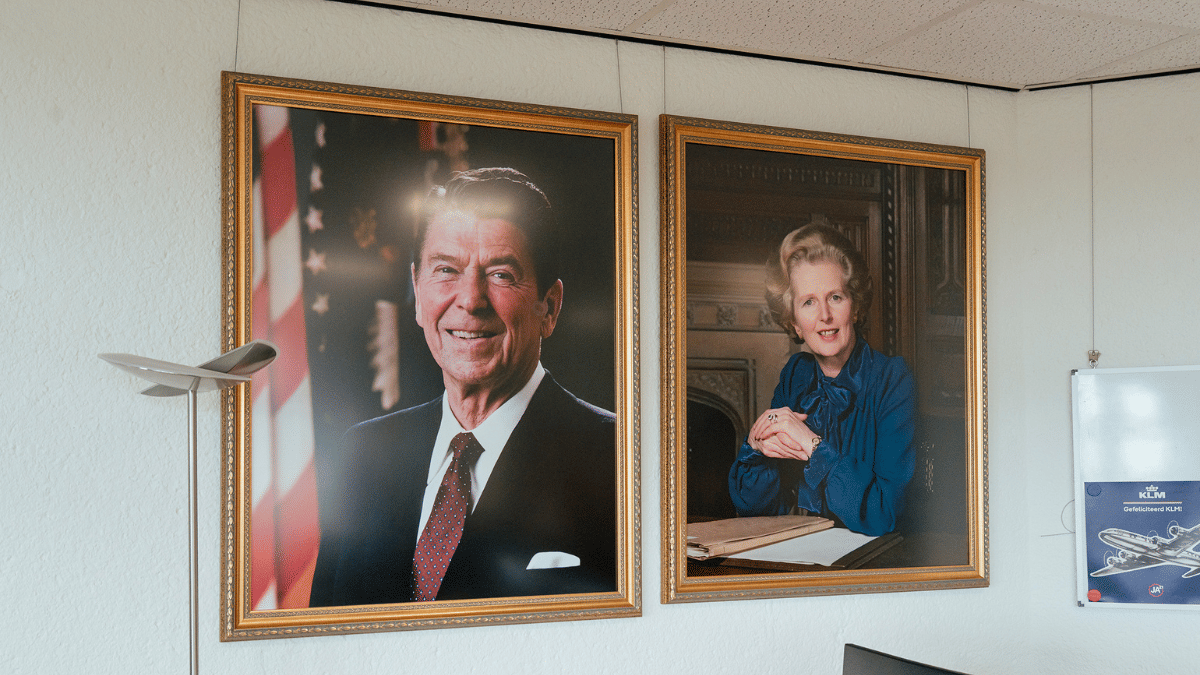

“Over the past few years, people have voted for Geert Wilders, whether out of support or protest. But now you’re seeing people drop out, disappointed,” Coenradie told Bloomberg News, sitting in her party office decorated with portraits of Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and other conservative icons.

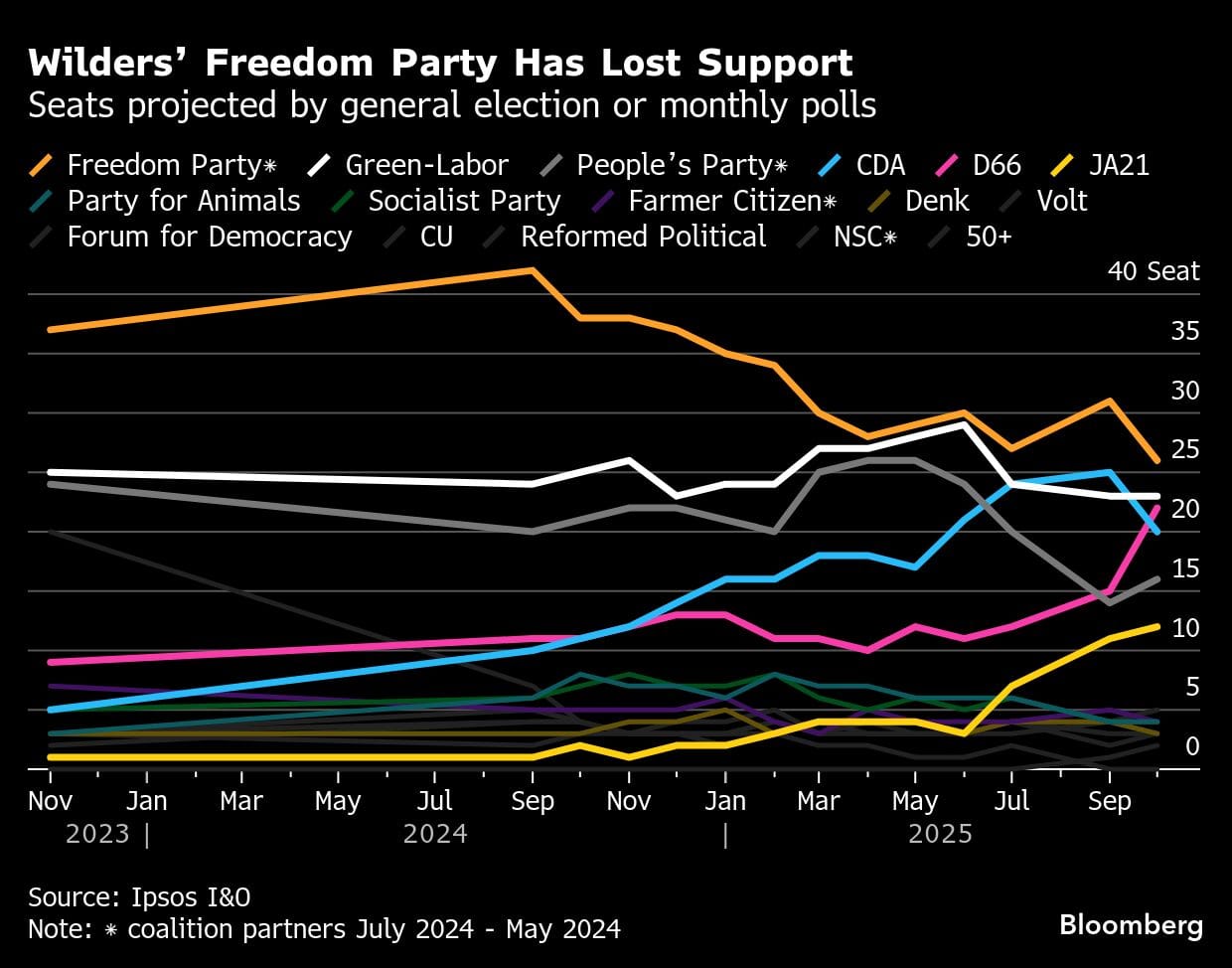

Polls show the pitch is working. JA21 now has enough support to help sway coalition talks after Wednesday’s election.

The party has done it by promising to push law-and-order policies without Wilders’ burn-it-down tactics, which helped tank the last government. JA21 still wants deep migration cuts, for instance, but shuns Wilders’ preferred ban. It’s also willing to partner with a range of groups in the splintered Dutch parliament.

That spells trouble for Wilders. Even if his party wins the election, the anti-Islam, Euroskeptic leader’s influence will most likely be diminished after, as officials jockey to form a government. He could even be sidelined altogether — replaced by a more flexible brand of right-wing politics.

“Within the far-right side of the spectrum, very large shifts are possible,” said Matthijs Rooduijn, a University of Amsterdam professor who studies populism and right-wing politics.

Wilders’ Woes

Coalitions are a necessity in Dutch politics, where clearing .67% of the vote can get you a seat in parliament.

Currently, it would take at least three parties to secure the 76-seat majority needed in parliament, according to the latest polling by Ipsos I&O Research.

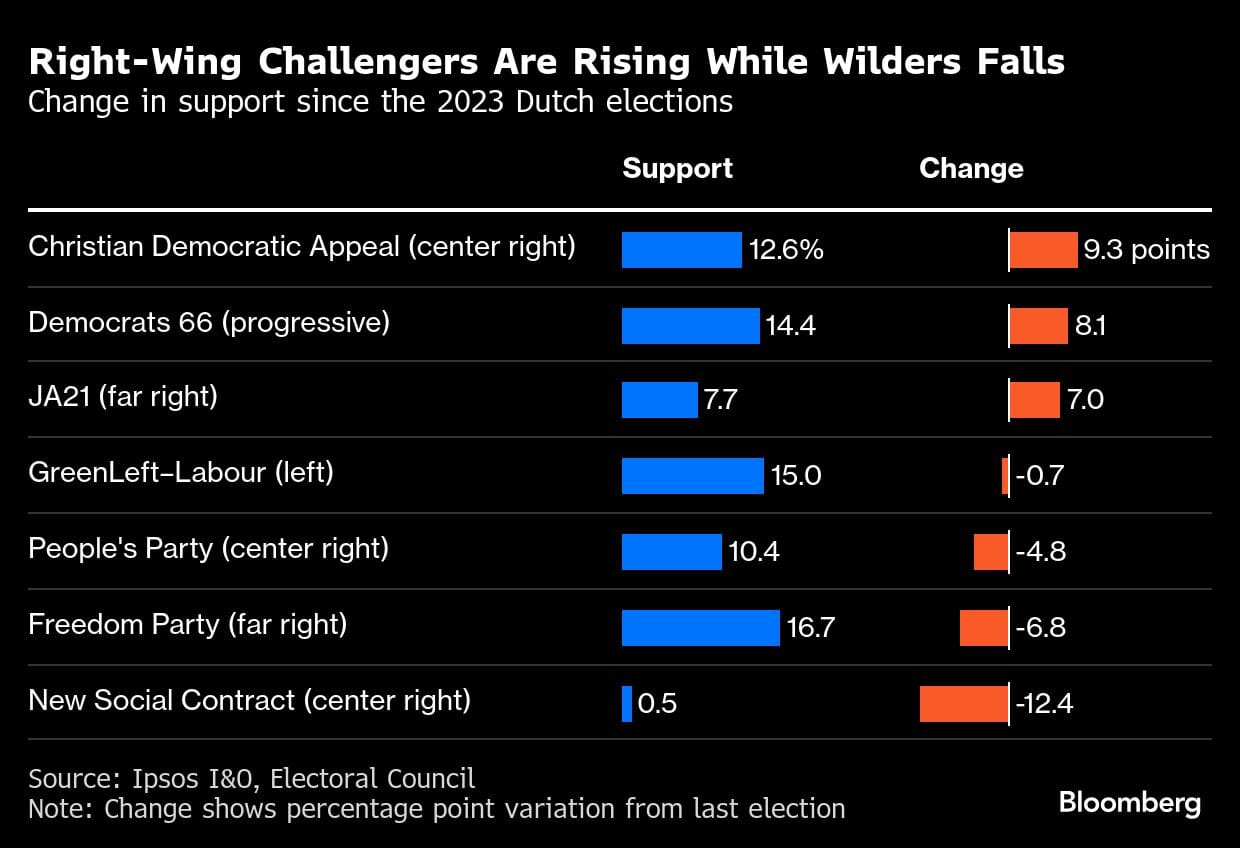

On the right, support is split.

Wilders’ Freedom Party has dropped below 17% in the latest polls, a tumble from its 33% high in 2024. Meanwhile, the center-right Christian Democrats have risen from just over 3% two years ago to nearly 13%, and JA21 has jumped from barely registering to nearly 8%.

That’s a change from the 2023 election, when Wilders’ party emerged as the clear right-wing leader and several parties did not rule out teaming up with him.

“That made the road completely open, because he did not receive a firm ‘no,’” Rooduijn said.

This time, all major parties have excluded Wilders as a coalition partner. And there’s more competition on the right.

The situation, Rooduijn said, “will now be a lot more difficult for him, with most likely no influence in the negotiations.”

That gives JA21, which is projected to grow from 1 to 12 seats, sizable leverage. The party, founded in 2020, doesn’t carry Wilders’ baggage, is preaching compromise and could help put a coalition over the top. The Christian Democrats and Freedom Party will both come courting as they spar to control the right.

JA21 says it will welcome all suitors.

“We don’t exclude anyone, that’s not how democracy works,” Coenradie said.

JA21 could, in theory, even hold the key to a right-wing coalition without Wilders. If a few centrist parties team up with the Christian Democrats and JA21, they’re only six seats short of a majority, according to the latest polls.

“It could be tough,” said Rooduijn. “But tough is very different from a firm no; time can make things very fluid in negotiations.”

Another wild-card factor: Wilders has out-performed the polls before. He could do so again, disrupting the pre-election predictions.

“Many people make their choice only on the day itself,” said Léonie de Jonge, a professor studying far-right politics at the University of Tübingen.

JA21’s Stances

Despite its odes to pragmatism, JA21’s platform is entrenched on the far right.

The party wants to expand bans on burqas and mosque prayer calls, send Syrian refugees back to “safe parts” of the country and promote “traditional Dutch culture.” It supports pouring money into the police while installing an Elon Musk-inspired efficiency minister to find cuts elsewhere. And within Europe, JA21 wants to erect border checks with Germany and Belgium and slash European Union regulations.

On economic policies, however, JA21 trends more liberal than the Freedom Party, backing higher personal contributions to medical care, for instance.

It’s also slightly less hardline on immigration than the Freedom Party. Wilders’ party wants to use emergency laws to end asylum, ban family reunification migration and abandon the United Nations Refugee Convention, which outlines rights and legal protections for people fleeing danger. JA21 is instead calling to “modernize” the convention and “sharpen” reunification policy, without shutting down the process altogether.

Coenradie argued that such distinctions show JA21 can help incrementally advance conservative priorities.

The Freedom Party “sometimes has a tendency to lump everything together,” she said. “But if you really want to make progress toward a solution, you will also have to unravel things and take a closer look.”

Of course, vowing to compromise is easier than actually compromising — and JA21 does have stances that would test its stated pragmatism.

In addition to its strict immigration platform, JA21’s energy policy may ruffle feathers with the Christian Democrats and centrist parties. Specifically, JA21 is pushing to reopen Europe’s largest gasfield, which the government closed due to earthquake fears. The others want to keep it shuttered.

Fiscal policy is another contentious subject. The Christian Democrats, for instance, are open to issuing eurobonds — essentially taking on joint debt — to help Europe pay for a massive rearmament plan. JA21 rejects any shared debt plan.

Coenradie refused to label the issue a deal-breaker.

“If we want to move forward, if we want to make the country better, it’s not about the differences,” she said. “It’s about how we find common ground together.”

Quick Rise

Until earlier this year, Coenradie was actually a Freedom Party minister, serving in a coalition government that included Wilders’ party.

But only months into her job, Coenradie clashed publicly with Wilders over her proposal to address a prison shortage. She wanted slightly shorter sentences. Wilders wouldn’t budge.

“She received enormous praise for contradicting Wilders, which no one else dared to do,” said de Jonge, the University of Tübingen professor. “In a completely amateurish and incompetent cabinet, she was the only Freedom Party minister who showed any backbone and competence on her portfolio.”

The move turbocharged her career. After Wilders toppled the government in June, Coenradie quit and joined JA21, pulling attention to the smallest party in parliament, headed by Joost Eerdmans. JA21 quickly jumped from three to nine projected seats in the polls — dubbed the “Coenradie effect.”

Now, JA21 is insisting it represents the future of Dutch right-wing politics.

“People still want to move to the right, but who’s going to make that happen?” Coenradie said. “That’s where JA21 comes in.”

(Reporting by Patrick Van Oosterom)

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.

Also Read: EU pledges continued financial aid to Ukraine through 2027, says Zelenskyy