Singapore: When US President Donald Trump talks about the need for a “big, beautiful trade deal” because of the nation’s trade deficits with many countries, and alleges that the US faces unfair trade, the question that needs to be asked is whether today’s trade imbalances are unique in history. How do current patterns of global surpluses or deficits and foreign wealth accumulation compare with those of the past?

To bring new answers to these core questions, two economists, Gaston Nievas and Thomas Piketty, have pieced together a new database on global trade flows and the world balance of payments covering the period 1800 to 2025.

A trade deficit occurs when a country imports more goods and services than it exports while balance of payments is a record of all economic transactions between residents of a country and the rest of the world during a specific period.

Their research, based on the historical balance of payments constructed from various data sources, aims at understanding the historical pattern of trade and financial imbalances over the years, and was published as a working paper in May this year by World Inequality Lab, a Paris-based research centre dedicated to studying inequality and its impact on public policies.

In it, the economists examine the patterns of global imbalances from 1800 to 1914 as one globalisation period and 1970 to 2025 as the other, and find some striking similarities and unique differences as well.

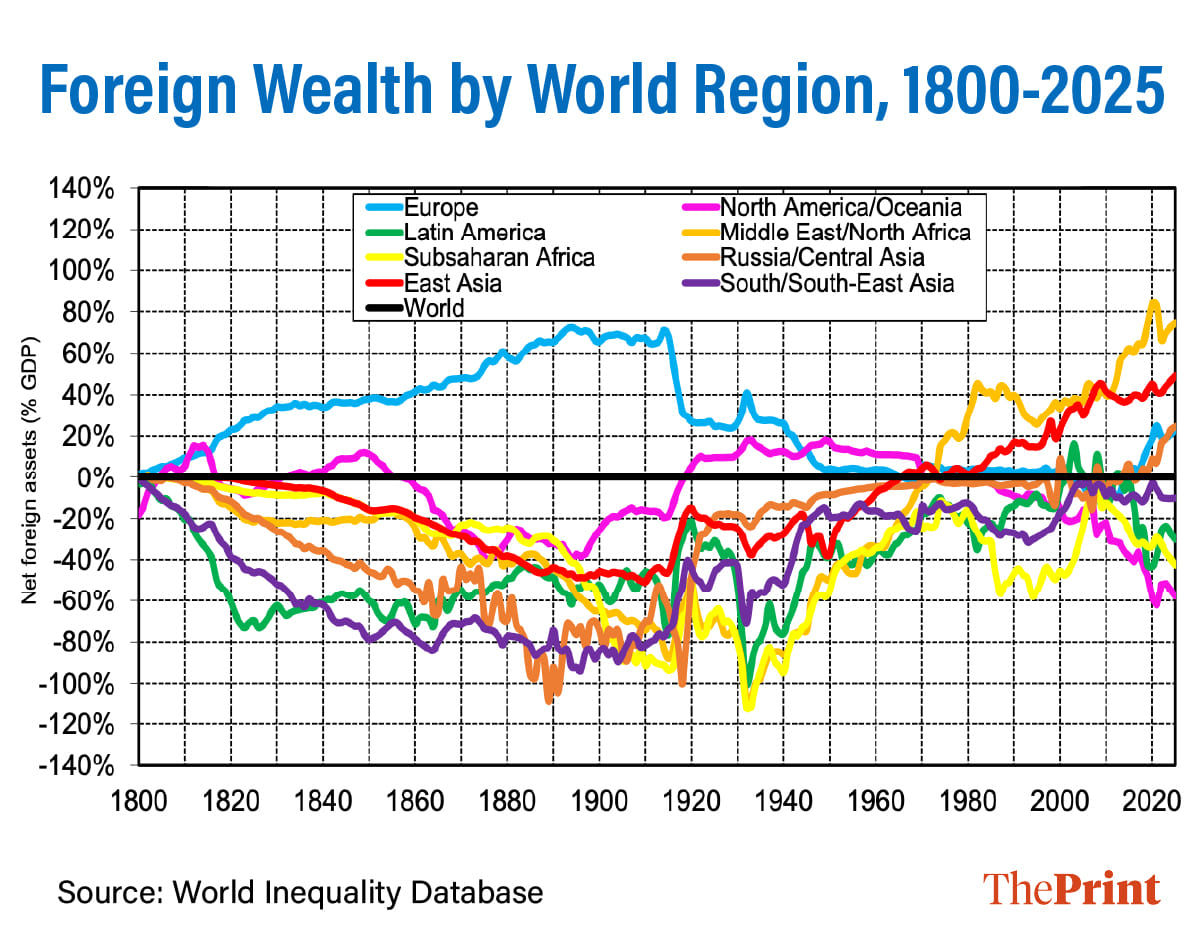

Between 1800 and 1914, Europe owned a good chunk of the rest of the world without having a trade surplus. On the eve of World War I, its foreign wealth, i.e., net foreign assets owned by European residents in the rest of the world, reached about 70 percent of Europe’s GDP (30 percent of world GDP), while all other parts of the world had a net foreign debt.

Interestingly, between 1914 and 1950, Europe’s foreign assets vanished and were replaced by foreign assets owned by the US between 1920 and 1970, and later by oil countries, and especially by East Asia (China and Japan), since the 1970s-1980s.

By 2025, the magnitude of foreign wealth ownership seems to resemble a level comparable to that observed in 1914, but with a very different geography of lender and borrower regions.

The two peaks (1914 peak and 2025 peak) in foreign wealth positions, i.e., countries owning assets in other countries, are also different in many ways. The magnitude of the 1914 peak was much larger than the 2025 peak, especially if we consider the fact that only a subset of the core European powers (Britain, France, Germany, Netherlands) held substantial positive foreign wealth, while the rest of Europe owed money.

“An even more striking difference between the two peaks is that Europe was able to build a very large foreign wealth without ever running trade surpluses over the entire 1800-1914 period,” the authors note in their paper.

For Europe, there was rather an enormous trade deficit for primary commodities like agricultural products, minerals etc. (as large as 3.5-4 percent of world GDP each year between 1860 and 1914), and a large but insufficient trade surplus for manufacturing goods (about 2-2.5 percent of world GDP on average over the same period).

This indicates that while Europe was the manufacturing powerhouse in the 19th century and early 20th century, making large trade surpluses by exporting its manufacturing products (e.g. British textiles), these trade surpluses were a lot smaller than the deficits in the primary commodities. This means Europe was importing a lot of primary commodities for its consumption (such as foodstuff) and that a large part of its manufacturing output, using primary imports from the rest of the world such as cotton, wood, minerals, etc, was devoted to domestic consumption and investment.

So, how did Europe have a large and permanent trade deficit in primary commodities over the 1800-1914 period yet built large foreign wealth.

The answer lies in observing the invisible flows of Europe’s balance of payments–trade in services, foreign income, and foreign transfers, which all show a positive European surplus.

To quote from the paper: “The main European powers are receiving during this period enormous flows of dividends, interest, royalties and profits from the rest of the world, and these are the flows which allow them not only to pay for their trade deficits but also to generate large current account surpluses and to keep accumulating foreign wealth in the rest of the world.”

“It should be noted that no country or region in the world has ever received foreign income inflows approaching this magnitude since then.”

Also Read: Trump extends deadlines for trade deals to 1 August, takes swipe at allies Japan & South Korea

Colonial extraction

During the 1800-1914 period, foreign transfers flowed from south and north and mostly consisted of colonial transfers towards Europe, one example being the debt imposed by France on Haiti in 1825, and most importantly, permanent public and private transfers of tax revenue from colonies to the metropolis (especially from India to Britain and Indonesia to the Netherlands).

Haiti in 1825 agreed to pay an indemnity of 150 million gold francs to the European power which was meant to compensate French plantation owners for “lost property” following independence, but the amount far exceeded actual losses.

A large part of Europe’s total foreign income inflow over this period corresponds to what is identified as “excess yield”, i.e., wealth accumulated due to the differential between rate of return on gross foreign assets and gross foreign liabilities. This means that the countries that control the dominant currency and the leading financial institutions of the time can borrow at lower rates and obtain high returns on their foreign investments.

Although these patterns of “excess yield”, positive and negative incomes play a very important role, the point is that they are not large enough to reverse the trade patterns in the current scenario.

This is the key difference between the “Pax Britannica” of the 1800-1914 period and the “Pax Americana” of the 1970-2025 period. The first refers to a period of relative peace and stability in Europe and the world, primarily during the 19th century when the British empire was the dominant global power. The second refers to a period of relative peace, particularly in the western hemisphere and globally, following World War II, largely influenced by US dominance as a global superpower.

In the first period, Europe could appropriate large foreign transfers and income flows from the rest of the world, to be able to transform large trade deficits and accumulate massive foreign wealth. In the second period, while the US, through its financial dominance, appropriated sizable “excess yield”, this wasn’t enough to offset the trade deficit.

The researchers say this explains the “nervousness and aggression” of the US administration in 2025, in which Trump seems to believe that the global public good provided by “Pax Americana” should be better rewarded by the rest of the world, through financial transfer by allies in compensation for military spending or direct appropriation of mineral resources and other assets in Greenland, Ukraine or elsewhere.

The challenge they face is that the rest of the world does not appear to be entering a new colonial era compared to that observed during the 1800-1914 period.

Another part of the economists’ research looks at alternative development trajectories by running certain simulations. These simulations illustrate the role of power relations and bargaining power in global imbalances: relatively small changes in terms of exchange can make enormous differences in long-run outcomes.

“In effect, without the colonial transfers, and in particular without the colonial transfers of the early 19th century, the geography of wealth would be radically different in 1914: South & South-East Asia – and to a lesser extent Latin America – would own large assets in Europe rather than the opposite. In particular, India and Indonesia would own large parts of Britain and the Netherlands,” note the economists.

Akshaya Prakash is an alumna of ThePrint School of Journalism, currently interning with ThePrint.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: BRICS leaders slam Trump tariffs & unilateral sanctions, US President promises additional tariffs

Thomas Piketty is not an economist. He is a propagandist. A woke Left “intellectual” whose objective is to make everyone of us equally poor, and therefore, equals.