New Delhi: Miscalculation, misinformation and misperceptions in the fall of 1962 almost brought the two superpowers of the time, the US and the USSR, to the brink of nuclear conflict, as the sandy beaches of Cuba became home to a mini-arsenal of Soviet weaponry.

It was on 16 October, 1962, when McGeorge Bundy, National Security Adviser (NSA) to then US President John F. Kennedy (JFK) walked into the White House armed with ‘proof’ of Soviet missile deployment in Cuba. The Caribbean island nation had just a few years earlier witnessed a revolution, which brought Communism to the Western Hemisphere.

Bundy’s ‘proof’ set off alarm bells across the Kennedy administration. Any aggressive action could have led to the potential eruption of a thermonuclear war not just in the Caribbean but in Berlin or even Turkey, Adlai E. Stevenson, US’s Permanent Representative to the UN, warned Kennedy on 17 October.

This was the height of the Cold War. What followed was the ‘Cuban missile crisis’.

As the theory goes, in July 1962, USSR Premier Nikita Khrushchev struck a secret accord with Fidel Castro, the Communist revolutionary who led the movement that toppled the American-backed government of Cuba, to place Soviet missiles in the Caribbean nation.

Castro had emerged as a larger-than-life figure of anti-Americanism in the US’s own backyard.

In April 1961, he thwarted an attempt by Kennedy to land Cuban exiles in what is remembered as the ‘Bay of Pigs Invasion’. While the Americans saw Castro as a threat, Khrushchev saw an opportunity to deploy Soviet missiles right under the US’s nose.

Over the years many scholars have pointed out that Khrushchev had multiple incentives to use Cuba as a staging ground.

Walt Rostow, an economist and former NSA, summarises these points in his book, The Diffusion of Power, where he refers to it as Khrushchev’s attempt to enhance his political prestige, highlight his importance in the international Communist movement and gain leverage for future negotiations with the anti-Soviet bloc.

Serhii Plokhy notes in his book Nuclear Folly: A history of the Cuban missile crisis that the Americans were unaware of the true extent of Soviet military build-up in Cuba.

General Anatoly Gribkov, former commander of the Warsaw Pact military forces and a key planner of the USSR’s deployment in Cuba, revealed in 1992 at a conference attended by former Kennedy administration official Robert McNamara that the Soviets had managed to deploy 43,000 troops to the Caribbean nation by the end of the summer of 1962.

McNamara, JFK’s Secretary of Defense and the then US administration believed that there were no more than 10,000 Soviet troops on Cuban soil.

Moreover, according to Plokhy, Gribkov claimed that not only did the USSR provide Cuba with anti-aircraft weaponry, bombers and medium-range missiles capable of striking the US, but also tactical nuclear weapons.

Soviet records refer to the ‘Cuban missile crisis’ as the ‘Caribbean crisis’ of 1962.

Analysis of the Soviet reason for the deployment relies upon Khrushchev’s ‘unofficial but authenticated memoir’. The USSR Premier recalls that the idea came to him during a visit to Bulgaria in May 1962. It was intensified by the presence of analogous American deployment across the Black Sea in Turkey, the Jupiter missiles.

Also Read: How John F Kennedy covered up a ‘quid-pro-quo’ deal with USSR that ended Cuban Missile Crisis

From Europe to Caribbean, the Cold War escalates

During the 13 days that followed the US taking note of Soviet missile deployment in Cuba on 16 October, tensity in the Oval Office reached a breaking point.

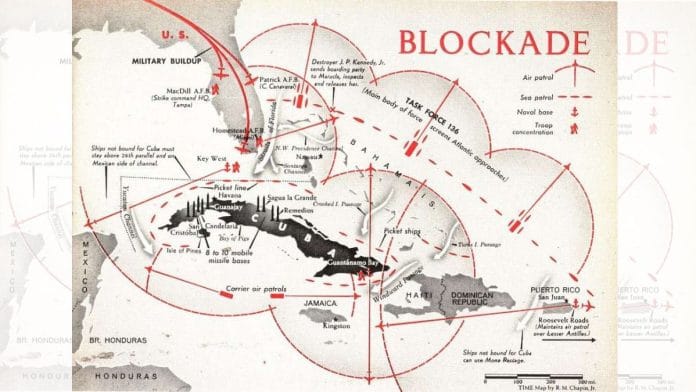

Finally, on 22 October, Kennedy went on national TV to inform the public of the developments in Cuba, and his decision of a naval “quarantine”.

It was during this speech that he famously remarked, “Our goal is not the victory of might, but the vindication of right, not peace at the expense of freedom, but both peace and freedom, here in this Hemisphere, and, we hope, around the world.”

He added: “The path we have chosen for the present is full of hazards, as all paths are, but it is the one most consistent with our character and courage as a nation and our commitments around the world. The cost of freedom is always high, and Americans have always paid for it. And one path we shall never choose, and that is the path of surrender or submission.”

Following his attempts to strike a chord with Khrushchev, Kennedy sent out the first letter to the Kremlin the very same day. In it he implored the Soviet Premier to de-escalate the situation and recalled their consensus during a meeting in Vienna. “I have not assumed that you or any other sane man would, in this nuclear age, deliberately plunge the world into war which it is crystal clear no country could win and which could only result in catastrophic consequences to the whole world, including the aggressor.”

Khrushchev wrote back to Kennedy on 23 October, calling the US naval quarantine of Cuba an “act of aggression”.

Many miscalculations were to follow before cooler heads could prevail. At one point, an agitated Kennedy told his advisers that a military offensive against Cuba was necessary.

On 26 October, ABC News correspondent John Scali informed the White House that he had been approached by a Soviet agent who told him that the USS would remove its missiles from Cuba, on the condition that the US does not invade the island. A letter from the Kremlin arrived confirming the validity of the claim, the US Office of the Historian notes.

However, on 27 October, a letter from the Kremlin heralded Soviet Union’s expectations of the removal of the Jupiter missiles from Turkey. “You have placed destructive missile weapons, which you call offensive, in Turkey, literally next to us. How then can recognition of our equal military capacities be reconciled with such unequal relations between our great states? This is irreconcilable.” Khrushchev asserted in the letter to JFK.

Later that same night, JFK’s brother Robert Kennedy, then US Attorney General, and Anatoly Dobrynin, who was then Soviet Ambassador to the US, held a clandestine meeting. Robert, according to the JFK Library, assured Dobrynin of the removal of Jupiter missiles from Turkey in this meeting.

A diplomatic thaw followed. The US furnished guarantees that it would not send troops into Cuba, and that the Jupiter missiles would be removed from Turkey. The USSR, in return, dismantled their missiles in Cuba. Crisis averted, the White House and the Kremlin also agreed to establish a hotline to facilitate direct communications, known as the “red phone”.

Ankita Thakur is an alum of ThePrint School of Journalism, currently interning with ThePrint.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Is Five Eyes destabilising India’s rise as non-white power? Idea is as old as Cold War era