New Delhi: One in every 10 adults in China identifies with ‘organised’ religion, while many adults practice ‘traditional’ religion or hold religious beliefs, a survey by American think-tank the Pew Research Center has found.

Since Pew and other non-Chinese organisations are not allowed to conduct surveys in China, the latest report analyses surveys conducted by academic groups in China. These include the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS), the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), the China Labour-force Dynamics Survey (CLDS) and the World Values Survey (WVS).

Pew also analyses reports released by China’s State Council, the National Religious Affairs Administration and data from state-run religious associations including the China Christian Council (CCC), the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM) and the Islamic Association of China.

The Pew report attempts to explain how religion in China and East Asia is distinct from religion elsewhere. According to it, in China, there is no single, literal translation of the English word ‘religion’.

The most common translation of religion in Chinese is the word zongjiao, which refers to ‘organised’ religion. The report states that China officially recognises five zongjiao, namely Buddhism, Catholicism, Islam, Protestantism and Taoism.

Also, it is important to note the term xisu, which is used to denote traditional customs and practices such as the Confucius veneration and temple festivals where folk deities are worshipped. Other key terms mentioned in the report include mixin (superstition) and xiejiao (evil cults) — both banned in China.

Xiejiao were banned in China in 1999 and have since faced intensified crackdowns by the Chinese government. Groups the government labels as xiejiao include the Falun Gong, the Children of God, the Unification Church and the World Elijah Gospel Mission Society.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is officially atheist, and no member of the party can be a member of an ‘organised’ religion. In the 1950s, as part of a “nationalisation campaign”, the government “confiscated” many temples, churches and mosques for secular use, the Pew report points out. Furthermore, religious groups were persecuted across the board — Buddhist monks for participating in a feudal regime that supported them with donations, and Christians for links to foreign missionaries and the Vatican.

Under Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976, all religious activities were banned and the Red Guards attacked and destroyed many religious sites.

The Pew report adds that after 1982, when the Chinese constitution adopted freedom of religious beliefs for ordinary Chinese citizens, religious practices started to flourish across the country, including those outside of the formally recognised religions. This freedom was enjoyed till the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, after which the government once again started suppressing religious groups outside of the official system.

In recent years, under President Xi Jinping, the government has tightened controls on Islam and Christianity, including cracking down heavily on the Muslims in the Xinjiang province of China. Even other state religions and traditions — Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism — have faced tighter scrutiny under President Xi.

Religious organisations are now expected to align their teachings and customs with Chinese traditions and pledge loyalty to the State, says the Pew report.

However, despite these efforts of the state to stamp out religion and religious beliefs, they continues to remain tenacious in China.

Also Read: Unfavourable views of China at ‘historic high’, global attitudes to Xi worsening, says Pew report

No clear evidence of rising religious affiliation

The Pew report finds no empirical survey evidence of a surge in religion in China between 2010 and now. The report also adds that it cannot firmly rule out a surge in religion, given the various sources of uncertainty.

Further, the report finds that overall in terms of zongjiao identity and practice — a narrow and relatively formal engagement with religion — the measures by various surveys have generally been stable since 2010, and seem to have decreased in some cases.

According to the 2012 CGSS, 12 per cent of Chinese adults admitted to having a religious affiliation (zongjiao). This number was 10 percent in the 2018 CGSS. Pew mentions here that the difference is within the margin of sampling error and is not statistically significant.

The CGSS 2021, on the other hand, showed a decrease in adults claiming a religious affiliation to 7 per cent. However, the 2021 survey may not be directly comparable to the earlier CGSS since it was conducted across lesser provinces and in the midst of the pandemic.

There has been a marked decline in the number of Chinese adults reporting that they are attending zongjiao activities — from 11 per cent in 2012 to 6 per cent in 2018 — the Pew survey found. It also found that among one in 10 Chinese adults who identify with a religion (zongjiao), the number of those admitting that they attended religious activities at least a few times a year fell from 53 per cent in 2012 to 45 per cent in 2018.

According to data from the 2018 WVS, only 13 per cent of Chinese adults said religion (zongjiao) was a “very important” or “rather important” part of their lives. The share of adults who say religion is very important was lowest in China at three per cent as against the 32-country median of 48 per cent, the Pew report said, citing findings of the WVS (2017-22).

Chinese spiritual beliefs more common than others

According to the 2018 CGSS, 75 per cent of Chinese adults visited the gravesites of family members at least once during the previous year. Gravesite visits in line with Chinese customs frequently involve the burning of incense and paper money and offering a drink to one’s deceased ancestor.

The 2018 CFPS also found that 47 per cent of Chinese adults believed in feng shui — a traditional Chinese practice of arranging objects and physical space to achieve harmony and ensure good luck in life. Further, the survey found that 33 per cent of Chinese adults believe in Buddha and/or bodhisattvas (Buddhist deities on the path to enlightenment).

The 2018 CGSS, however, also found that only four per cent of Chinese adults identified Buddhism as their religious belief.

As many as 26 per cent of Chinese adults burn incense for deities a few times a year or more, shows the 2016 CFPS; while, according to the 2018 CGSS, 24 per cent believe in choosing ‘auspicious days’ for special events. In addition, the 2018 CFPS found that at least 18 per cent of Chinese adults believe in a Taoist deity and 10 per cent believe in ghosts.

This discrepancy between the number of followers of organised religion and traditional customs could be attributed to the conceptual problem of applying the Western definitions of religion and measures of religious participation — such as attendance and congregational worship services — familiar to monotheistic religions of Christianity, Islam and Judaism.

But these measures are less suitable for traditional beliefs and practices of East Asia, the Pew report highlights.

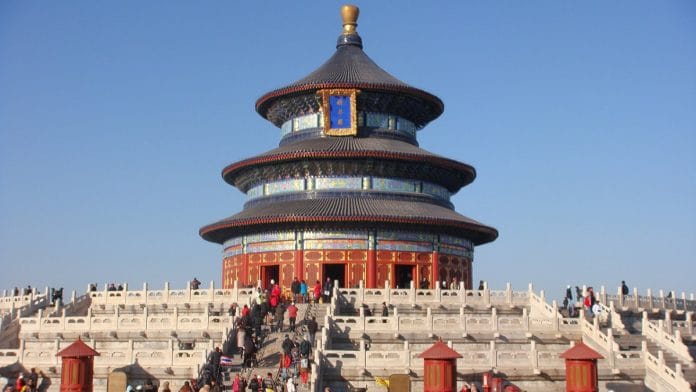

Official government statistics on places of worship, along with data on tourism at religious heritage sites show an increase for traditional Chinese religions between 2009 and 2018. In comparison, the number of officially registered Protestant and Catholic churches and Islamic mosques remained unchanged, said the Pew report.

According to the State Council Information Office (SCIO), the total number of religious sites registered with the five official religious organisations increased by 11 per cent to 1,44,000 in 2018 from around 1,30,000 in 2009 — largely due to a surge in Buddhist and Taoist temples.

Data shows that the number of official Taoist temples in China tripled from about 3,000 in 2009 to about 9,000 in 2018, while the number of Buddhist temples increased from about 20,000 to about 33,500 during the same period.

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Global public opinion of India is positive, finds new Pew survey of 23 countries