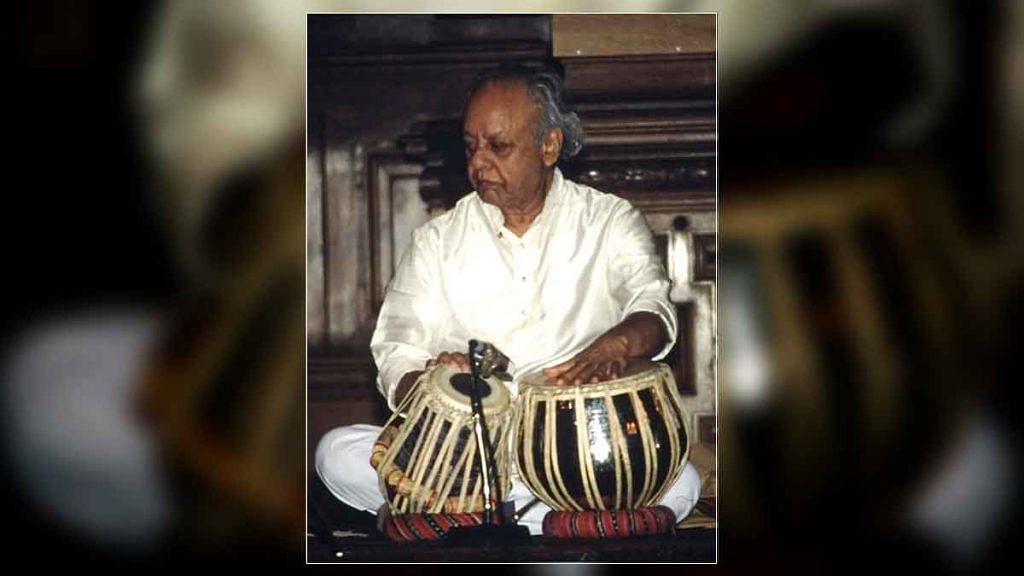

Tabla maestro Ustad Alla Rakha was one of the key figures who took Indian classical music to the West, and was also father and teacher to Ustad Zakir Hussain.

New Delhi: Pandit Ravi Shankar is usually credited as the cultural bridge between Indian classical music and the West. But would his melodic sitar be as mesmeric without the rhythmic gravitas of the tabla accompanying it?

For a large chunk of Pandit ji’s illustrious career, the tabla in question was played by Ustad Alla Rakha, who was to Indian classical percussion what Ravi Shankar was to melody — the uncrowned king. Even today, he is known among tabla enthusiasts as ‘Abba ji’, as much an acknowledgement that he was father to Ustad Zakir Hussain and Taufiq Qureshi as a doff of the hat to his own stature.

As the world observes his 19th death anniversary on 3 February, ThePrint pays tribute to the Ustad of ustads.

Conquering hearts at home

Alla Rakha was born in Ghagwal village in Jammu and Kashmir on 29 April 1919. One of seven children born to a poor family, he showed an inclination for music early in life. He was around eight years old when he heard an exponent of the Punjab gharana play tabla, and decided to pursue it, despite opposition from his family.

Having begun to play on his own, Alla Rakha left home at the age of 13 in search of an ustad — specifically, Mian Qadir Baksh of the Punjab Gharana, who lived in Lahore. It took him two years to earn his way to Lahore and into Mian Qadir’s tutelage, which he spent teaching the tabla and playing at music fairs. Mian Qadir himself came to see him after hearing of his exploits, and took him in as a student.

What followed was hours of rigorous practice or riyaaz. “Sometimes, I played non-stop for eight hours wearing a cotton vest and a lungi which used to get wet with perspiration,” Alla Rakha said in an interview.

After mastering the art, Alla Rakha became an artist for All India Radio in Lahore, later moving to AIR Delhi and then, within a year, to Bombay, now Mumbai.

His rapid rise brought him so much recognition that he began to be recognised as the greatest proponent of the Punjab Gharana of tabla, founded by Lala Bhawani Das, one of Emperor Akbar’s court musicians.

And yet, Alla Rakha liked to remain in the background — it is interesting to note in old videos available on YouTube that despite their partnership and virtually equal stature, he always sat a few feet behind Pandit Ravi Shankar rather than beside him. It was almost as if he shunned celebrity and believed in the accompanyist being understated.

Also read: Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, Hindustani classical doyen who wanted to spend his life in a garage

Mesmerising and shaping the West

Alla Rakha’s partnership with Ravi Shankar began in the 1960s when the two were selected to be part of a cultural delegation to represent India abroad. And so, while Europe and America were being taken over by ‘Flower Power’ and four smiling boys from Liverpool, the duo began shaping the beginnings of ‘fusion music’ by taking Indian classical music to the West.

The first big highlight of Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha’s sojourn was the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. But then came 1969, and the duo found themselves in the thick of things beside the guitar-burning Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock.

“On the same stage where Jimi Hendrix burnt his guitar and The Who trashed their instruments, (Ravi) Shankar sat cross-legged behind his sitar, calm and focussed, engaging in musical dialogues of thrilling virtuosity with his tabla player, Alla Rakha, in front of tens of thousands of stunned hippies,” an article in the New Yorker read.

Alla Rakha also recorded a studio album with an American jazz drummer Buddy Rich in 1968. Rich à la Rakha is “a battle royal between full drum kit and tabla”, said a review for the BBC. The album was considered a seminal work of East-West fusion music.

Alla Rakha also collaborated with and inspired many prominent rock artists of the 1960s and 70s. American percussionist and drummer of the rock band Grateful Dead, Mickey Hart, is a well-known admirer of the Ustad’s work.

“Ustad Allah Rakha is the Einstein, the Picasso; he is the highest form of rhythmic development on this planet,” Mickey Hart wrote last year.

Ustad Allah Rakha is the Einstein, the Picasso; he is the highest form of rhythmic development on this planet. He would have turned 99 years old today. Watch and learn more about this incredible man who shaped my life and the music of the @GratefulDead. https://t.co/yzO3FlFIRF

— Mickey Hart (@mickeyhart) April 29, 2018

Also read: Vijay Anand, the ‘guide’ to Dev Anand who was more than just a noir filmmaker

Abba ji

Today, son Zakir Hussain has far surpassed Alla Rakha’s fame, while another, Taufiq Qureshi, has diversified from Indian classical music to become a master of percussion instruments from around the world. But both credit their incredible success to the foundation their ‘Abba ji’ laid for them.

In an interview, Qureshi said Alla Rakha was a loving and lenient father who would never say no to his children, but when it came to teaching them, he was a completely different person — very particular about riyaaz, and one who made no exceptions.

Alla Rakha had a strict regimen for all his pupils — a couple of hours’ riyaaz before bed, an hour-and-a-half of riyaaz before school, and a couple of hours after returning home.

Zakir Hussain said he was always jealous of his father. “He could always produce this thick, fat, strong, round sound. I could never get the same fatness. So I had to improvise my own movements. What he’d do with one finger. I’d do with a full hand,” he said in an interview.

He had also said that for his father, music was like “intense religiosity”.

“There’s a rustic simplicity about him,” Hussain said. “A wisened innocence. He is always him and knows where he is going.”

But at 80 years of age, the curtain came down on this maestro’s life in tragic circumstances. Ustad Alla Rakha passed away after a heart attack on 3 February 2000, after hearing of his daughter Razia’s death from complications arising out of cataract surgery the day before.