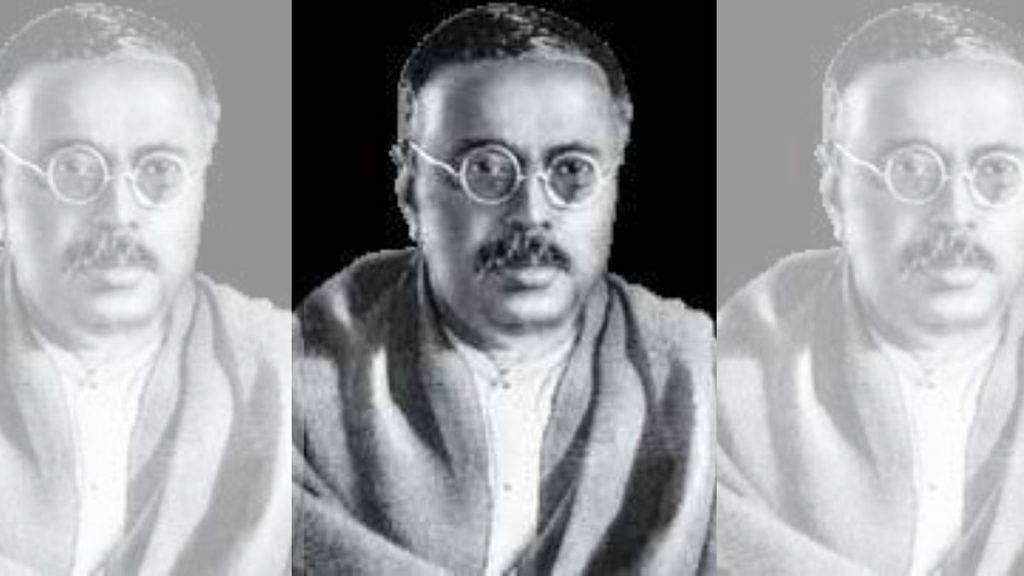

Any Indian interested in psychoanalysis would know about Sigmund Freud. But not many know about India’s first psychoanalyst Girindrasekhar Bose and that he and Freud even wrote to each other. In his first letter, Bose informed Freud about his unique ‘opposite wishes’ theory.

The theory deviated from Freud’s ideas. As explained by Professors Salman Akhtar and Pratyusha Tummala-Narra, according to ‘opposite wishes’, no wish exists without a counterpart in the psyche. A wish to hate is always accompanied by a wish to be hated and a wish to love by a wish to be loved. Individually, all wishes are pleasurable. Unpleasure arises only in conflict with its opposite. The mind resolves such conflicts by vacillating between the two wishes, usually by fulfilling one. The repressed wish, however, continues to exert its effect.

Akhtar and Tummala-Narra point out that Bose’s theory contained the seeds of ideas regarding projective identification and intersubjectivity long before these concepts were explicitly developed in the West.

First doctor of psychology

Born on 30 January 1887 in Darbhanga, Bihar, Bose was the youngest of nine children. His father, Chandrasekhar Bose was the Dewan of Darbhanga’s Maharaja Sir Rameshwar Singh’s estate.

Bose obtained his M.D. degree from a medical college in Kolkata in 1910 after graduating in science from Presidency College. When the University of Calcutta introduced graduate training in Psychology in 1916, Bose registered immediately. On completion, he joined the university’s Department of Psychology as a lecturer and would go on to head the department from 1928 to 1938. He completed his thesis titled The Concept of Repression in 1921, which became the first doctorate degree in Psychology conferred by an Indian University.

Although Bose had heard of Freud’s discoveries soon after he began his psychiatric practice, he had access only to newspapers and lay journal articles on Western psychoanalysis since English translations of Freud’s works were not available in India. Thus, according to Akhtar, Bose developed his psychoanalytic ideas almost independently of Freud by 1914. Despite a 30-year age gap, they wrote to each other for almost two decades between 1921-1937. The two never met each other.

Also read: Freud to Carl Rogers—psychologists have always focused on the past. But they might be wrong

Bose and Freud

In 1921, Bose first wrote to Freud seeking his opinion on his thesis The Concept of Repression, which had his theory of opposite wishes. Bose added that Freud had been a well-known name in his family for the past decade. The founder of psychoanalysis responded positively, praising the thesis for ‘correctness of its principal views and the good sense prevailing in it’.

Freud was greatly surprised that psychoanalysis, a fairly new field of study at the time and one that was hardly known outside the Western world, should have met with ‘so much interest and recognition’ in a far-off country.

The interaction had some fruitful consequences. The Indian Psychoanalytical Society was formed on 26 January 1922 at Bose’s residence in Kolkata barely three years after the British Psychoanalytic Society was formed.

Christiane Hartnack, the author of Psychoanalysis in Colonial India, points out that the ‘actual motor’ behind the formation of the Indian Psychoanalytical Society was Bose, and that the Society received affiliation in 1922 from the International Psychoanalytical Association even before the French one. Later in the same year, Freud requested Bose to join the editorial board for both the International Journal of Psychoanalysis and the German Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse as ‘leader and representative of the Indian group’.

Their correspondence was not always restricted to complex theories. Bose once requested Freud for his photograph. Before Freud’s response came in, Bose sent him another letter with a pencil sketch drawn by his friend and well-known artist Jatindra Kumar Sen. It was Freud’s image drawn ‘from imagination’. Bose added that the artist did not have the least idea about Freud’s features.

Freud replied, “the imaginative portrait you sent me is very nice indeed, far too nice for the subject.”

Ashis Nandy, psychologist, social theorist and author of The Savage Freud, asserts that Bose found in Freud a kindred soul and saw immense possibilities in psychoanalysis. With the aim of introducing the concepts of psychoanalysis to the Bengali reader, Bose published Swapna in 1928 on Freud’s concept of dreams and Manobidyar Paribhasha in 1953, a compendium of psychological concepts with explanations.

His own man

An intriguing aspect of Bose’s work is that though he was in direct correspondence with Freud and in contact with the Western academic world of psychoanalysis, his own interpretations were not mere reflections of it. He did not fully accept Freud’s ‘theory of libido’ and offered a different view based on his own theory of opposite wishes.

His understanding of psychoanalysis was enriched by his profound knowledge of Indian philosophy. As a teenager, he had been keenly interested in yoga and had also studied Patanjali’s Yogasutra. Several of his Bengali publications such as Puranapravesa,1935 and Pauraniki, posthumously published in 1956 were translations and interpretations of traditional Sanskrit texts. His article on the Gita published in 1931 in Probashi, a leading pre-Independence Bengali journal, has been called a pioneering attempt at correlating Hindu philosophy to Western psychology.

Freud acknowledged the unique perspective which Bose had brought to psychoanalysis— “The contradictions within our current psychoanalytic theory are many…and I reproach myself for not having given attention to your ideas before…I suspect that your theory of opposite wishes is practically unknown among us and has never been mentioned or discussed. This attitude was to be abolished. I am eager to see it weighed and considered by English and German analysts all over”.

Also read: Women’s Day awardee psychiatrist says media stokes mental health stigma, demonises disorders

A forgotten legacy

Though today Girindrasekhar Bose is largely a forgotten name outside specialist circles, it is important to remember the socio-cultural context of the time so that we may better appreciate his contributions.

In Ashis Nandy’s analysis, Bose entered the field of psychoanalysis at a time when social relationships, which took care of most of the everyday problems of the living, were breaking down in urban India. The first victims of this change were psychologically afflicted. Their families and the community were not willing to accord them space and care, rather they were viewed as ‘diseased and potentially dangerous waste products of society’. Bose chose to counter these perceptions and offered more compassionate treatment and care.

At his initiative, India’s first psychiatric outpatient clinic was established in Kolkata at Carmichael Medical College and Hospital (now RG Kar Medical College and Hospital) in 1933. On 5 February 1940, Bose opened a private nursing home and clinic in Ballygunge, Kolkata, which was managed by the Indian Psychoanalytical Society. Bose’s elder brother and well-known Bengali writer Rajsekhar, who wrote under the pseudonym Parashuram donated the house for the clinic and supplied furniture and medicines. Later renamed Lumbini Park Mental Hospital, it was the first mental health institution of its kind.

Bose also founded Bodhayana, a school for young children, including those with special needs, organised on psychoanalytic principles in 1949.

The Indian Psychoanalytical Society continues to function from Bose’s residence at 14, Parsibagan Lane in north Kolkata. The logo of the Society depicts Ardhanariswar (half male, half female) — a combined image of Shiva and Parvati symbolising the bisexuality of human beings.

Dr Krishnokoli Hazra teaches History at the Undergraduate level in Kolkata.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)