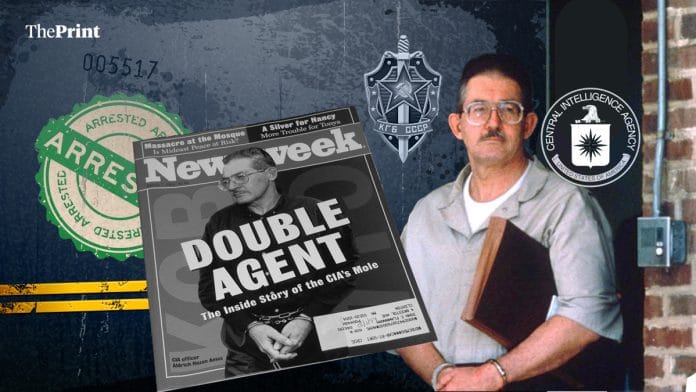

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) double agent Aldrich Hazen Ames remains one of Soviet Union’s and, later, Russia’s most successful penetrations into the American intelligence networks. Apart from the damage that he did to the US, there are some broader lessons to be learnt—in the world of espionage, there’s no nation nor intelligence officer who hasn’t been on the losing side of the double agent game.

New Delhi: Thirty-six years after he was arrested and convicted, the most successful double agent to ever penetrate and work inside the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) died this week at the Federal Correctional Institute at Cumberland, Maryland.

From 1985, when he first began selling secrets to the Soviet Union, Aldrich Hazen Ames compromised over 100 CIA operations. He enabled the execution of at least 10 high-level sources and helped plant disinformation which made its way to three United States presidents.

An official investigation concluded that he caused “more damage to the national security of the United States than any spy in the history of the CIA”.

For the most part, the spies and double agents of the Cold War—like MI6 officer Kim Philby, or nuclear spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg—betrayed their nations on ideological principle. Ames betrayed America for a Jaguar XJ6 sports car, designer suits, a $500,000 home, and household help hired from the Philippines whom he paid to travel over.

Hi, and welcome to this episode of ThePrint Explorer. I’ll be looking at the most important lesson of the Ames case, which is how easy it was for him to get away with it. Why? Like all bureaucracies, intelligence services—even the best ones—tend to get mired in process and procedure. And in the shadow world of espionage, it’s only too easy for them to lose touch with common sense. The cost of mistakes, as the CIA would discover, has to be paid in blood.

Who was Polyakov? A double agent just like Ames, but the other way around—working for the Soviet external intelligence service, but really working for the CIA. Sandra Grimes, who unmasked Aldrich Ames, and was one of the CIA’s most brilliant Soviet Union experts, said: “Polyakov was a crown jewel, the best source, at least to my knowledge, that American intelligence has ever had.”

Polyakov was sold to the Soviet Union together with many other American agents for cash down.

Also Read: British, Soviets & Americans returned from Afghanistan. Pakistan, Munir need to learn from past

Parallel lives

Late one afternoon in the spring of 1988, English teacher Nina Polyakov—Polyakov’s wife—arrived home to find a letter stuffed inside the mailbox of her Moscow apartment. There was no stamp on the envelope. Inside was an official form.

“We inform you that Dmitri Fyodorovich Polyakov died on March 15, 1988,” it read. The space meant to record the cause of death had been left blank.

Today, we know Polyakov was likely shot through the back of the head in Lefortovo prison. The place he was buried has never been revealed to his family or anyone else. The story of a traitor to the Soviet Union almost always ended in an unmarked grave.

Dmitri Polyakov wasn’t just a Soviet general—he was America’s greatest Cold War spy.

For 25 years, he fed the CIA secrets that shaped history, until two American traitors sealed his fate.

This is the story of the man who betrayed the Soviet Union to save it: pic.twitter.com/Ds6YvErQtS

— History Nerd (@_HistoryNerd) December 25, 2024

A decorated hero of the Second World War, Major General Polyakov joined the Soviet foreign intelligence service, the GRU, after that conflict. From 1951, he ran highly successful espionage ring in New York operating under diplomatic cover from the Soviet UN mission.

Later, Polyakov became disgusted with the corruption of the Soviet elite. he was angered in particularl the shabby treatment given to Marshal Georgy Zhukov, widely acknowledged to have been one of the great commanders of the Second World War, by the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin.

Although Zhukov was rehabilitated by Stalin successor Nikita Khrushchev, Polyakov had nothing but contempt for this leader too. To Polyakov, it appeared Khurschev was personally crude, and politically inept.

In 1961, increasingly upset about the direction the Soviet Union was heading in, Polyakov approached American diplomats in New York seeking a meeting with the CIA. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which had long been watching Polyakov, handled the case instead.

There is a little doubt Polyakov acted out of ideological disillusionment. He accepted only $3,000 a year and even refused resettlement in the US.

At around the same time, Aldrich Ames was beginning his adult life. The son of Carlton Seal Ames and Rachel Ames, Aldrich Ames was born at Riverfalls, Wisconsin in May 1941. That’s about the time Polyakov had joined artillery school in preparation for his tour of duty on the Eastern Front.

The elder Ames who held a PhD degree from the University of Wisconsin joined the CIA in 1952. His career, however, didn’t prove very illustrious. The senior Ames served only one foreign tour from 1953 to 1955 and received a negative appraisal because of his alcohol dependence. He was, however, allowed to continue serving in the CIA and finally retired in 1967.

Aldrich Ames, meanwhile, joined university in 1959, working part-time at the CIA to help fund his studies. His passion for lit theater, though, meant he did not devote adequate time to his studies and failed his first-year college examinations.

In 1962, though, he was given a clerical job at the CIA, even though he admitted he’d had a couple of small brushes with the law back in college, involving what else? Alcohol-fueled rowdiness. From the outside though, it appeared that the young Ames was determined to get his life together.

In 1967, after he got his CIA job, he graduated from George Washington University with a respectable, if not spectacular, B minus grade in history. He joined an officer training programme and then married a colleague in 1969. The alcohol continued. There were minor brushes involving alcohol-related behaviour in 1962, 1963 and 1965. But, the CIA chose to overlook this behaviour.

Ames was posted to Ankara together with his wife in 1969. But his performance was graded well in 1967, though it fell off in subsequent years overseas. He was posted back to Washington in 1972 and then trained as a Russian language expert. For the next nine years, he worked on operations targeting Soviet nationals in the US, now receiving good reviews from his superiors.

The problems with alcohol continued, but it’s worth remembering he’d never received an official reprimand throughout his entire career. Perhaps, those were just more clubby, forgiving years for this kind of thing.

So then in 1981, he received a foreign posting again, this time to Mexico City. There he met the much-younger Mara del Rosario Casas Dupuy, the cultural attaché at the Colombian embassy and a paid CIA source. He neglected to tell his bosses about this new romantic relationship, and also neglected to tell Rosario that he was already married.

The CIA officer’s divorce finally came through in 1985, and Rosario moved back to the United States, and there a new bunch of problems began.

In 1983, Ames was posted back to Washington as head of the counter intelligence branch. He started working towards getting divorce, and around that time he first encountered the name of America’s top Soviet double agent.

Polyakov’s turning

Late in 1962, posted back to Moscow, Polyakov had given his first gifts to the US, a list of four American military personnel working for the GRU, as well as as its more famous domestic counterpart, the KGB.

These four were Jack Dunlap, an army sergeant assigned to the National Security Agency, who was copying top secret codes and then selling them; Lt. Col. William Whalen, a Pentagon staff officer who was sharing information on atomic weapons and missile strategy; Nelson Drummond, a Navy clerk with high-level clearances who was providing information on weapon systems, electronics, training and operating manuals; and Herbert W. Boeckenhaupt, an Air Force sergeant who was selling detailed cryptographic and other secret communication information.

As a bonus, Frank Bossard, a technical officer in the British Ministry of Aviation, was also revealed by Polyakov to be a spy.

Although he did not know it, Polyakov had arrived in the center of a growing crisis within the CIA itself.

In 1963, the British Secret Intelligence Service MI6 officer Harold Philby, Kim Philby as he’s widely known, had defected to the Soviet Union after being exposed as a spy. First recruited when he was a young communist back in college, Philby had handed over the most treasured secrets of Western intelligence to the KGB and the GRU.

Among other things, Philby had sent dozens of CIA agents to their death. CIA agents who’d been parachuted secretly into the Soviet Union and then disappeared. Among the most shaken up by this defection was the CIA’s counterintelligence chief, James Jesus Angleton.

Angleton had shared the details of all those parachutists with Philby, who he considered to be not just a mentor, but a close personal friend. Angleton responded to the deep blow by retreating into a paranoid world where everyone, including his colleagues, were suspects.

The mid-ranking KGB officer Anatoliy Golitsyn who had defected in 1961 took full advantage of this. Golitsyn claimed there was a Soviet conspiracy underway to penetrate the US using four defectors and provocators. Everyone who came to the US after him, Golitsyn essentially said, would be a KGB spy. A proposition that perfectly matched Angleton’s growing mania.

Even though the FBI officers who watched Polyakov for five years in New York rejected all notions that he was a plant, Angleton persisted in his witch hunt for moles and plants, creating chaos and ill-will within the CIA. The witch hunt persisted even after an in-house CIA psychological assessment concluded that Golitsyn was a fantasist, who demonstrated some signs of mental illness.

Among the victims of Angleton’s mania was another KGB defector, Yuri Nosenko, who confirmed that the assassination of President John F. Kennedy was not a Soviet agent and that it wasn’t a Soviet plot. In return, Angleton imprisoned Nosenko illegally for three years under extraordinarily harsh conditions. The bare light in Nosenko’s cell was never turned off. He had no blanket or pillow. He was given nothing to read and no writing material.

Even though Angleton had no influence over the Polyakov operation, he waged a battle of attrition against the information that the major general was offering. Among other things, Angleton insisted that Polyakov’s information on the emerging Sino-Soviet split was a carefully crafted fiction. All this talk of the Chinese and the Soviets falling apart, Angle Angleton said, was just being fed to deceive and confuse the Americans.

To add to the paranoia and tension, Finnish-American Kaarlo Tuomi, a man Polyakov had trained and recruited in New York, was publicly identified as a double agent in the course of an espionage trial. The media coverage of the incident also identified Polyakov as a spy.

Now, this was potentially career destroying publicity. Not only was one of Polyakov’s star spies revealed to have actually been working for the CIA, Polyakov’s name itself was up in print for the whole world to see.

And on top of it all, CIA officers in Moscow were showing outright incompetence. On one occasion, they failed to realise that Polyakov had left a microfilm with vital information in their agreed secret dropbox.

Polyakov was utterly appalled by this just complete incompetence and severed all contact for several weeks. Then came a break. In 1965, Polyakov was transferred to the Asia division of the GRU and sent to Yangon, Rangoon as it was then known. The next summer, he resumed direct contact with the CIA, passing on detailed assessments of events in Vietnam and China.

The relationship was again severed in early 1971, six months or so after Polyakov was posted back in Moscow. Polyakov did so because he was convinced with good reason that the CIA simply lacked the discipline and skills to maintain a covert relationship in Moscow where the gaze of the KGB on everything that was going on was deeply intense.

Glory years in Delhi

Late in 1973, Polyakov was posted to New Delhi. His CIA handler, Paul Dillon, followed a few weeks later, moving into a house in South Extension 2 together with his family. This time was to prove exceptionally good for Polyakov. He was promoted to major general and received a second Order of the Red Star.

The period was also exceptionally good for the CIA. Polyakov succeeded in persuading his GRU bosses that Dillon was a potential source, which meant the two of them could have easy and frequent contact.

Among other things, Polyakov gave Dillon critical evidence that Soviet generals had come to the conclusion that a future nuclear war would be unwinnable. This was information that would directly influence American decision-making through the remaining years of the Cold War. It was completely stunning news because it meant the Soviet Union had no intention of using its nuclear weapons.

Polyakov returned to Moscow from Delhi in the fall of 1976 and was assigned as chief of the third faculty in the GRU’s military diplomatic academy. That was the unit that trained intelligence operatives from both the USSR and its allied Soviet bloc countries. Now, this gave him direct access to the names of all military intelligence agents preparing to go overseas.

This time, the CIA had actually prepared a little better for the challenges of maintaining contact with Polyakov without being detected by the KGB.

The general had been given a very special special transmitter that sent 2.6 second long bursts of information to a receiver inside the US embassy in Moscow. Even though KGB radio communication specialists knew that information was being broadcast in the area of the embassy, they had no way back then of deciphering this material or locating its origin. The burst messages were just too short.

Early in 1979 though, the first blow fell on Polyakov’s operation. An FBI officer named Robert Hanssen walked into the Broadway office of Amtorg, the Soviet trading mission known to front for the GRU, and volunteered information that Polyakov was spying for the US. A computer operator in the FBI, Hanssen had access to the FBI’s list of America’s Soviet intelligence assets.

Now, an internal investigation proved inconclusive, but the GRU retired Polyakov just in case what Hanssen was telling them was correct.

The downfall

Following divorce, Ames and his wife, meanwhile, signed off on financial arrangements committing him to pay $300 a month for the next 42 months. To this debt, which would amount to a little more than $125,000, Ames also agreed to pay outstanding credit card and miscellaneous debts, which were some $33,350.

Now, if that sounds like very little money, remember this was 1985 and Ames believed this would completely bankrupt him.

He hit on a simple and deadly solution. Early in 1985, he met one of several Soviet diplomats he had already been dealing with using an assumed name and job description. He offered the KGB the names of at least three double agents for $50,000 in cash. Later that summer, he handed over encrypted communications traffic, identifying 10 more agents.

Late in 1985, the CIA’s assets in Moscow began disappearing one after another, just as they had after Kim Philby’s treason. “They were wrapping up our cases with reckless abandon,” a CIA officer later told an official investigation.

Vitaly Yurchenko, a Soviet defector to the CIA, identified this traitor as an individual codenamed Robert.

Following a process of elimination, the CIA’s counterintelligence division identified Robert as Edward Lee Howard, an officer working in the Soviet division. The discovery of Howard though did not fully address the problem.

Through the rest of 1985, the CIA Soviet spies continued to disappear. Those assets whose arrests were reported in the fall of 1985 was regarded among the most important CIA human sources at that time. Investigation by the US Senate found: “All of those sources were later executed.”

Now, Howard, the CIA knew, was aware of only half the agents the KGB had found. And more important, arrest continued after he was put into jail. CIA chief William Casey ordered a fuller investigation in early 1986.

But this is where James Jesus Angleton, remember the guy who’d gone crazy with his witch hunt, where his shadow cast a malevolent darkness over proceedings.

Angleton’s unfounded allegations earlier had ended up destroying lives and careers. Following Howard’s escape to the Soviet Union through Finland, official investigations had called on the CIA to plug holes in its counter intelligence system. And in the process of doing so, no one in the CIA wanted to face allegations like those which emerged from Angleton. No one wanted to be the guy who wrongly ruined somebody’s life.

The Soviet division, meanwhile, got a little cheered up because it was finding new sources. To the CIA leadership, it seemed like the damage had been controlled.

Aleksandr Zhomov, a KGB officer assigned to watch the US embassy in Moscow and its C CIA contingent, approached the CIA station chief in 1987 and offered to sell inside information in exchange for payment and subsequent reach settlement.

Zhomov said he could obtain documents explaining how his service had managed to unmask and arrest virtually all of the CIA Soviet agents in 1985-1986. This was almost too good to be true. Actually, it was too good to be true. Like other new agents who showed up in this period, Zhomov was later revealed to have been operating as an agent for the KGB.

The new crop of recruits and agents who joined in 1986 retired peacefully the Soviet Union, which of course established their real identities but much later. These KGB plants told the CIA that its agents had not been compromised by a double agent at all. It they were actually done in by their own poor trade craft and personal shortcomings.

Low-level Soviet agents like embassy security officer Clayton Lowtree were investigated for letting information leak to the KGB.

The sheer scale of the problem though kept bothering CIA counter intelligence. There was much too much evidence that there had been a traitor in 85-86 and an exceedingly well-informed traitor at that.

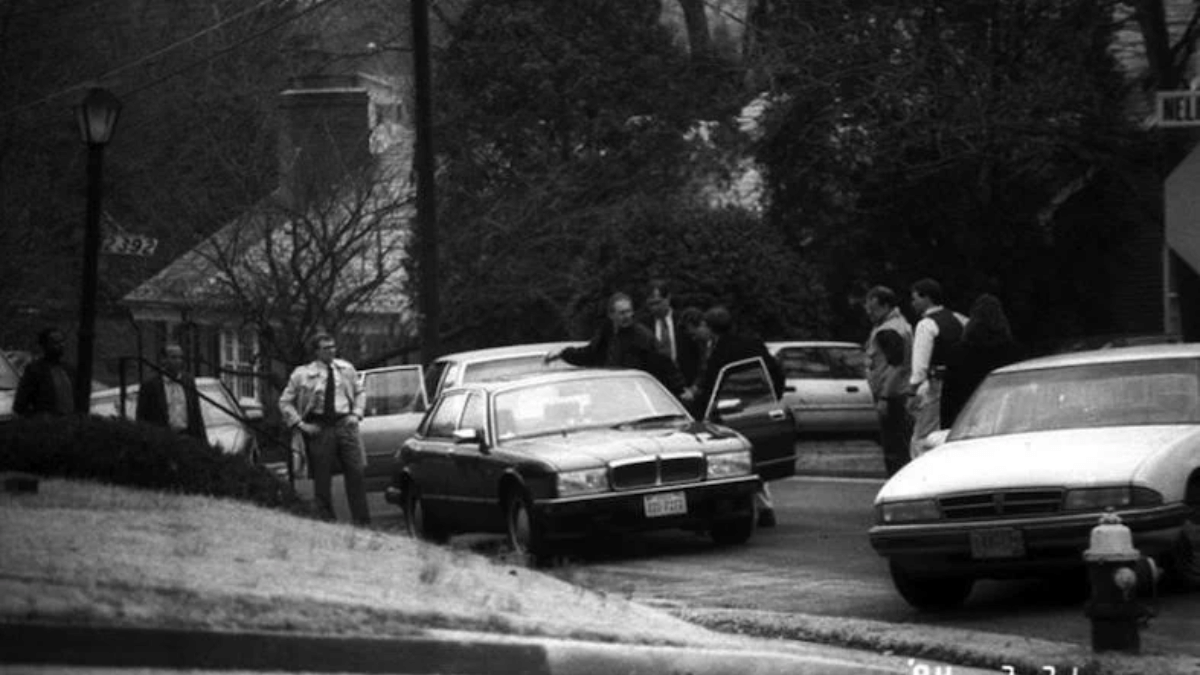

The FBI was brought in and joined the hunt. Evidence gathered by the FBI showed that Ames, who they went back to investigate, spent $1,397,000 between 1985 and 1993.

In addition to this fancy Jaguar and fancy house in DC, Ames had bought condominiums as well as a farm at Bogota and Cartagena in Colombia, his wife’s home country. He also paid for his wife’s education at Georgetown University. Now, Ames’s salary for this entire period was cumulatively $336,000. He spent more than four times that amount.

The unusual and obvious affluence of the Ames had led the FBI to focus on them. But this had drawn the attention of colleagues before. Ames responded by giving the impression that the money came from Rosario’s family in Colombia—an untrue story that the CIA failed to ever really check.

When the evidence finally mounted up, Ames signed a plea agreement in 1994. Basically, he accepted spending his life in prison if Rosario was allowed to leave for Colombia with their son.

Ames admitted in court to having compromised, “virtually all Soviet agents of the CIA and other American and foreign services..”

His pre-agreement stated, “For those persons in the former Soviet Union and elsewhere who may have suffered from my actions, I have the deepest sympathy, even empathy. We made similar choices and suffered similar consequences.”

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan had requested President Mikhail Gorbachev to pardon Polykov. That request came just a little bit too late. It turned out he’d been executed a few days earlier.

Lessons

There’s no nation nor intelligence officer who hasn’t been on the losing side of the double agent game. Former CIA director Richard Helms once told Congress that detecting a double agent operation is, “one of the most difficult and tricky aspects of intelligence work. And there isn’t anybody who’s been in it for very long, who hasn’t been tricked once, twice, maybe many times”.

Another former CIA director, William Casey, even gave one double agent a gold medal and a $10,000 bonus for his services.

In 1987, when Cuban intelligence officer Florentino Aspillaga Lombard defected to the CIA, he revealed that almost all of the CIA’s Cuban agents, some four dozen over a 40 year period, were actually double agents working for Havana.

This was hushed over at the time, but now historians have been able to establish this was a completely accurate claim.

And former East German intelligence chief Markus Wolf said that, I quote, “By the late 1980s, we were in the enviable position of knowing that not a single CIA agent had worked in East Germany without having been turned into a double agent or working for us from the very start.” Former CIA Director Robert Gates later admitted the CIA had indeed been duped.

Does this mean that the CIA was exceptionally stupid? No. It had great successes of its own on top of all this bad luck, which we’ll have to tell the story of perhaps in another episode.

The solution, though, was to ensure constant accountability to ensure spy chiefs and organisations were compelled to constantly enhance their defenses and always stay alert.

The Ames case was followed by exhaustive investigations by the CIA’s own inspector general as well as the Senate Intelligence Committee, all of which are now public. Those investigations brought about wide-ranging improvements in CIA operating procedures.

An even more important lesson though is that spies and spycraft, perhaps, really don’t matter that much to the grand strategic balance of power.

Ames after all like Philby before him did not even marginally dent the economic and technical supremacy of the US. Even as Polyakov was executed, the Soviet Union was the on the edge of a precipice into which it would fall.

This then is the ultimate irony. The spy games, which claimed so many lives, perhaps, amounted to piteously little.

(Edited by Tony Rai)