New Delhi: It was unchecked mining that began the debate to define the 2-billion-year-old Aravallis in India 15 years ago. Now, the legal debate appears settled by the country’s highest court. But not without generating renewed interest in preserving the ranges older than the Himalayas. It’s an open pit witnessing the fight between development and conservation, from which may emerge a new green charter for India and its forests.

Last month, the Supreme Court ruled that only hills measuring 100 metres or above in height would qualify as part of the 650-km-long Aravalli ranges in northwest India. It’s the same definition that the Rajasthan government had been using for 20 years, but there isn’t necessarily consensus on this criterion. For a highly eroded mountain range characterised by undulating ridges rather than towering peaks, this definition is effectively a death knell, according to environmentalists and protesting groups such as Aravalli Bachao. The SC’s own Amicus Curiae cautioned that it would open up the lower hills to incessant mining.

“What is even the need of ‘defining’ the Aravallis? Have you ever defined the Shivaliks, the Vindhyas, or the Himalayas?” asked MD Sinha, a former Indian Forest Service officer posted in Haryana. “Everyone knows what the Aravallis are; they’re self-evident.”

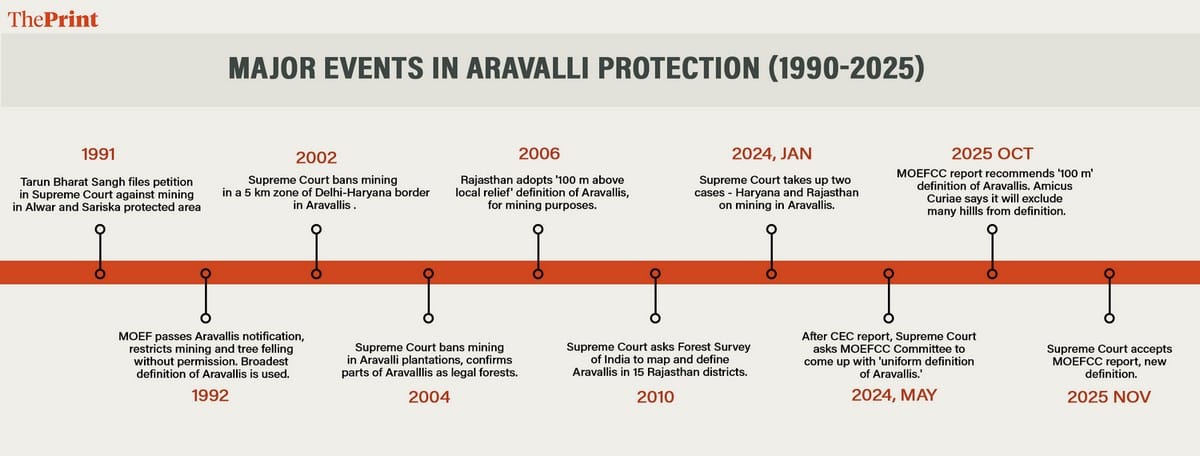

The quest to define the Aravallis, though, has been a long time in the making, with prolonged court battles and public protests along the way.

From the 1980s, as India’s early ecological conservation framework took shape amid the mining rush in the mineral-rich Aravallis of Rajasthan and Haryana, through the real estate boom and encroachment of the early 2000s, the range’s modern history runs parallel to the story of environmental protection in India.

Geologically, the Aravallis predate the Himalayas by hundreds of millions of years. In independent India, institutions such as the Supreme Court and the National Green Tribunal have been the champions of regulating mining and construction in the region, cheered on by citizen activists and environmentalists.

The new order, however, may set a new course for India’s environmental planners.

“I’ve seen the Aravallis in Haryana sliced and butchered like salami in front of my eyes, and felt the environmental consequences of this concretisation,” said Vaishali Rana, an environmental activist and trustee of the Aravalli Bachao movement. “We don’t exaggerate when we say ‘no Aravallis, no life’.”

Also Read: SC ruling on sustainable mining in Aravallis: What continues, what stops & what comes next

How the new definition came about

After a year-and-a-half-long case, on 20 November, the Supreme Court adopted a first-of-its-kind “uniform” definition of the Aravallis across Gujarat, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Delhi.

Aravalli hills will now be classified as such only if they are 100 metres or more in height across any of the 37 Aravalli districts. An Aravalli range, meanwhile, will consist of two or more such hills located within 500 metres of each other.

“After this new definition, more than 90 per cent of the area under the Aravallis is now protected,” said Union Minister for Environment, Forests and Climate Change Bhupendra Yadav at a press conference on Sunday.

The new definition was accepted after the Supreme Court began hearing two separate cases in early 2024 related to mining in the Aravallis—one in Haryana and the other in Rajasthan. Both cases examined the environmental impact of sand, stone, marble, and other mining activities in the Aravallis despite repeated court orders prohibiting them.

“This court … also noticed that one of the major issues with regard to the illegal mining was on account of different definitions of Aravali Hills/Ranges as adopted by the different States,” said the SC’s judgement on 20 November.

Following this observation in May 2024, the Supreme Court ordered consultations with the Central Empowered Committee, secretaries of all Aravalli states, and an MOEFCC-powered committee, leading to the definition it ultimately adopted in November 2025.

In Rajasthan, hill-height–based definitions have earlier been used to determine whether mining bans apply to parts of the Aravallis. That history has triggered concerns among activists that the new parameters could weaken protections by making more areas eligible for mining, despite reassurances to the contrary from the government.

Boom, then bans—tension over mining

Government documents describe the Aravallis as the “green lungs of India”, yet their mineral wealth has also helped build the country. These two features are the crux of the development vs ecology conflict over mining.

Continuous hills cutting across four northwestern states, the Aravallis play an important role in maintaining the region’s tree cover and water table. They also act as natural barriers against the spread of the Thar Desert, protecting cities such as Alwar, Jaipur, Delhi, and Gurugram from desertification.

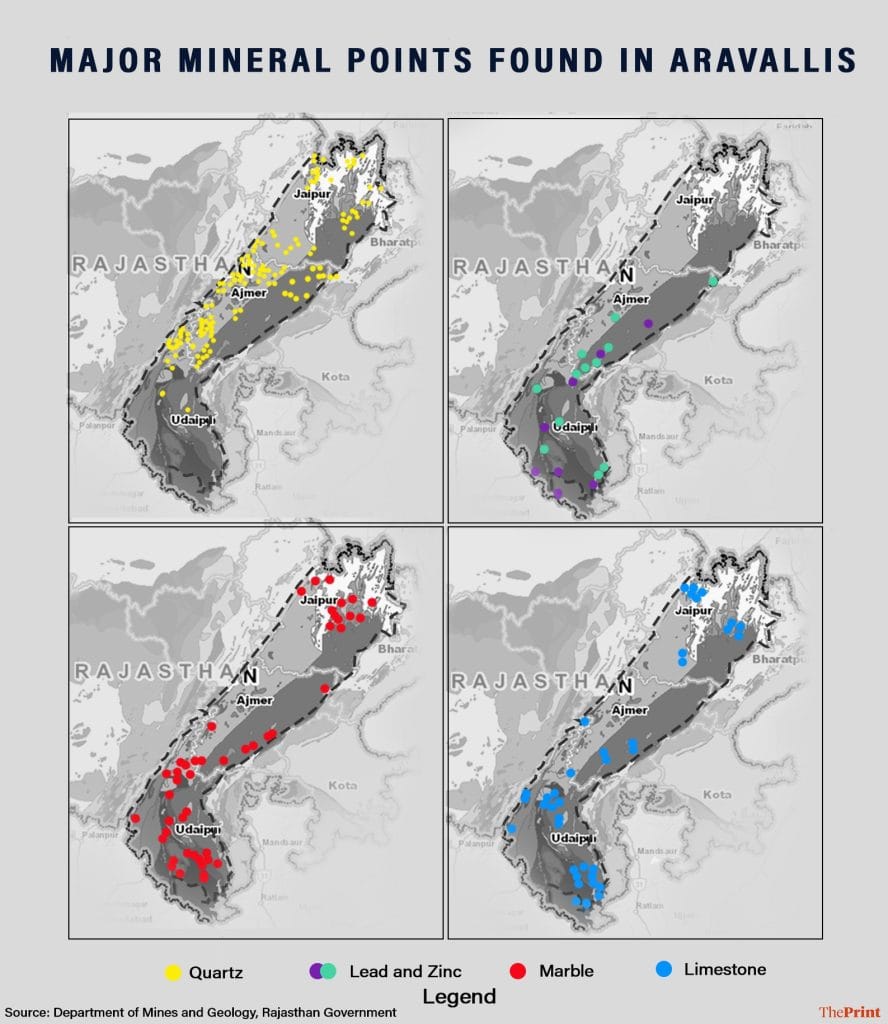

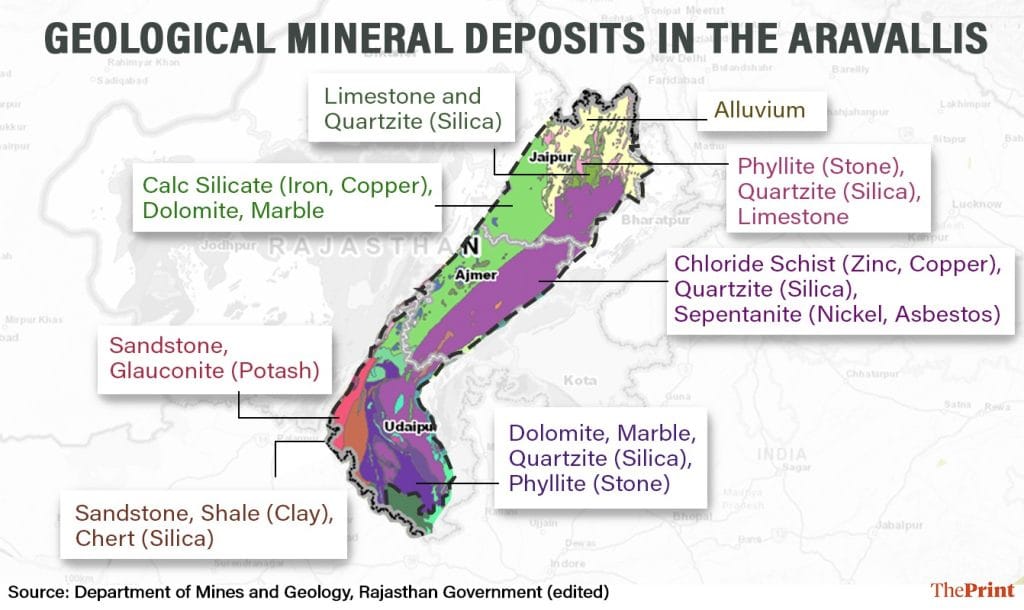

At the same time, the Aravallis have served as building blocks for the country for centuries. The hills are abundant in zinc, copper, lead, quartz, and stones such as limestone, marble, and granite.

Part of the reason the Aravallis are so endowed with mineral deposits is their age. Geologically, the Aravallis date back to a time when the Earth was still undergoing major changes to become what it is now. The Indian subcontinent as we know it did not exist, and the Indian plate was part of the Gondwana landmass. Formed during the Proterozoic era, roughly 1.8-2 billion years ago, the Aravallis are known as ‘fold mountains’ since they were created when tectonic activity led to plates folding together. For context, the oldest dinosaur fossil is only about 245 million years old, and ancient humans only showed up in one million years ago.

Evidence of mining in the range dates back to the 14th century, when areas in present-day Udaipur were mined for zinc and copper.

“The Taj Mahal is entirely built using marble from the Aravallis,” said MD Sinha. “Aravalli minerals have been used to build the country, in fact.”

That tradition continues. Rajasthan mines Aravalli hills near Alwar, Bhilwara, and Rajsamand for major minerals. Even now, more than 80 per cent of Rajasthan’s total mineral revenue comes from zinc and limestone mining. In Haryana, meanwhile, mining takes place in districts such as Faridabad, Nuh, and Gurugram.

Restrictions, however, entered the picture in the 1980s, as India enacted its first, broad-based Forest Conservation Act. Issues of deforestation, soil erosion, and the impact of unsustainable mining on human health entered national conversations.

“In the 1980s in the Aravallis, there would be 10 trucks loaded with silica being mined every day,” recalled Sinha. “They would pump out the water from the lower hills and get 5-6 feet of dry silica. It drastically reduced the water table in both Rajasthan and Faridabad.”

One of the first major legal challenges related to the Aravallis came from Alwar-based NGO Tarun Bharat Sangh in 1990. The organisation approached the Supreme Court over unsafe limestone mining and falling groundwater levels, particularly around Sariska National Park. The court ruled in the NGO’s favour, setting a precedent for prioritising environmental protection over mining in ecologically sensitive areas.

A year later, the Union Ministry of Environment (MOEF, as it was known then) passed the landmark 1992 Aravalli Notification. Merely two pages long, the document provided the broadest protection for the Aravallis by restraining “activities causing environmental degradation.” Mining, industrial expansion, tree cutting, construction, and even laying electrical lines were restricted without permission from the Union government. This protection, however, applied only to the Aravallis in Alwar and Gurgaon districts, where mining activity was most evident.

Significantly, 1992 was also the first and only time the Union government formally “defined” the Aravallis. But instead of using elevation or physical terrain, the definition relied on land-use categories recorded in revenue records. Areas marked as ‘gair-mumkin pahad’ (uncultivable hill land), ‘banjan beed’ (uncultivated or common land), ‘rundh’ (forested or protected land), and related categories were treated as part of the Aravallis.

Back then, these terms were sufficient for state governments, courts, and local officials.

“You go to any tehsil office or revenue office even today and ask them what the Aravallis are, they will tell you these exact words. Even people living near Aravallis know exactly what and where they are,” said Vaishali Rana. “When there is no local confusion, why did the need to define them even arise?”

Growing cities and grassroots protests

Parallel to the mining boom in Rajasthan was the real estate boom in Haryana, especially Gurugram. Older residents and forest officials recall how acres of lush Aravalli forest, little by little, gave way to construction companies and the concrete jungle of Gurugram.

In the nascent years of development, the 1990s saw clashes between the real estate industry and environmental regulators, with cases such as Ansal Properties vs Haryana SPCB in the High Court. While the Haryana Pollution Control Board argued that farmhouses built by Ansal in Raisina, Gurugram, stood on Aravalli land, the court finally ruled that the land was classified as ‘farm land’ in revenue records, and the argument did not stand.

But a new front opened up in years to come. With the steady concretisation of Gurgaon (now Gurugram) came a new army of citizen activists and environmentalist groups fighting against Aravalli destruction. A forerunner was the Aravalli Bachao Citizens’ Movement. Over the last 15 years, its trustee Rana has filed PILs, approached forest officials, and staged protests against illegal, non-forestry activities in the Aravallis around Gurugram and elsewhere in Haryana.

“It began when I moved to Gurgaon around 2010 and realised the area I lived in, Gwal Pahari, was a no-go construction zone because it used to be part of the Aravallis,” said Rana. “Slowly, I became aware of how much of where I live and what I see around me was part of an ancient, critical mountain range that was decimated by mining and construction.”

As avenues for legal resistance expanded with the establishment of the National Green Tribunal in 2010, cases related to Aravalli protection were registered there as well. In 2013, activist Sonya Ghosh approached the NGT with a petition to stop illegal construction by diverting ‘gair mumkin pahad’ land in Haryana.

From protesting illegal commercial establishments to filing PILs against unregulated blast mining, other citizen groups like People for Aravallis have led a bottom-up movement to protect the Aravallis over the past two decades.

“Most of the activism and concern for Aravallis in the last 20 years has come from citizens,” said former forest officer Sinha. “They’ve taken on the role of vigilantes, petitioners, and doggedly followed up with courts to enforce mining bans.”

Why was a definition needed?

For years before and after the 1992 notification, the Aravallis were protected by courts and governments with no real need to define them. As cases of mining, deforestation, and construction began cropping up, the Supreme Court passed successive orders restricting or banning these activities in specific areas, but did so without relying on formal definitions.

In 1996, 2004, and 2008, SC judgments under the MC Mehta vs Union of India case sought to preserve parts of the Aravallis and their green belt against deforestation and mining. In these hearings, what constituted the Aravallis was treated as self-explanatory and was not a point of contention.

MD Sinha argued that the question of definition was pushed later by mining lobbies.

“After about a decade of court orders banning mining in the Aravallis, the issue suddenly became about ‘what are the Aravallis?’,” said Sinha. “The court noticed how in many places mining and quarrying were continuing, with the justification that the area doesn’t officially fall under the Aravallis.”

Forest policy analyst Chetan Agrawal also said that it was only in 2010 that the Supreme Court decided to take up the question of defining the Aravallis. It, however, did not accept the Rajasthan definition back then.

In 2006, the Rajasthan government had adopted a definition based on geologist Richard Murphy’s classification, using a 100 m height benchmark to determine whether a hill qualified as part of the Aravallis or not. In areas that did not meet the benchmark, the Aravalli mining restrictions did not apply.

“But the Supreme Court in 2010 pulled them up on it, and said that this was Rajasthan’s ‘deemed’ definition of the Aravallis,” said Agrawal. “They instead instructed the Forest Survey of India to conduct ground truthing exercises and define the Aravallis accordingly.”

This 2010 Forest Survey of India (FSI) report demarcated the Aravallis in Rajasthan’s 15 districts as covering around 40,481 sq km. According to a report in the Indian Express, the FSI also mapped 12,081 hills as belonging to the Aravallis in these districts, out of which only 1048 (8.7 per cent) were over 100 m in height. The FSI also proposed a definition based on terrain rather than height, identifying Aravallis as hills with gentle slopes, a 100 m foothill buffer, and a distance of 500 m between hill formations.

In 2025, the court faced the same choice it had in 2010: a 100 m height parameter — this time backed by the MOEFCC committee — or the Forest Survey of India’s 2010 terrain-based definition.

Amicus Curiae K Parameshwar had a clear preference that “there should have been no reason for the Committee to not accept the definition as proposed by the FSI”.

The 20 November judgment, however, took into account ASG Aishwarya Bhati’s presentation that the FSI definition would “exclude” large portions from the Aravallis. There was no further explanation provided on how this would happen, and no data on how the Committee’s ‘100 m’ definition would include more area.

Also Read: Rajasthan: Over 27,000 illegal mining-related cases in Aravallis since 2020, but FIRs for only 11%

What now?

The main concern raised by citizens, experts, and even the Amicus Curiae in court is what the new definition includes, and what it leaves out. To date, the Government of India has not conducted a comprehensive survey of the Aravallis to verify how much area the range covers, how many hills there are, or how many rise above 100 m in height.

“We have the FSI survey in Rajasthan, which clearly tells us less than 1 per cent of the hills surveyed were above 100 m in height,” said Agrawal. “That is government data, telling us that 100 m is an arbitrary definition for Aravallis because the majority of the hills are not that high.”

The MOEFCC committee report did not spell out why the 100 m cutoff was chosen. Nor does any official data show how many Aravalli hills actually fulfill that criteria, leaving the FSI survey as the only available reference point.

“That survey is clearly not in favour of setting 100 m as the benchmark,” said Sinha. “Now more than 90 per cent of the Aravallis would no longer count as Aravallis.”

Rana and Sinha both said the government must explain the logic behind the definition and demonstrate how it aligns with claims that most of the Aravallis will indeed be protected under it.

“The best mining is done in the foothills, because that’s where the richest deposits are,” said Sinha. “If you only protect the tall peaks as Aravallis, you’re effectively opening up the foothills to mining.”

Rana also questioned how the new definition would affect decades-old protections, such as the 1992 notification for Alwar and Gurugram districts.

“In 1992, the government had said that all gair mumkin pahad would be protected as Aravallis. Is that null and void now?” she asked.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)