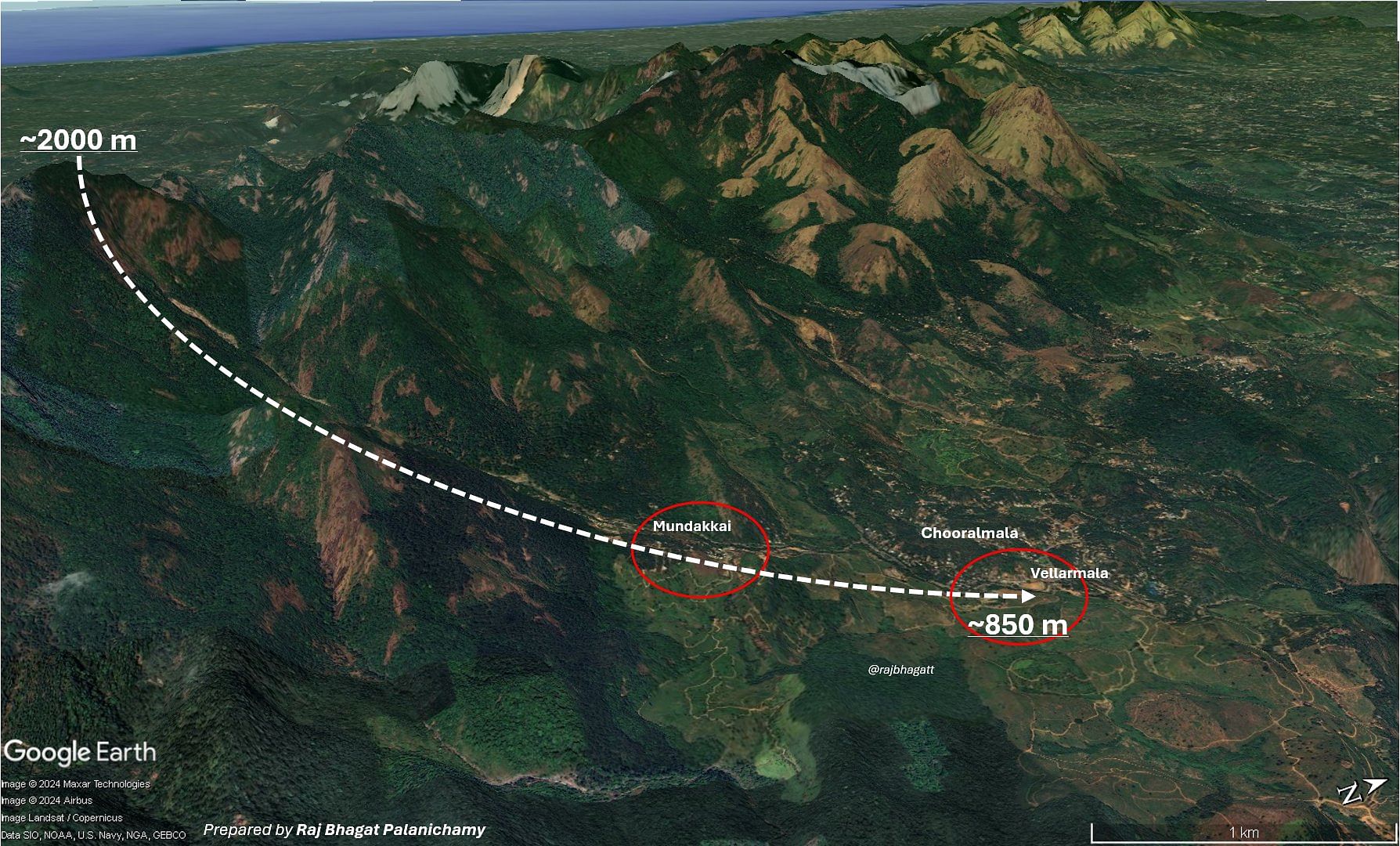

New Delhi: Iruvazhinji, a tributary of Kerala’s fourth longest river, reaches an altitude of 2000 metres, before plunging to 971 metres at Mundakkai in Wayanad district. Come monsoon, this steep slope lends to it the force and velocity that turned Mundakkai into ground zero of the catastrophic landslides that buried whole villages in the dark of the night, and have so far claimed 174 lives with another 170 people unaccounted for.

Kerala is home to four of the ten top landslide-prone districts in the country, according to ISRO’s Landslide Atlas (2023).

Wayanad is 13th on the list, behind Thrissur, Palakkad, Malappuram and Kozhikode.

On 30 July, the district received over 14 cm of rainfall in a single day, 493 percent more than the normal (2.39 cm). Triggered by this heavy rain, a series of landslides struck Chooralmala, Mundakkai, and Vellarimala villages in Wayanad early Tuesday.

This was not the first time a deluge of mud and water swept away whole settlements in Wayanad. During the devastating floods in 2018, Wayanad and Idukki districts alone saw more than 3,000 landslides, according to an analysis by Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Kerala section. In 2019, too, Puthumala in Wayanad saw multiple landslides during the monsoon season.

With extensive relief and rescue operations underway in the district’s affected regions, ThePrint explains what climatic, natural and anthropogenic factors contributed to the deadly landslides in Wayanad.

Kerala’s topography

The state of Kerala is situated in the Western Ghats which is prone to landslide hazards, according to the Geological Survey of India (GSI). The elevated slopes, heavy rainfall propensity and the nature of soil cover in the region contributes to this propensity.

The Ministry of Earth Sciences in response to a question in the Lok Sabha in September 2020 said that 13 of Kerala’s 14 districts are “variably landslide prone”. In light of the 2019 landslides, the GSI was also carrying out a “1:1000 scale site specific landslide investigation” at Puthumala in Wayanad district, the ministry informed Parliament.

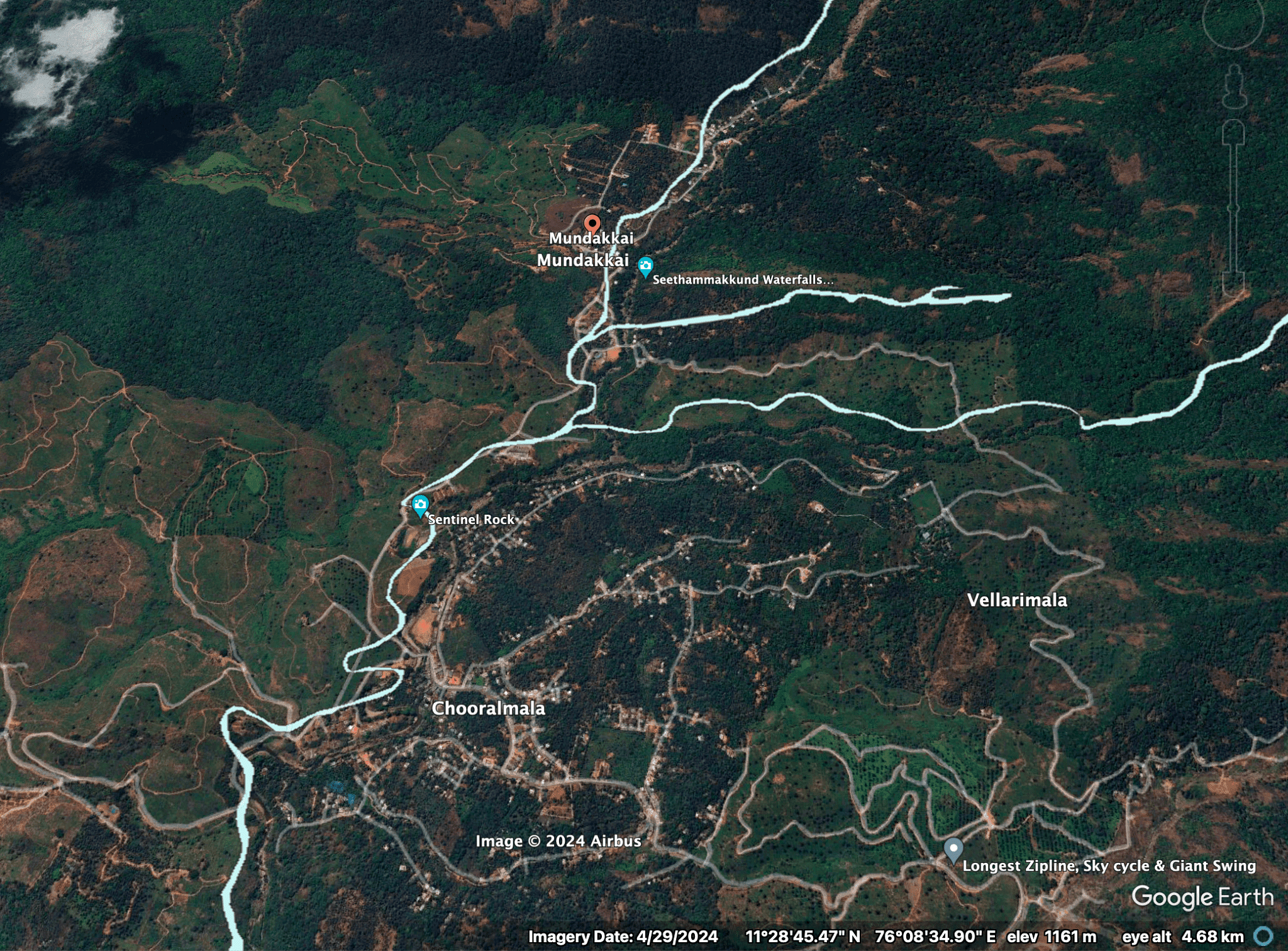

Chooralmala, Vellarimala, and Mundakkai, the three villages worst affected by the recent landslides are all in hilly topographies, with elevations around 900 m above sea level.

They are all situated along Iruvazhinji, a tributary of the Chaliyar river that drains into the Arabian Sea. When extremely heavy rainfall occurs during the monsoon, the river overflows and denudes nearby areas.

All three affected villages are part of the Flood Susceptibility Risk Map created by the Kerala Disaster Management Authority and witnessed flooding and consequent landslides both in 2018 and 2019.

The soil cover in most of Kerala is around 1-3 m thick, and is largely made up of boulders, uncompacted colluvium and laterite, making it easy for it to be transported by human activity. A research paper published in Environmental Geology journal back in 2008 explained how this ‘slope instability’ — which, it said, contributes to landslides in Kerala — is a historical factor exacerbated by anthropogenic actions.

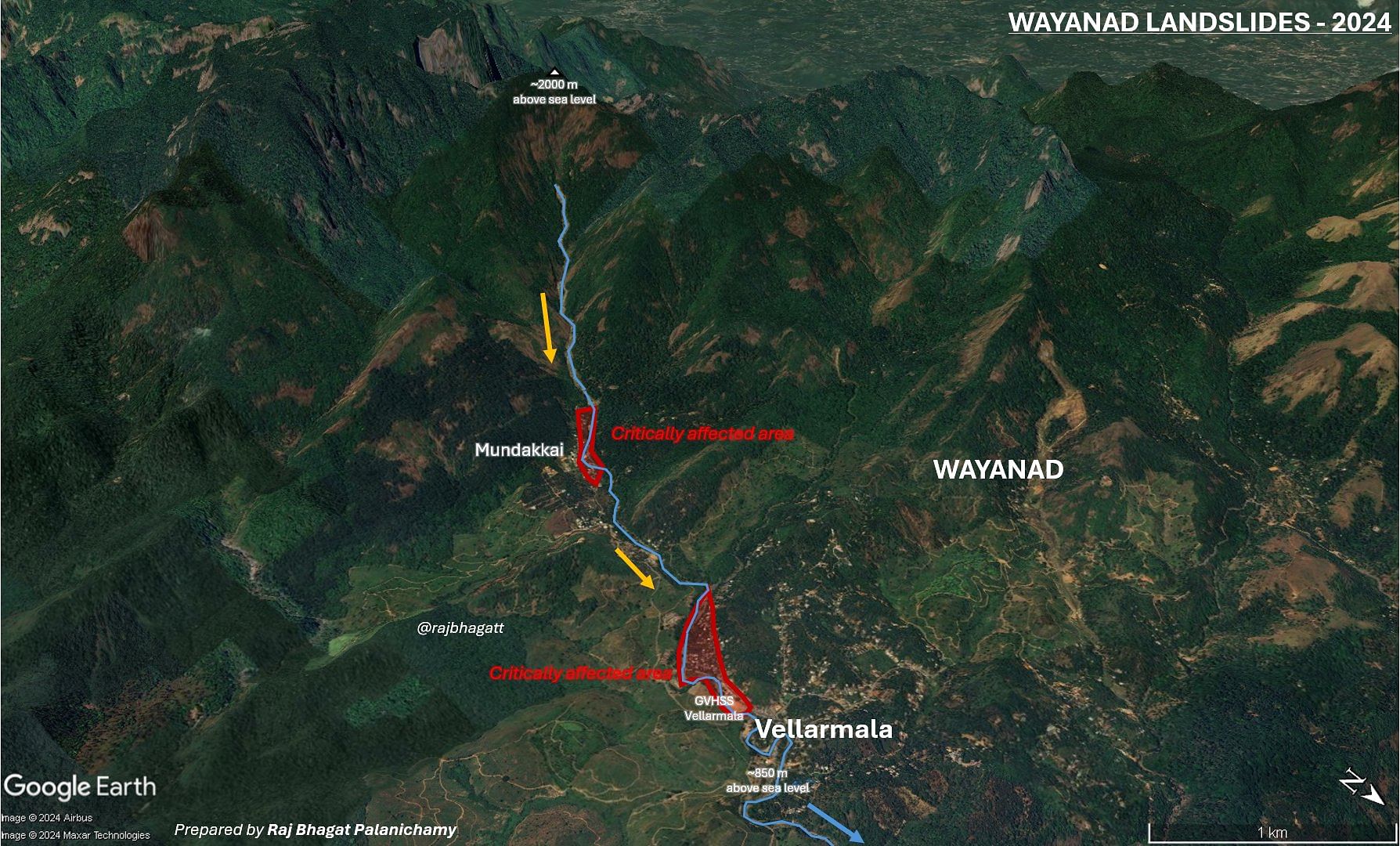

In the case of the recent landslides, another key factor that contributed to the devastation was the velocity of the Iruvazhinji in its path towards Mundakkai and Chooralmala.

Google Earth maps shared by geo-analytics expert Raj Bhagat Palanichamy show that before reaching Mundakkai, Iruvazhinji reaches an altitude of 2000 m, and then drops down steeply to 971 m at Mundakkai, 880 m at Chooralmala, and 850 m at Vellarimala.

This extreme slope lends the river a lot of force and velocity, which when combined with the above-normal rainfall in the last two days, led to flooding and then landslides.

“Roughly half of Kerala are hills and mountainous regions where the slope is more than 20 degrees and hence these places are prone to landslides when heavy rains occur. Landslide-prone areas are mapped and available for Kerala. Panchayats with hazardous areas should be identified and sensitised,” Roxy Mathew Koll, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), Pune, said in a press statement on 31 July.

Anthropogenic factors

While topography is central to understanding factors that make parts of Kerala prone to landslides, floods in 2018 and 2019 gave way to multiple studies that look beyond the natural factors that cause this propensity to landslides.

Being the third most densely populated state in India, Kerala’s population and construction stress also add to conditions that culminate in disasters of such proportions.

“Other than climate change, we also need to evaluate the land use changes and development activities happening over landslide-prone areas. Often landslides and flash floods occur over regions where the impact of both climate change and direct human intervention in terms of land use changes are evident,” said Koll in the press statement.

“At the same time, there have been many severe landslides over regions with minimal land use changes also,” he added.

A 2020 study analysing causative factors of the 2019 landslides in Wayanad and Malappuram highlighted land-use change patterns in these districts that are worth noting.

Plantations, mainly tea and rubber, that dot the slopes of these districts caused “obstructions to the natural drainage system” and multiple ‘dug-up reservoirs’ led to the soil being saturated with water. When heavy rains inundated the Chaliyar river and its tributaries, its width increased from 10 m to 130 m, supported by easy-to-carry soil cover.

The study also found “indiscriminately constructed” houses, many on active floodplains, were entirely destroyed in the deluge. The IEEE Kerala section analysis of the 2018 floods also underlined flouting of building norms and packed constructions in the area.

This time around, too, the landslides led to settlements being completely buried, and bridges connecting arterial towns being broken.

Asked about the rescue and relief operations, Kerala Chief Secretary Dr V. Venu told news agency ANI Wednesday: “The problem they (rescuers) are facing is to cut into the houses which have collapsed and for that, they need heavy equipment. At the moment, we are not in a position to transfer heavy equipment across the river.”

An expert panel led by ecologist Madhav Gadgil had in its report in 2011 pointed out the vulnerability of Kerala’s Western Ghats to indiscriminate construction and quarrying. Identifying 18 Ecologically Sensitive Areas (ESA) in the state, the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel recommended that 75 percent of the Western Ghats needed to be marked as ecologically sensitive zones. This included Mananthavady in Wayanad district.

However, this recommendation, which would have put a stop on mining, quarrying and industrial use of land in ecologically sensitive parts of the state, was not implemented either by the Centre or by the respective governments of Kerala and Karnataka.

“Strengthening infrastructure by investing in climate-resilient bridges and roads will help withstand extreme weather events and facilitate quicker rescue operations,” Dr Anjal Prakash, research director at Bharti Institute of Public Policy, Indian School of Business, said in a press statement dated 31 July, 2024.

“Promoting sustainable land management is also crucial; practices such as reforestation, controlled deforestation, and sustainable agriculture can maintain hillside stability and reduce soil erosion,” he added.

Palanichamy, however, told ThePrint that “at this stage of analysis, we cannot directly attribute the landslides to anthropogenic factors”.

“But could we have taken measures to avoid the damage? Yes, definitely.”

He explained further that going forward, precautions must be taken as to the where, what and how of construction in areas prone to landslides. “The building and development norms for ecologically sensitive areas in Wayanad cannot be the same as those for other areas.”

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: ‘Understand your sarcasm’ — VP Dhankhar & Kharge’s spat in Rajya Sabha over Kerala landslides