Rakhigarhi: On a hot sunny afternoon in April, a family of five arrived at Rakhigarhi, the archaeological site belonging to the Indus Valley Civilisation and located in Haryana’s Hisar district. Their 170 km journey from Delhi filled with anticipation of a time travel, of going back in history, of witnessing evidence of a river India has been looking for over two hundred years — the ‘mightiest of all’, Saraswati.

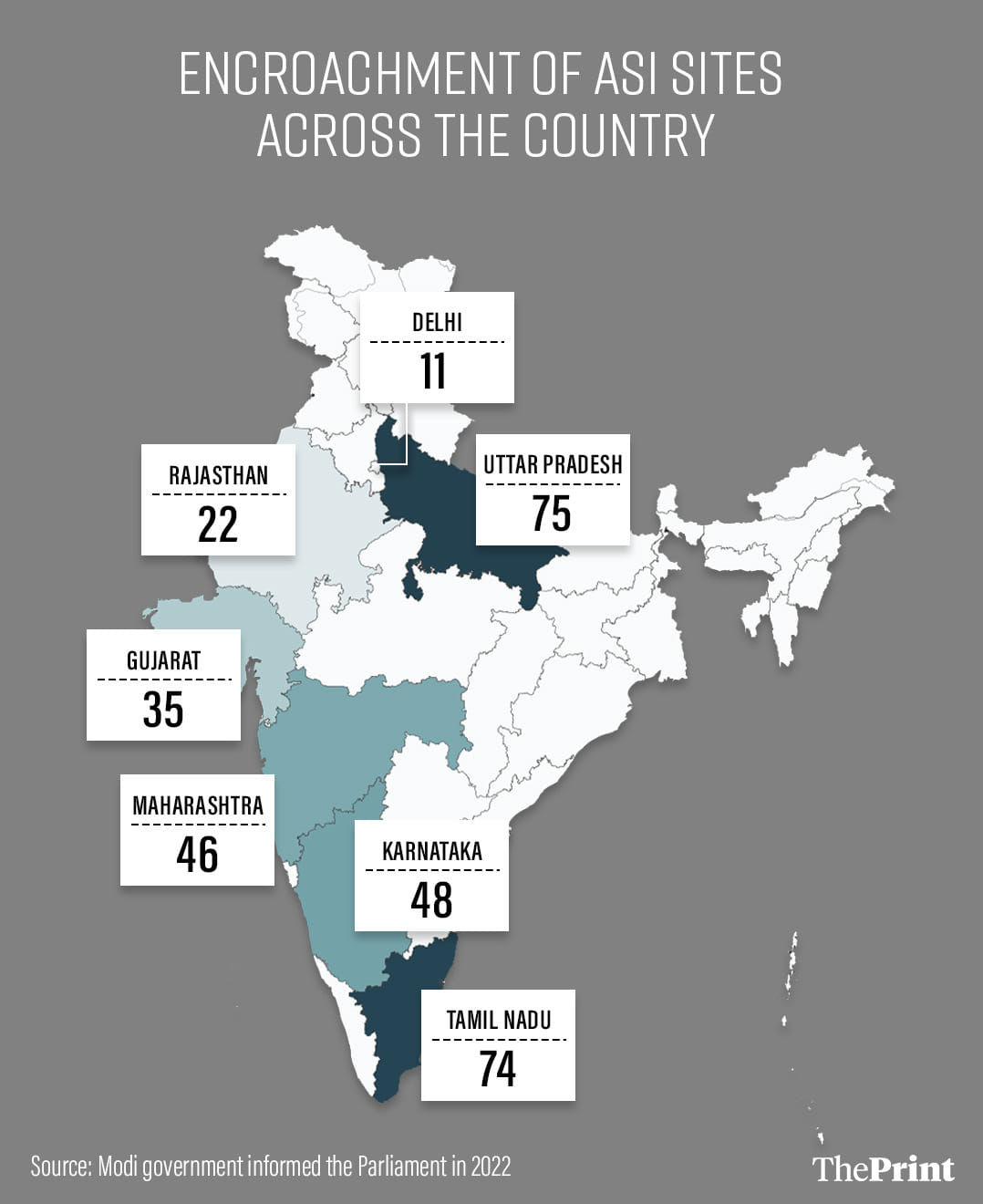

But the excitement ended as soon as they reached the mound periphery, the core of the excavation site. What welcomed them wasn’t proud history but the mundanity of village life — cow dung heaps, stench, and donkeys, buffaloes, and bulls grazing even as the security guards shooed them away. The history at these sites is now captured by dense habitation that in archaeological language will qualify as encroachment. The archaeological sites whose study have the capacity to change the course of India’s history today lie in complete apathy and the project to find Saraswati’s identity, the river that dried up nearly 4,000-5,000 years ago, is sinking with over 60 per cent of the sites reported in the early surveys now lost.

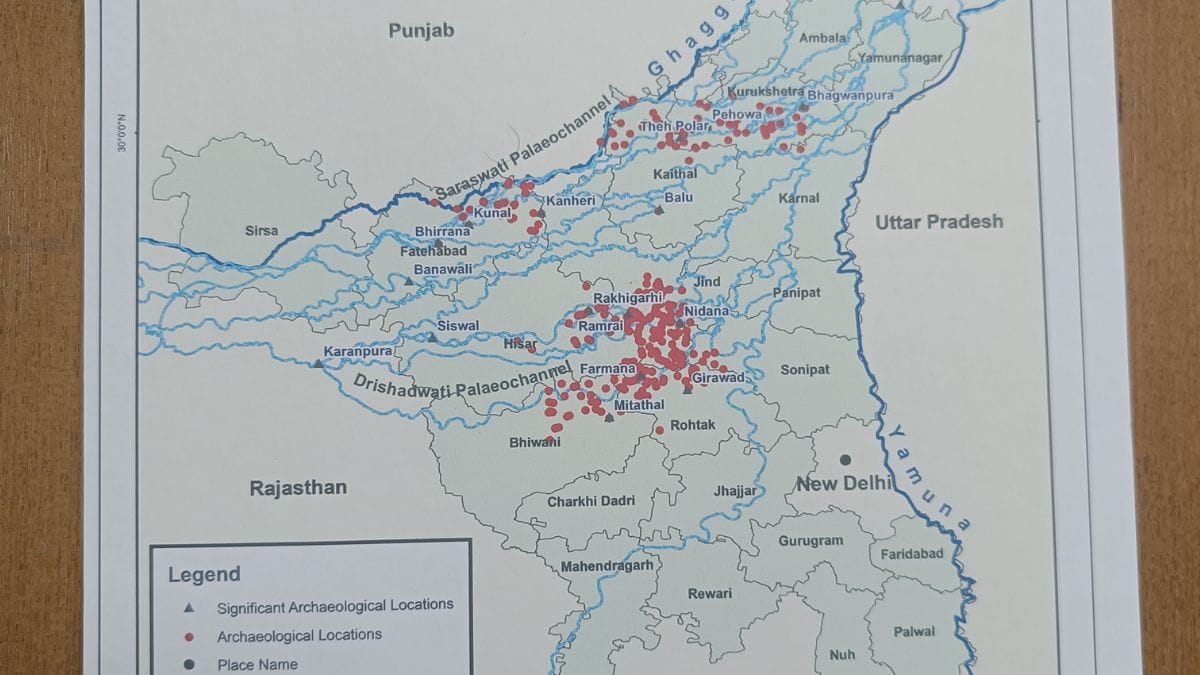

The sites in Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan along the river’s paleochannels may be the biggest archaeological evidence that can establish the Saraswati story but the alarming rate at which the river bed is being lost doesn’t bode well for the band of excavators looking to co-relate the late Harappan period with Vedic period.

And at the heart of this encroachment lies an important question — what is more important, history or livelihood?

“Many generations of ours have been living here. Now it has become a place of national importance, we are happy but who will take care of us? We are the real inhabitants. There is talk of removing us from here. We also have cattle, where will we keep them,” asked Rajesh Sirohi, a daily wage labourer sitting on a bamboo cot beneath a Keekar tree. Sirohi lives at the protected mound number three. The single-storey brick structure is located in the corner of the mound. And any change in its structure requires ASI nod.

Also read: Maharashtra’s holy Indrayani is now ugly green. Everyone’s playing blame game, CM to govt bodies

Legacy vs livelihood

It’s not just the living who are destroying history. Last year, villagers broke the lock of mound number one to cremate a dead body. And it wasn’t the first occasion that saw tussle between local people and the ASI that was trying to stop them.

“People across the world come here to see our village and know our history but that hasn’t changed our lives. Even the government is removing us from here,” said 40-year-old Sirohi, showing the potteries spread on the mound.

But ASI officials see this approach of the local people as a challenge and consider protection of heritage to be a continuous process. “It’s not a one-day matter. Under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act (AMASRA), the state and the Centre have shared responsibility towards protecting these sites. ASI is only entitled to protected sites,” said T.J. Alone, Joint Director General of ASI, adding that it has been seen that mounds have been levelled overnight by villagers.

Despite significant government investment in the Saraswati River project over the last decade, sites such as Bhagwanpura, Tarkhanwala Dera, Daulatpura, Kasithal are completely damaged. Jogne Khera in Haryana has been damaged by floods from the Sutlej-Yamuna link canal. Similarly, sites like Balu, Mitathal, and Baror in Rajasthan, located along the paleochannels of Saraswati, face the risk of extinction.

“The mound is now levelled up for cultivation,” stated ASI website about the Tarkhanwala Dera site in the Anupgarh Tehsil of Ganganagar district of Rajasthan.

The small exhibition hall at the first mound offers insights about the history and recent findings of the site. One of the photographs on a display board showed the distribution of Harappan mounds at Rakhigarhi and the dry bed of ancient Drishadvati river that once flowed adjacent to these mounds. “Bharat ke sanatan sanskriti ko nikat se janne ka avismarniya sanyog (An unforgettable opportunity to know the eternal culture of India closely),” reads a remark in the visitor handbook kept at the hall.

In March this year, the ASI delisted 18 Centrally Protected Monuments as they have been lost to development, encroachment or neglect.

The land belongs to the ancestors of the villagers, Joint Director General of ASI

“We are continuously trying to protect the sites and for that we also alert the villagers to not cultivate the archaeological sites. We have also sent the proposal to the headquarters [ASI] for adding more sites under protection, including Mitaathal and mound number 7 of Rakhigarhi,” said Kamei Atheliu Kaboi, Superintendent Archaeologist of Chandigarh circle.

Land ownership is another factor contributing to damage as some of the archaeological sites are on private land. “The land belongs to the ancestors of the villagers. In such cases, it becomes difficult,” said Alone stressing that people need to be made aware of their archaeological heritage.

Dumping on history

Potteries, bangles among other artefacts are spread all over a piece of large land parcel, on which stands a tubewell structure. A road passes from the land, portions of which are raised, and villagers here throw dead animals and garbage that leaves an unbearable stench every now and then.

Farmers use this land to collect their crops. Local people have tied red clothes on a Keekar tree, below which a raised platform made of bricks has pictures of Lord Hanuman and Radha Krishna placed. It is not any other village backyard. The land is the historical mound at Balu located barely 1.5 km from the actual village settlement and one of the most prominent archaeological sites spread along the paleochannel of the Saraswati river. Balu, one of the smaller sites in the Kaithal district, is just 55 km from the Rakhigarhi. It is now on the verge of extinction with most portions of the mound now razed.

The site was excavated in 1979 and reveals the 4.50 metre thick deposit of Harappan cultural sequences. Now a large part of the site has been cut into an agricultural field and farmers cultivate wheat here.

Four decades ago, the site was the place of excitement when excavated and ASI had hired villagers.

“Back then, we only knew about the mound, unaware this place has a history of thousands of years. Villagers had surrounded the excavation site,” recalled 82-year-old Rajendra Kumar, recalling the excavation of 1979.

Lying on a cot at his village home, Kumar said that excitement around the site died long ago.

What has also worked against the Balu site is that it doesn’t fall under the protected category.

“This mound is amid agricultural fields, away from the village. Over the decades, both its height and area have been decreasing. Those who have fields next to the mound are expanding their sowing area by cutting into it,” said Kumar.

Also read: Bumper crop, bitter harvest—Byadgi chilli market riot is a warning bell for Karnataka

Conservation steps

Saraswati has been mentioned more than 70 times in the Rig Veda as the “greatest of mothers, greatest of rivers and greatest of goddesses”. Various studies conducted over the years claim it originated from the Bandarpunch glacier in Garhwal, flowing past Adi Badri in Himachal Pradesh and traversing Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan before reaching the sea at the Gulf of Khambhat in Gujarat.

The river went extinct thousands of years ago. Now its evidence is on the same path. This despite the Haryana government heavily investing in the search of Saraswati. In 2017, the state government established the Centre of Excellence for Research on the Saraswati River (CERSR) in Kurukshetra University.

Various state agencies are working on the revival of the ancient river system, but nothing is being done to conserve the archaeological sites along the dried banks of Saraswati. While the identification of the paleochannels was a step forward, the encroachment of the mounds is in a way undoing the work of the excavators.

“Saraswati river has always remained in the memory of the people of Haryana. But the change came after 2014 when we started focussing on the identification of the paleochannels of this river system. As of now, we have identified a 3,200 km route of this river,” said Professor A.R. Chaudhri, a Geologist and Director at CERSR.

The Archaeological Department of Haryana admitted that the Balu site was to be fenced and provided with public amenities but nothing happened on the ground. Now the authorities too seem to have made peace with it and their focus has shifted to key sites.

“We have to work painstakingly to cover all the sites but now our focus is on the most important archaeological sites. We are following the hierarchy from bigger to smaller sites,” said Amit Khatri, an IAS officer and Director of Archaeology and Museum Department, Haryana.

Khatri said the department is working with a three-pronged approach. “Expanding conservation projects, excavating landmark sites such as Rakhigarhi and Kunal, and trying to include new technology like GPR (Ground-penetrating Radar) survey to maximise the input,” he said, adding that the at the same time, the department is trying to popularise these sites through heritage tours that will insure they do not remain in silos.

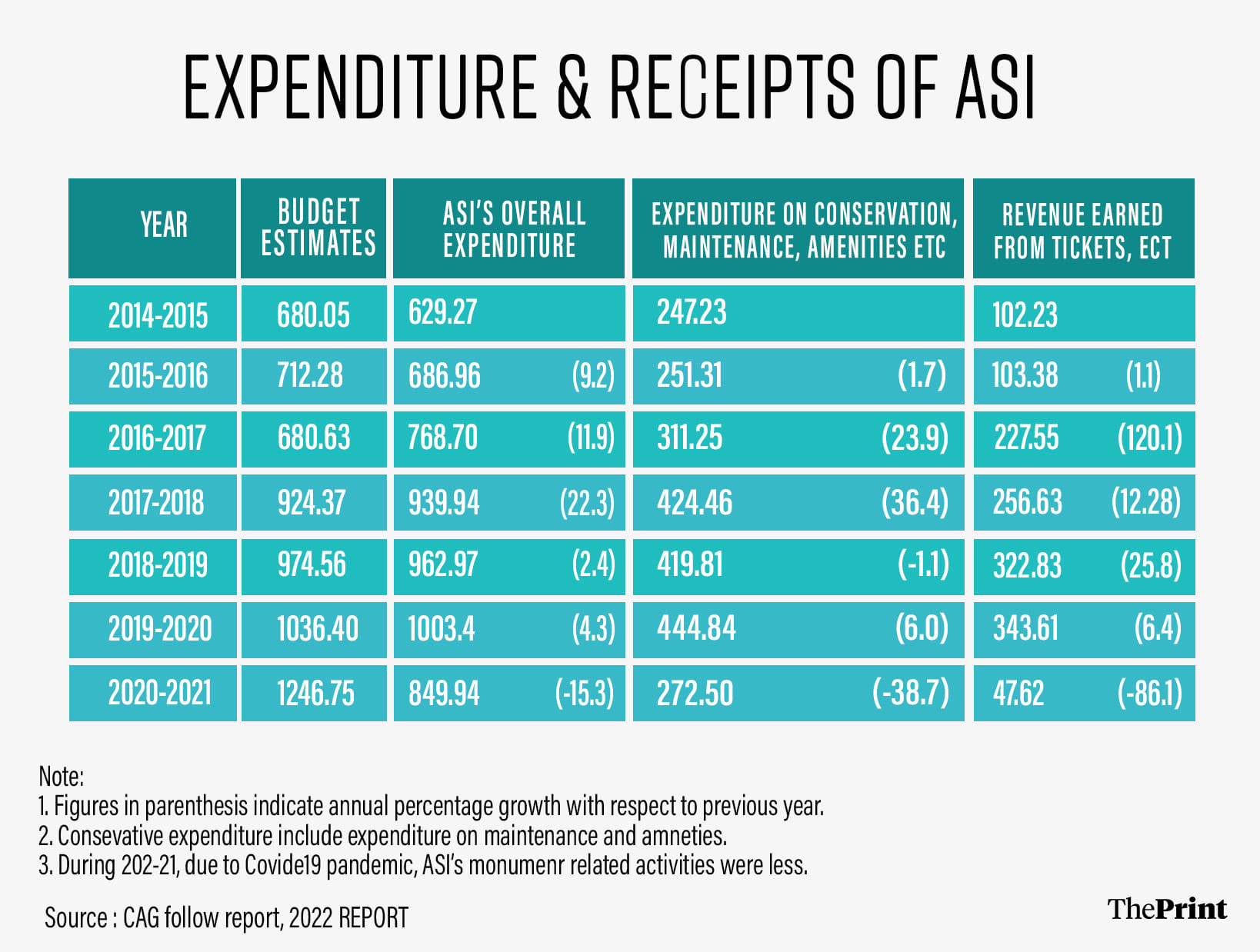

Last year, a Parliamentary panel also suggested changes in the AMASR law to tackle the encroachments at archaeological monuments and sites. “Despite recommendation, no coordination and monitoring mechanism was established at Central or Circle levels to check the incidents of encroachment,” CAG stated in its 2022 follow up report titled Performance Audit of Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities.

Finding Saraswati

Big boards installed outside many villages in Yamuna Nagar, on the Haryana-Himachal border, show the path of Vedic Saraswati. For many local people, Saraswati is a mythical river. But for villagers of Haryana, it’s a matter of faith. Excavation at Mugalwali village (near the river’s origin) in 2015 caught attention — excavators found sediments of a river system. Chaudhri’s team dug up this site with help of MNREGA workers.

A decade has passed but villagers still remember the day with fondness, cherishing how their village had attracted national headlines.

“We are just a few kilometres away from the origin of Saraswati. All we know is that it dried in the past but still there is a route of the river from our village,” said Amit Kumar, resident of Mugalwali. He said this river should revive as this is part of our civilisation. Kumar has travelled to Adi Badri, which is now a tourist attraction for many.

Faith, mythology, government agencies and hordes of supporting archaeological evidence notwithstanding, questions continue to be asked on the need for the revival of the lost Saraswati and the money spent.

Senior archaeologists questioned the government’s priority and said spending a lot of money is not important but doing meaningful work is crucial. “We speak a lot about our glorious civilisation but when the time comes, the government doesn’t pay much attention. On one side, we are behind tracing the lost river. On the other hand, the sites along this river are being continuously damaged and encroached,” said a senior archaeologist part of the government’s advisory committee for multidisciplinary study on river Sarasvati, on the condition of anonymity.

But Chaudhri has a clear answer to the Saraswati cause pasted on the wall outside his office — “To find the cultural antiquity of Indian civilisation, deep aquifer identification and placer mineral deposits.” And the river is important for our civilisation, he said.

Sitting in his CERSR office at Kurukshetra University and surrounded by photographs of archaeological sites and paleochannels of the Saraswati, Chaudhri claimed to have identified all the paleochannels of the Saraswati river system. In 2015, he started digging from Mugalwali village of Yamuna Nagar district, just 12km from the origin of Saraswati at Adi Badri.

“Paleochannels are being discovered on the basis of moisture in the ground. We have also used remote sensing techniques,” said Chaudhri, adding that these channels can be used to mitigate water scarcity by diverting the excess water during floods. The Yamuna Nagar district is flood-prone.

According to his findings, the majority of the archaeological sites in Haryana like Siswal, Rakhigarhi, Bhirrana, Kunal, Balu, Banawali are present at a radial distance of less than 500 metre from the paleochannels of Saraswati river.

Also read: Jaipur, Agra, Lucknow got big status with metros. It’s all pride, no profit or passengers

A grand Museum in making

Just a few metres from the mound number one at Rakhigarhi, work is going on to build a huge museum. A group of men and women give final touches to the project. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the project as part of her 2020 budget.

But it’s not the first attempt to take history to the common people and capture their imagination with a past that may benefit the politics of the future.

In 2002, the Vajpayee government proposed the Visitors Information Centre (VIC) at the archeological sites along the Saraswati river. But only a few — at Kalibanga, Ropar, Thanesar — could see the light of the day. “State government should work rigorously for the infrastructure arrangements at these sites. Only bigger sites are given priority which results in a loss of smaller archaeological sites,” said a Superintendent Archaeologist on condition of anonymity.

The site at Bhagwanpura village, one of the smaller sites, just 19 km of Kurushetra, suffered due to this line of administrative thinking. The site was discovered by veteran archaeologist R.S. Bisht and excavated by J.P. Joshi during the emergency years. The excavation revealed the link between the Harappans and the civilisation that used Painted Grey Ware (PGW).

Babu Ram, a resident of Bhagwanpura, recalled when J.P. Joshi excavated the site in 1976. Ram, now in his 80s, said people were happy then as the ASI offered Rs two per day as daily wage. “We saw the Re 1 coin for the first time.”

Today, few from the village can recall that nearly 40 years ago, just 350 metres from their hamlet, a 25-foot mound, ready to take you into the knowledge of Saraswati. The farmers now grow wheat at the site with a tube well located nearby.

“Within a few years of digging, the landowners started cutting the soil and making fields. People used to climb from one side of the mound to the other. Now no one can even say that there would have ever been a mound here,” said Babu Ram.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)

Where is Saraswati river…

Fake river fake history…