Patna: Until recently, the first floor of Dumraon Palace at Dak Bungalow Chauraha was better known for masala dosas at Sagar Ratna. But this Fraser Road address is now serving up a dose of history.

Three months ago, the space reopened as Planet Patna, one of the city’s first private museums, founded by Aditya Jalan, a member of a Marwari business family known for their patronage of the arts. The museum taps into Patna’s burgeoning interest in its layered history, with paintings and archival documents on the city’s oldest schools, libraries, hospitals, and theatres. It also showcases Patna Kalam, the painting tradition that flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries across Patna, Danapur, and Ara.

Patna has become a city of museums. Beyond the grand overarching institutions such as Patna Museum and Bihar Museum, which tell the epic tales of dynasties and civilisations, it is turning its attention to smaller community museums. Focusing on the Bihar Regiment’s military heritage to 19th-century Patna to one documenting Gandhi’s Bihar connection, some new museums are already open and others are in the works.

“It is making local history great again. The new museums are a reimagining of how people engage with museums,” said Dr Azfar Ahmad, a Delhi-based museologist who helped turn the 6,000-square-foot Fraser Road commercial space into Planet Patna.

Pamphlets are being distributed, and hoardings are going up about the newest museum on the block. Planet Patna has also mapped out a heritage walk that includes government-run museums. The idea is to fold the new private museum into a wider museum circuit. It’s a revival of the Jalan family’s legacy as curators.

Their Qila House—better known as Jalan Museum—was one of Patna’s attractions and could be visited by appointment until a family dispute led to it shutting down in 2020.

Built in 1919 by Radha Krishan Jalan on land once part of Sher Shah Suri’s fort, the Ganga-facing museum displayed treasures he collected: Birbal’s silver dining set, Napoleon III’s bed, Tipu Sultan’s ivory palanquin, King Henry II of France’s cabinet. The stately mansion is still occupied by extended family members, but its museum halls are locked and its condition has suffered in the years of wrangling. Memories of its glory days inspired Aditya Jalan to start Planet Patna.

Unlike many British-era museums, which often carried a sense of heen bhavna or inferiority about one’s past, the curation of new museums evokes pride

-Ratneshwar Mishra, historian and author

“The idea was conceived when we celebrated the hundred years of Qila House in 2019. While going through trunks of neatly chronicled archives, I discovered rare letters and paintings that deserve to be seen by the people of Bihar,” he said.

These personal letters of RK Jalan captured long-forgotten vignettes of colonial Patna. One described the Bihar Young Men’s Institute of 1899, where students paid two rupees a year to play table tennis. Another documented the transformation of the Temple Medical School into the Prince of Wales Medical College in 1925, now the Patna Medical College and Hospital. During World War II, the institution played a vital role in treating the wounded.

Not far from Dak Bungalow Chauraha, another museum dedicated to the Bihar Regiment is set to open in October. Formerly the Maurya Museum, it is being reconstructed under the watchful eye of Colonel Tejinder Hundal at Danapur’s Bihar Regimental Centre. It will house reminders of the regiment’s history—from the original warrant issued to Mangal Pandey in 1857 to Ashokan swords and armour, a 1798 pistol, British military orders from 1791, and the surrender certificate from the Goa Liberation of 1961.

The list is growing. The century-old Patna Museum has been given a new life with glossy interactive galleries. The 1990s Taramandal has received a futuristic makeover. Bapu Tower’s copper façade has become a landmark since it opened this year. The Dr APJ Abdul Kalam Science City was inaugurated by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar on 21 September and work on the Digital Legislative Museum, which will chronicle Bihar’s political history, is underway.

Also Read: ‘Ram needs all nine emotions’. Dance-drama RAM is 68—Nehru, Vajpayee to Modi’s India

AI, holograms, and ‘pride’ reawakened

It was a day of firsts for Priyanka Kumari, a 16-year-old student from a government school in Rohtas district. On 29 August, she and thirty classmates boarded a bus under the Mukhyamantri Bihar Darshan Yojana, a state scheme that brings schoolchildren to Patna’s museums.

The ride took them past traffic lights and flyovers, across the towering Ganga bridges, and past the iconic Gol Ghar’s dome, before pulling up at Patna’s twin institutions: the Bihar Museum and the newly renovated Patna Museum.

Of the two, Bihar Museum has recast itself as a cultural hub—often called the “Indian Habitat Centre of Patna”—where the city’s elites and intellectuals gather. The older Patna Museum, meanwhile, is attracting a new generation of the old crowd—busloads of school students and families discovering its revamped exhibits. The older generation still calls it a Jaadughar or Ajaibghar, a mysterious place full of treasures locked in glass cases. But for Kumari and her friends, dressed in matching blue salwar kameez, the Patna Museum is an immersive, hands-on experience.

In the new Ganga gallery, they walked on glass panels where the river flowed beneath their feet, emerging from a 3D image of Lord Shiva’s jata (matted locks). A sensor sprayed water with every step, while digital fish darted away as though startled by their presence. The gallery itself unfurled like the river charting its 445-kilometre journey through Bihar’s seven cultural regions—Shahabad, Magadh, Kosi, Ang, Tirhut, Mithila, and Seemanchal.

“It’s thrilling,” Kumari exclaimed, pausing before terracotta figures, sling balls, and pottery tucked behind a mud-textured wall designed to resemble an excavation trench.

“The layers of dig you see here show how we unearth antiquities from different periods,” explained curator Dr Ravi Gupta. As he spoke about the Mauryan period, the girls began counting how many ‘grandparents of grandparents’ ago the museum artefacts had been made.

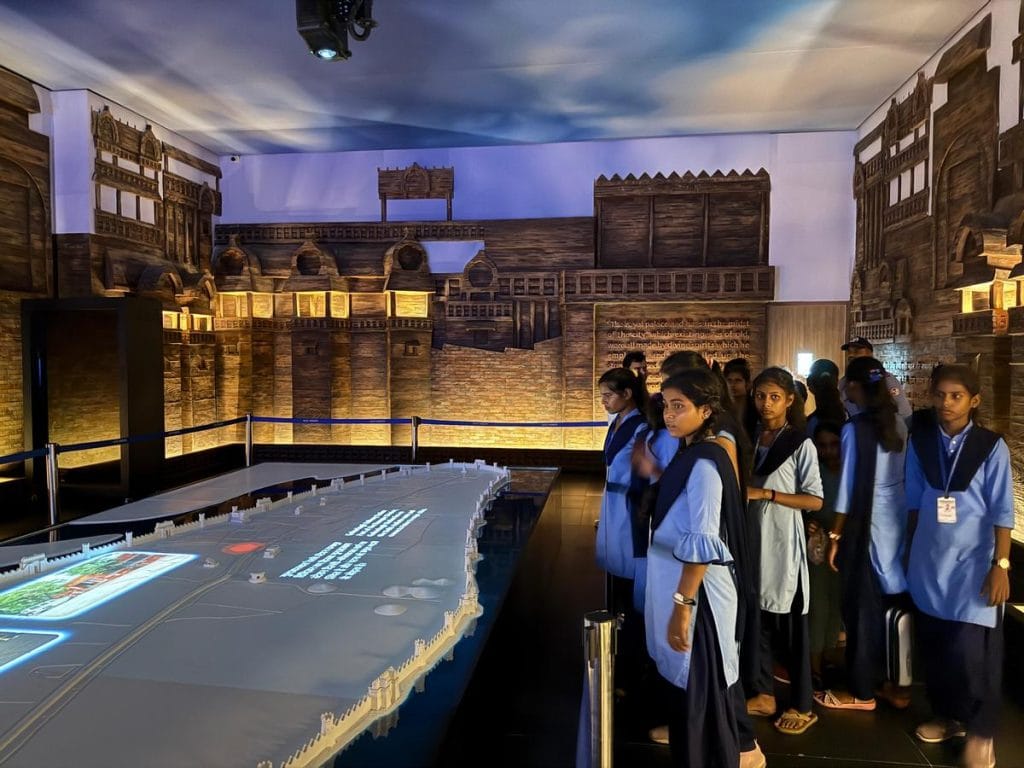

The Patli Gallery is another new addition, dedicated to the capital of the Magadha kingdom. Its centrepiece is a 16-foot digital model of ancient Pataliputra. A hologram of Chanakya stood beside it, animated on an AI-powered screen. When Kumari’s group spoke to him in Bhojpuri, Chanakya replied in the same language. For a moment, the students found themselves talking across time.

“For a museum to engage young minds, it has to keep up technologically. Without AI integration, this would just be a typical old government museum,” said Sunil Kumar Jha, deputy director of Patna Museum.

These places aren’t just a collection of relics or elite contemporary art in metropolitan centres, but engaging and inclusive

-Anjani Kumar Singh, nodal officer for Bihar Museum

Even as old favourites get an upgrade, new museums are elbowing their way into the city’s cultural landscape.

The Rs 48 crore Digital Legislative Museum, which is under construction on the Assembly premises, will archive a century of Bihar’s legislative history, from its first speakers and CMs to landmark debates and decisions.

Then there’s Bapu Tower, which has been open since February, its six copper-clad storeys rising 120 feet above Gardanibagh. On the ground floor, a revolving theatre screens a short film on Gandhi and Bihar before leading visitors into five storeys of installations, replica huts, maps, and modern art galleries.

“We are announcing scholarships of Rs 15,000 for three months to support scholars researching Gandhi, along with internships for college students,” said Vinay Kumar, director of Bapu Tower. It has also begun a lecture series, with the first speakers including Gandhi Peace Foundation chairman Kumar Prashant, Gandhi Sangrahalaya secretary Dr Razi Ahmed, and former Patna University principal Dr Tarun Kumar.

Historians and scholars say the new museums promote an awakening of dormant cultural pride, making them an uplifting experience.

“Unlike many British-era museums, which often carried a sense of heen bhavna or inferiority about one’s past, the curation of new museums evokes pride,” said historian and author Dr Ratneshwar Mishra. “For Patna, and Bihar too, this is a heartening change.”

But it’s not just about looking back and reclamation. The scientific temperament is getting a boost as well. On Sunday, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar inaugurated an ambitious science museum.

Spread over 22 acres in Rajendra Nagar—acquired in 2019—the APJ Abdul Kalam Science City has been built with Rs 889 crore in funding. The museum has five galleries and 269 exhibition models, along with a 4D theatre and a 500-seat auditorium. Two of the galleries are currently open to the public.

“This Science City has become a modern centre of science and innovation that will attract people of all age groups,” Nitish said at the event.

A blueprint for the museum movement

Encroachment, lawsuits, and the land mafia often get in the way of ambitious projects in Bihar. But the museum drive started with Chief Minister Nitish Kumar himself. In 2010, during a visit to Patna Museum, he discovered that up to 80 percent of the state’s artefacts were locked away in trunks for lack of display space. Former chief secretary Anjani Kumar Singh describes this as the spark that led to the idea of building a new museum, with him as nodal officer.

The first success was Bihar Museum, which came to life in 2017.

“We wanted to build it with narration, storytelling, and something that invited you to return,” said Singh, director general of the Bihar Museum. The project gave the government a model for acquiring land, navigating PILs, allocating funds and bringing in curators.

“Once Bihar Museum became functional, many complementary institutions began to take shape. We needed a template, and now we had that,” he said.

Built at a cost of Rs 500 crore, it is the flagship institution of Bihar’s museum wave. Located on Bailey Road, it stands as an example of Japanese minimalist design and has become a hub for the arts. Every two years it hosts the one-of-a-kind Bihar Biennale of Museums, founded by Singh to put Patna on the national cultural calendar.

This year is the third edition of its Biennale, from August to December, with artists, academics, and curators from all over the country visiting. As part of the programme, it also mounted a Mexican gallery in the neighbouring Patna Museum.

The fact that the state allocates Rs 2 crore every month for Bihar Museum’s maintenance shows how much it prioritises its position

-Ranbeer Singh Rajput, Bihar Museum deputy director

On a rainy August afternoon, 16-year-old Soni Kumari, a visually impaired student from AntarJyoti Balika Vidyalaya in Patna, wandered into the Mexican Gallery with 20 schoolmates. She lingered at two tactile works by artist Eva Malhotra, which invited visitors to “please touch”. Titled The Time Keeper, it was a textured rendering of stars and galaxies. As Soni and her friends ran their fingers across the canvas, some got visibly emotional.

“It feels like we have seen the galaxies and stars,” Soni said.

For Singh, what sets Patna’s museums apart is that accessibility is part of the agenda.

“These places aren’t just a collection of relics or elite contemporary art in metropolitan centres, but engaging and inclusive,” he said.

Footfalls, busloads, museums on wheels

When Bihar Museum set its ticket price at Rs 100 per adult, with subsidies for students and children, sceptics said it was too steep for a state with a low per capita income. But the crowds have proved otherwise. The museum now sees over 2,000 visitors a day.

The appetite has spread. Many are willing to pay for cultural edification, especially now that it comes with engaging, interactive displays.

At Patna Museum, entry is Rs 50, set to rise to Rs 100 once all the new galleries are functional. Even now it sees 700 visitors daily, and up to 1,200 on peak days. Bapu Tower, built with Rs 129 crore to mark the centenary of the Champaran Satyagraha, averages 500 visitors a day and hits 1,000 on weekends. Spread across seven acres, the biopic museum documents through 3D and visual displays the subaltern history of Bihar through the stories of men and women who hosted Gandhi in Champaran.

The revamped Taramandal, reopened in 2024, charges Rs 100 a ticket and Planet Patna has set the same price, although these venues still have relatively modest footfalls.

The museum movement has been a multi-department enterprise. In execution, the Building Construction Department (BCD) played a critical role.

For a museum to engage young minds, it has to keep up technologically. Without AI integration, this would just be a typical old government museum

-Sunil Kumar Jha, deputy director of Patna Museum

“Bihar Museum, expansion of Patna Museum, Bapu Tower, Science City, Vidhan Sabha Digital Museum—BCD has executed these projects,” said Kumar Ravi, Bihar building secretary. “It has played an important role in conceptualising, designing, and executing the civil infrastructure of these state-of-the-art projects, acting as the nodal agency.”

But the state isn’t stopping at building museums. It also wants to make sure people are reaching them. Children are now being ferried in buses to museums through the Mukhyamantri Bihar Darshan Scheme under the education department. The Patna Municipal Corporation has been roped in too, transporting children from more than a hundred urban slums.

And sometimes the museums themselves have wheels. In 2023, a mobile museum was set up at the Sonepur Mela, where more than 20 lakh visitors caught a glimpse of artefacts usually far out of sight in Patna.

“There would still be people left behind who can’t just come out to the museums in the state capital. So we experimented with mobile museums,” Anjani Kumar Singh told ThePrint.

Also Read: Triveni Kala Sangam in Delhi is 75. Its family is building an archive

Flowing funds, minimal red tape

Even as new museums crowd the Patna skyline, the two venerable old institutions are also still very much a work in progress. And it’s all happening without the red tape that usually binds such projects.

The Rs 158-crore renovation of the Patna Museum, built in 1917, is proceeding without a hitch, with craftspersons from Rajasthan restoring its red-and-white walls, chhatris, domes, and jharokha-style windows.

“The emotional connection Biharis have with the old Jadughar was kept in mind, as generations have visited it over the past century,” said deputy museum director Jha.

When he asked for an additional Rs 15 crore to build two conservation labs, the money was cleared without delay. Now 25 specialists, from conservators to technicians, work in shifts repairing artefacts.

“We call them ‘metaphorical clinics’ where experts diagnose cracks, prescribe treatments, and operate on century-old wounds,” Jha said. Manuscripts, too, are being scanned, catalogued, and digitised in these labs.

Now a 1.5-kilometre ‘world-class heritage’ tunnel is being built at a cost of Rs 542 crore to connect it to Bihar Museum, its younger cousin. It’s a subway between two eras: the Patna Museum keeps the post-1764 collection, while Bihar Museum houses the earlier artefacts.

“The fact that the state allocates Rs 2 crore every month for Bihar Museum’s maintenance shows how much it prioritises its position,” said its deputy director, Dr Ranbeer Singh Rajput.

Many of Patna’s museums are run by autonomous societies under the Art and Culture Department, giving them more flexibility and freedom from red tape than museums under direct state control. Both Bihar Museum and Patna Museum are managed by the Bihar Museum Society, constituted under the Societies Registration Act.

For Anjani Kumar Singh, the real test is whether the new crop of museums is able to replicate what Bihar Museum managed to do—get long-term buy-in from the people and wider recognition.

“Just like we have done with the Bihar Museum, the rest have to stand on their own by engaging with communities. This will make them more than museums.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)