PastForward is a deep research offering from ThePrint on issues from India’s modern history that continue to guide the present and determine the future. As William Faulkner famously said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Indians are now hungrier and curiouser to know what brought us to key issues of the day. Here is the link to the previous editions of PastForward on Indian history, Green Revolution, 1962 India-China war, J&K accession, caste census and Pokhran nuclear tests.

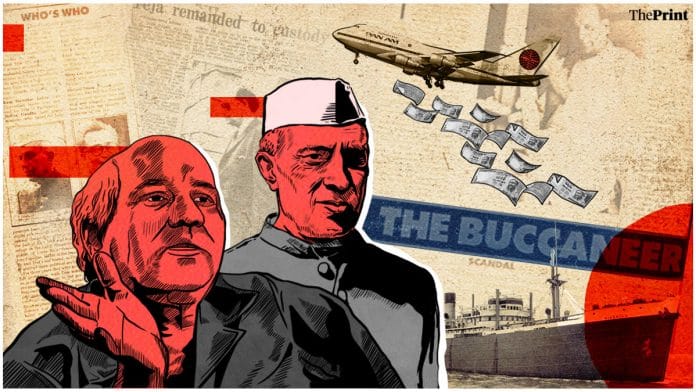

Jayanti Dharma Teja had Lutyens’ Delhi wrapped around his finger. He was a scientist, a scholar, a schmoozer, a shipping magnate, and a close friend of the Nehru-Gandhi family. That’s before the scandal broke. And what a scandal it was.

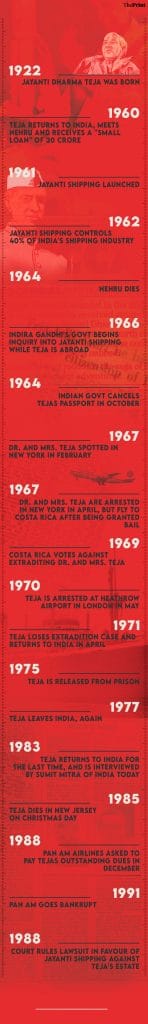

It all started in 1960, with a party hosted by parliamentarian M. Thirumala Rao. One of the guests was Teja, a young man with Andhra roots who was relatively unknown in Delhi and had just returned to India after pursuing a prestigious science career abroad.

As the guests, which included ministers and MPs, circulated and chatted at Rao’s party, someone promised to introduce the urbane and ambitious Teja to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

The introduction would change Teja’s life. Two days later, Nehru sent for Rao and asked him, “What about this young man?” Rao answered to the best of his ability: “I know him, I know his family, he seems to be a decent man.”

That was enough for the prime minister.

Nehru was a socialist who generally kept big, bad business at arm’s length, except for his on-off relationships with the likes of J.R.D. Tata, G.D. Birla, and Ramkrishna Dalmia — but Jayanti Dharma Teja was different.

To Nehru, Teja represented a glittering symbol of a polished, erudite, wealthy New India. With a loan of about Rs 20 crore, no small sum in 1960, Nehru elevated Teja to a tycoon who promised to revolutionise India’s shipping industry. It’s a different matter that Teja wasn’t even that keen on shipping.

The loan eventually turned into a lengthy rap sheet, and Teja absconded with pockets full of money he owed the government and his business partners — always one step ahead of the Indian authorities as they chased him across three continents. Before Vijay Mallya, Nirav Modi, and Mehul Choksi, there was Jayanti Dharma Teja — and no one quite like him since.

Yet, even as suspicions about him grew over the years, Teja became so close to the Nehru-Gandhi family that Nehru was entrusting him with top-secret diplomatic missions. Teja also reportedly gifted Indira Gandhi a mink coat, and allegedly financed Rajiv and Sanjay Gandhi’s stay in London. One former employee even overheard him asking the younger Gandhi at breakfast: “Sanjay beta, paisa chahiye? (Sanjay, son, do you need money?)” So influential was Teja that a British court asked him if he was being groomed as “successor to Nehru”. No comment, he answered.

Even though Teja always maintained his innocence, his reputation as a friend of the Nehru-Gandhi family put a target on his back. He fled the country when accused of financial crimes, but continued his international hobnobbing.

His flight across the world set the blueprint that fugitive millionaires have used for decades, including trying and testing techniques like political name-dropping, using diplomatic passports, and splitting time between London, New York, and a banana republic.

“I think Nehru’s detractors used me as an excuse to whip up a scandal,” Teja said in a 1983 interview. “There is no weapon which is more powerful than scandal.”

Also Read: Is Modi a better builder of India or Nehru? They aren’t all that different

Almost family to the Gandhis

Teja knew how to make and keep his friends in high places. He would shower the Gandhis with gifts, throw parties for members of Parliament on his cruise ships, and had the Costa Rican president in his back pocket.

“Much before Vijay Mallya and Nirav Modi, whatever you could imagine Indian capitalists to be, it would be him,” Ruhi Khan, a journalist and co-author of the book Escaped: True Stories of Indian Fugitives in London, said. “Both Teja and Mallya were very ambitious, and had this desire to make India touch the skies. In Teja’s case, the oceans.”

Teja came from a Brahmo Samaj family of well-connected freedom fighters and liked to claim that MK Gandhi named him ‘Dharma’. He’d also tell people that when he was a child, Nehru was a frequent caller at his house. When Teja returned to India in 1960 after studying and working abroad, he was reintroduced to the who’s who of Independent India.

And with that, Teja’s fortunes changed. Nehru was looking to develop India’s shipping industry, and chose Teja as the man to help him to do it. Thus, the Jayanti Shipping Company was born, and with a princely loan of Rs 20.25 crore in February 1961, the Nehru government formally stationed Teja at the helm of the shipping industry.

He was charismatic and commanding, quickly becoming the quintessential Lutyens’ social animal of the time. But his close friendship with the Nehru-Gandhi family came at a price: His fame and fortune were tied to the largesse of the Nehru family.

“Some people had issues because of his access to Teen Murti,” veteran India Today reporter Sumit Mitra, who profiled Teja in 1983, said. “They cooked up all sorts of stories, uttered in such a manner that it was believable.”

There were more than enough believable rumours about him: that he bought Indira Gandhi a mink coat and a necklace, and that he also paid for the family’s foreign vacations, some of which took place at his Villa Cashmere in Cannes. Teja’s former employee testified that he financed Sanjay Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi’s stay in London and that he wanted Sanjay to become an automobile mogul. He allegedly helped Sanjay Gandhi get his internship at Rolls-Royce.

“An awful lot of hogwash has been talked about my relations with that family,” Teja said later, in 1983. “The rumours about my acquaintance with the Nehrus being remunerative in any way were all concocted by the same sources that sought to harass me and hound me out of three continents.”

Also read: Kissa Kursee Ka: A parody that sent Sanjay Gandhi to jail and laid bare Indian politics

From science to shipping to socialising

What’s ironic is that Teja never wanted to be a shipping magnate, or at least so he said.

“I must tell you that I did not want to start Jayanti Shipping Corporation. It is Mr Nehru who thrust it on me. At that time, Jayaprakash Narayan warned me against coming to India as a rich man, but Nehru prevailed on me,” Teja told Sumit Mitra in 1983. “It is Mr Nehru who suggested that I give him a brief report on how to sharpen the image of Indian shipping. That was 1960.”

And as media outlets ran headlines asking “Has Jayanti Done It?”, he did do it. He brought on board Dutch engineers and Japanese giant Mitsubishi, and by late 1962 Jayanti Shipping controlled 40 per cent of India’s shipping. Buoyed by this swift shipping success and the Nehru firewall in 1963, Teja began attempts to diversify into the thermal power industry.

“He drew upon his standing as somebody who is the prima donna of India’s expanding industry and a member of India’s elite,” journalist and historian Danish Khan, co-author of Escaped: True Stories of Indian Fugitives in London, said. “He was looked upon as a mover and shaker of India. What harmed him was his ambition. He wanted to do too many things.”

Born in 1922, Teja was a 6ft 4 intellectual who left an impression on everyone he met. He had a PhD in astrophysics and said he worked with physicist Enrico Fermi, known today as the architect of the nuclear age. He also claimed he spent time with Einstein and Oppenheimer, and was a visiting scientist at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Geneva.

Teja’s family too expounded about his scientific achievements in an essay published in a book about Behrampur (where Teja was born) called The City of Brahma by Dr Poodipeddi Venugopal Rao. This essay claimed that Teja patented new ways to prepare glass fibres and roll-out steel sheets, among other things.

All this was before he moved back to India in 1960. “I was tired of making money, and I had a yearning to do something for my country,” he told Mitra with “misty eyes”.

Later, in 1970, Teja would testify in court that he hadn’t lived in India since 1948. Even after he started Jayanti Shipping Company, he would maintain that his primary residence was in France, and he travelled to India “about 40 times a year”.

Also read: Is Modi a better builder of India or Nehru? They aren’t all that different

An international man of mystery

Whether or not Teja was an Indian resident, Nehru thought he could revolutionise shipping in the country. Teja, though, saw himself as somewhere between a diplomat and a socialite. The folklore around him intensified between 1966 and 1971, while Teja and his wife, Ranjit, were living abroad and trying to escape extradition to India.

The couple was well known among elite circles globally, from London to New York. “His wife played a major role in networking — she complemented him, and they fitted in well with Delhi’s influential circles,” Danish Khan said.

Ranjit Teja added to the aura around the man. She was charming and witty and became the talk of the town after she supposedly kissed Nehru’s cheek at a party. Even veteran CPI member Indrajit Gupta, right after insisting in Parliament that he would focus on the facts of Teja’s alleged crimes instead of rumours and gossip, couldn’t help referencing his wife. “…there was also the beauteous Mrs Teja whose face probably like that of Helen of Troy was meant to launch a thousand bulk-carriers,” Gupta said in 1966.

But after Nehru’s death in 1964, Teja was no longer a favourite. His relationship with the new PM Lal Bahadur Shastri and his private secretary Chandrika Prasad Srivastava were strained, and the first investigations against Teja started around this time.

The dominoes began to fall in the summer of 1966, when the Indira Gandhi government directed an official inquiry into Jayanti Shipping’s affairs, and the Shipping Corporation of India, headed by Shastri’s private secretary, took over the management of the company.

Teja knew that people were out to get him. He was frustrated that his reputation preceded him: Future business ventures were being nipped in the bud.

He told Mitra in 1983 that when someone’s reputation takes a hit, all credit dries up. Speaking to ThePrint, Mitra averred that there was always an anti-Nehru group working against Dharma Teja — and that at one point, they named him as part of a plot to kill Lal Bahadur Shastri.

According to this rumour, Teja was in Tashkent when Lal Bahadur Shastri died there on 11 January 1966. Then Minister of External Affairs, Swaran Singh, had to clear up the confusion in Parliament: The Teja present in Tashkent was the Information Secretary of the Indian Embassy there.

Also Read: Hungry India, a nawabi US President, ‘Mexican blood’ — The real story of Green Revolution

The luxurious life of a millionaire fugitive

What was clear by now was that Teja’s spell was broken and even Indira Gandhi as Prime Minister couldn’t protect her family friend. He was now an elite symbol of wealth and privilege in socialist India, and his time was up.

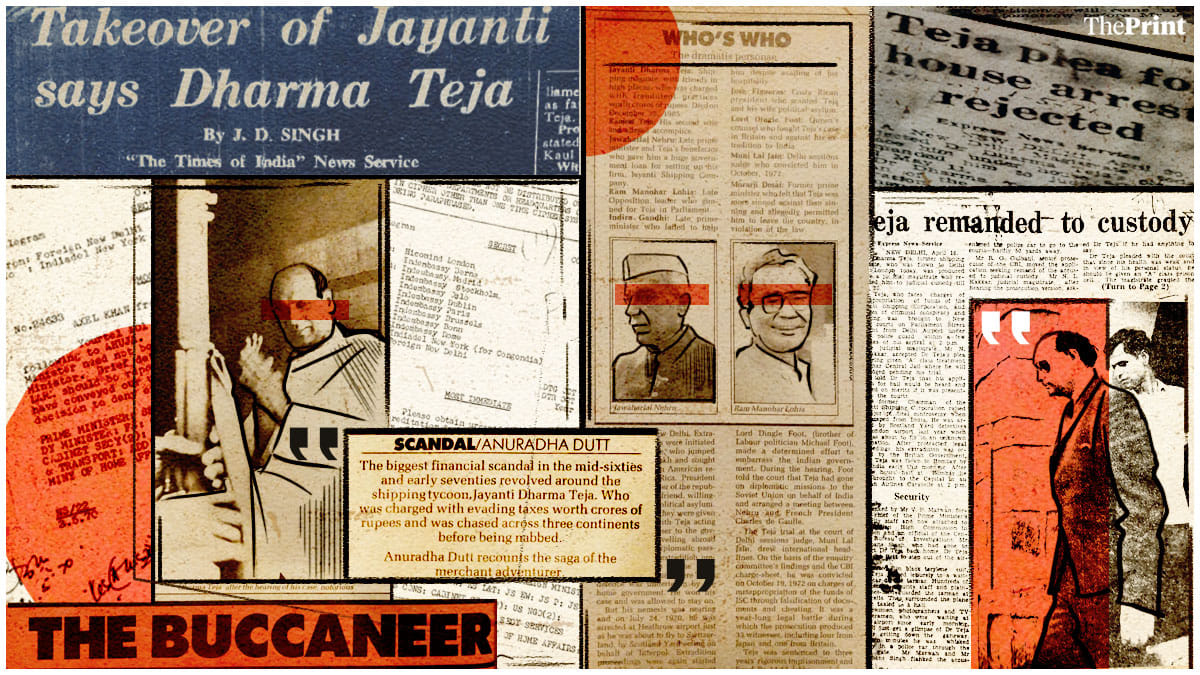

Teja’s name came up in parliamentary debates dozens of times over the years. On 24 August 1966, for instance, the likes of Ram Manohar Lohia, Madhu Limaye, and SM Banerjee excoriated him for hours.

“There is something very wrong with this system which permits our ministers and our Cabinet to become absolutely hypnotised, mesmerised, bewildered and dazzled by the spectacle of these flamboyant figures of the business world,” exclaimed Communist party MP Indrajit Gupta. “Dr Teja was a flamboyant figure. There is no doubt about it.”

As Parliament crucified him, Teja and his wife were holidaying at their Villa Cashmere in the French Riviera.

“I remember he said that it was too much to bear,” Mitra said. “His wife, Ranjit, had also become frazzled. They were at the end of their patience, and so they had to leave India.”

Teja was accused of all sorts of crimes, ranging from financial to immigration fraud. The allegations included large-scale embezzlement, misappropriation of funds, missed payments on vessels, forgery, visa fraud and passport violations.

By the time the Indian authorities located him in France, the couple had set off on a road trip across Europe, leading law enforcement on a wild goose chase for five years. Indian embassies across the world furiously tried to keep track of him.

The couple was next spotted in New York in February 1967, applying for permanent residency — the Indian government had cancelled Teja’s passport in October 1966. The US, however, worked with India’s Consul General to knock back their application, initiate deportation proceedings, and arrest them in April for overstaying their visa. India also obtained warrants for their arrest and extradition.

Ranjit Teja was reportedly instrumental in convincing an American magistrate to grant the couple bail. She told him that they were “victims of political vendetta” due to their prior relations with Nehru and were not the kind to abscond. They were granted bail, and left the United States of America for Costa Rica by that September.

The Tejas’ successful escape to Costa Rica, understood to be a banana republic, hinged on India’s non-existent diplomatic presence there. The couple had also made friends with former Costa Rican President Jose Maria Hipolito Figueres Ferrer and his Foreign Minister.

The Tejas remained in Costa Rica for the next three years, living on cancelled visas and unable to obtain political asylum. In June 1969, the Costa Rican Supreme Court voted against the couple’s extradition, bringing to an end a protracted process that set the Indian public coffers back by Rs 4.9 lakh.

“We presume you have conveyed our unhappiness at Costa Rican government’s decision to deny extradition of Dr. and Mrs. Teja,” the Foreign Ministry said in a May 1970 telegram fired off to the Indian embassy in New York. The embassy in New York tried to assuage the Foreign Ministry in its reply: The positive news was that the Costa Rican government didn’t think Teja was being politically persecuted in India, despite “fiery debates in the Indian Parliament”.

The following year, Ferrer returned to power and issued Teja with a diplomatic passport under the name Jayanti Dharma Konduru, giving him a clean chit to carry on with his globetrotting.

Teja, however, became too confident too soon. He was finally arrested by Scotland Yard at London’s Heathrow Airport in May 1970 for falsifying his identity — he owned up to it, and allegedly bragged about personally receiving the diplomatic passport from President Ferrer.

A secret telegram marked “most immediate” was sent a few months later from the Indian High Commission in London to Indian embassies all across Europe: “Please obtain urgently from Foreign Office of your accreditation list of foreign diplomats… Dr. Teja is not an accredited diplomat in the UK and since he may be holding air ticket to your country he is likely to claim that he was en route to it to charge of a diplomatic assignment when apprehended. Matter extremely urgent.”

Teja’s confidence carried him through the rest of the legal process. Until the very end, he insisted that none of India’s tax demands applied to him because he was a diplomat, a non-resident India, had renounced his Indian citizenship, and had no income accrued in India.

“He flexed his political muscles,” Ruhi Khan said. “He was posturing politically — and eventually, his political opponents pulled him down.”

Also read: A billionaire from nowhere: The over ambitious journey of diamond mogul Nirav Modi

A “successor to Nehru” ?

In return for being hounded, Teja did his best to embarrass the Indian government.

His extradition trial attracted widespread attention in London, and Teja argued in court that he wouldn’t receive a fair trial in India because of the biased media coverage. He told the British court that he jumped bail in New York after consulting his friends — including the Indian ambassador in Washington. He produced letters from Morarji Desai, dated 1969, to back his claims. He said that he had been asked to donate to a newspaper run by Uma Shankar Dikshit, who became treasurer of the Congress party. He informed the court that after Nehru’s death, “young people” like him in India were being targeted.

According to archived news reports, Teja also testified that Nehru entrusted him with top-secret diplomatic missions.

He said that he made 14 trips to Russia during and after the 1962 Indo-China war to seek help. His other “diplomatic activities” included arranging a meeting between Nehru and then French president Charles de Gaulle. He had also “informally taken up the question of an Asian security pact with Japan against China,” he claimed.

When asked in court if there was “talk in India of [him] being successor to Nehru”, Teja declined to comment — it’s unclear if the Nehru in question was the former prime minister, or diplomat and Indian Ambassador to the United States, B.K. Nehru.

“Nehru’s friend claims he is ‘persecuted’,” declared the Daily Telegraph in January 1971. “Takeover of Jayanti a ‘political act’, says Dharma Teja,” ran a Times of India headline in November 1970, printing a detailed breakdown of the trial from London.

Ultimately, Teja lost the extradition case and left the UK on 15 April 1971. After he landed in India, he exited the flight dressed in a “black terylene suit,” and “walked leisurely” to a waiting car. He was then escorted to the police superintendent’s office, where he was served soft drinks, The Indian Express reported on 17 April 1971. He smiled at reporters but made no comment.

The trial in India lasted a year, and he was sentenced to three years of imprisonment and was fined Rs 14.3 lakh. In his bail application in July 1970, Teja reiterated his “close personal relationship” with Nehru but also cited a doctor’s report to claim that he was “suffering from psychosis, angina and narcolepsy” making the detention in Tihar a threat to his life.

While imprisoned at Tihar Jail, Teja continued to host dignitaries, insisting to Mitra that the captivity allowed him to catch up on his reading and writing. He was released in 1975, after which he settled in Hyderabad. His name was added to international airlines’ no-fly lists.

But the story doesn’t end here: Somehow, despite it all, Teja slipped out of the country again in May 1977.

“No one can travel without valid papers, and I was no exception. I had to go back to Europe because my wife and the two younger children were there,” he said when Mitra asked how he managed to leave in 1977. The Indian government said he’d ‘disappeared.’

However, there wasn’t really such a big mystery. Teja had flown to New York from New Delhi on a Pan Am ticket, and was reportedly seen off at the airport by Kanti Desai, then-Prime Minister Morarji Desai’s son, and the sitting industries’ minister Sikander Bakht. The government not only knew he was leaving India, they had dropped him off at the airport.

“Teja is free to come and go whenever he chooses. The country has got more from him than what he owes,” Morarji Desai announced in Parliament in 1978. Clearly, Teja still had some members of Lutyens’ Delhi wrapped around his finger, and the matter was closed.

Teja later told Mitra that he renewed his passport four times after that, between 1977 and 1983, at the Indian embassy in Geneva. “I met many Indian dignitaries in the interim,” he said.

He also wrote research papers on nuclear physics, went skiing on weekends, and swam in the Mediterranean.

The last laugh

The last time Teja returned to India was in 1983.

While he had plans to set up a business, he went off the radar quickly. Mitra presumes he left India for good some time after Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984. He suspects that Teja knew he had no political goodwill left with the Congress’s new guard.

Even as the Morarji Desai government politely turned a blind eye to Teja, the succeeding Charan Singh-led regime filed a lawsuit against American airlines Pan Am for allowing Teja to fly out of the country in 1977. Pan Am, in return, said that Teja was given a farewell by government officials at the airport. Even after Teja returned in 1983, the government continued to hold Pan Am financially liable.

Teja died on Christmas Day in New Jersey in 1985. And while the legal troubles continued, he had the last laugh in death.

In December 1988, Pan Am was asked to pay Teja’s outstanding dues, amounting to over Rs 10 crore. Pan Am went bankrupt in 1991 — ultimately, then it was a defunct foreign organisation that had to cover for Teja. Jayanti Shipping filed a lawsuit against Teja’s estate, claiming financial recovery of Rs 1.3 crore. An order passed in 2010 ruled in favour of Jayanti Shipping, but it’s unclear who is paying up.

With very few people who knew him personally still alive, Teja remains shrouded in mystery, fables, and anecdotes. Of his own thoughts during his life, not much is known, although when he was imprisoned in Tihar Jail, he apparently wrote a volume of poetry, titled Penelope, and two unpublished novels.

A member of Teja’s family, who wished to remain anonymous, said to ThePrint that Teja’s story is often misunderstood and misrepresented by the media.

“His name is always brought up in connection with economic crimes,” they said. “He is a very accomplished person who was misunderstood.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)