Observing the fate of maharajahs whose lands were ‘assumed’ by the British, a senior official would in time remark how ‘the loss of much of their real power’ tended to make Indian princes ‘anxious to preserve forms that yet remain of royalty’. This typically took the form of religious ceremony and acts of piety. Serfoji was no exception: One of his first deeds was to eject British troops garrisoned in the eleventh-century Siva temple in Tanjore, and having ritually purified it, to order renovations.

Tanjore was once the seat of the medieval Chola emperors, and then the Nayaka dynasty linked to Vijayanagara. Serfoji’s Maratha ancestors came here as agents of an enemy sultan to assist the last of the Nayakas in a contest, only to quickly seize the kingdom for themselves.

Awkwardness about this less-than-gallant ascent to power was papered over with poetry: It was claimed that Siva called on the first Maratha rajah in a dream, confirming his right over Tanjore. But another device to craft legitimacy was supporting the temple and its patronage networks…Serfoji, in fact, with power dissolved and his house a shell of what it was, literally inscribed on the walls of the structure a genealogy of the Marathas—a closing signature by a prince who understood he and his kind were fast becoming history. In that sense, he was enacting a ‘traditional’ Hindu expression of kingship, anchored in religion and dynastic glory.

But Serfoji was no tragic soul, seeking consolation in empty ritualism and temple patronage. With the little authority left in him as master of a single fort-city, and the monetary resources the British allotted him, the rajah also inaugurated what has been called the ‘Tanjore Renaissance’ and the ‘Tanjore Enlightenment’. It was, to quote a scholar, ‘a knowledge-making process that combined indigenous wisdom with all that was relevant and useful’ in Western culture; it produced modern knowledge that yet remained ‘rooted in tradition’. That is, the rajah made a mark not as a political being but as an innovative intellectual.

For example, on the one hand, Serfoji founded institutions for Vedic studies, meeting Brahmin ideals of kingly conduct. But on the other, he also established twenty-one schools offering free education of the European kind, albeit ‘disengaged from Christian frames of reference’.

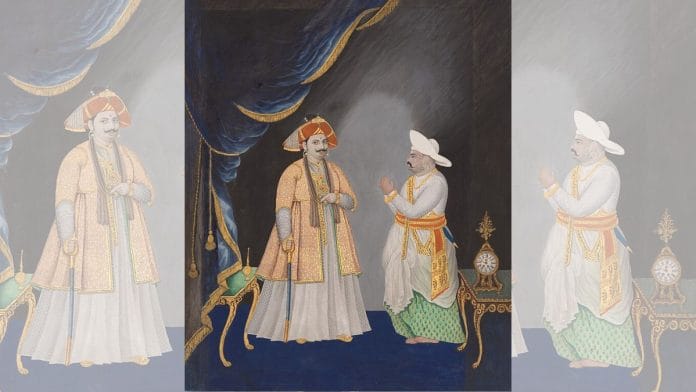

Also read: Exquisite 19th century stolen painting of Maharaja Serfoji II traced to US museum

While years later, there would still be debates within the colonial establishment on whether vernacular or English education ought to receive official backing, Serfoji—a rajah ‘with less power than an English nobleman’—gave students instruction in five languages: Tamil (of the masses), Marathi (of his court), Telugu (a prestigious language from Vijayanagara’s heyday), Persian (favourite of the Mughal order), and, of course, English (from India’s new overlords).

One school, attached to an almshouse named after a beloved consort alone had fifteen teachers and 464 pupils, with a Vedic pathasala (academy) and temple functioning in parallel. All at once, that is, this brown prince helmed a ‘native’ engagement with European modernity—a process, not imposed by the British from above, but pursued with a measure of autonomy.

These innovations were mastered by Serfoji in a period when Company authorities in Madras were hesitant to support public instruction—in setting up schools, the rajah was borrowing, in fact, from Christian missions, many of which separately received his support too. Yet, he was also moulding something new: Instead of using the usual highbrow term sarva-vidya-kalanidhi-salai (‘house for the study of all sciences and arts’), the palace school was called the nava-vidya-kalanidhi-salai (‘house of the study of new learning’), for example.

As with Christian mission institutions—and here perhaps can be traced his mentor Schwartz’s influence—caste rules were relaxed; orphans and disabled children were admitted; and food and board provided to all in need of it. Serfoji was equally conscious that in an impoverished country, knowledge for its own sake would not go far—the idea was to endow students with practical skills in gaining employment in Company offices, including by providing access to languages of power.

Products of the Tanjore system would in time spread across southern India, achieving distinction…Moreover, the rajah personally crafted textbooks, keeping them familiar to pupils in format, while also conveying new ideas absorbed from overseas. In its outer shell, this was Hindu learning, but the yolk inside had a Western flavour. Only an Indian well versed in European and ‘native’ ideas both could pull off something like this; only a Serfoji could Indianize the white man’s knowledge and smoothly blend it with local culture.

An example appears in Serfoji’s adapted kuravanji play format, which, as the scholar Indira Viswanathan Peterson notes, was long popular in Tamil country for its ‘heterogeneous characters, combined with its comic plot’, and a fortune teller as its central figure. The stories typically drew from mythology and folklore, and were consumed by a variety of audiences. In Serfoji’s Devendra Kuravanji, however, there is a difference.

In this Marathi text, the goddess Indrani meets with a fortune teller and asks her to speak of rivers, mountains and the numerous countries of the world. To an extent, all familiar. But then, she demands unusually: ‘Tell me, what is the moon’s orbit, and what planets revolve around the sun? What is the diameter of the Earthsphere?’ For this was a modern geography and astronomy class, and Indrani’s interlocutor elucidates Copernican ideas, weaving a verbal picture of the globe. Besides, as one writer put it, kuravanjis usually featured temple towns: Tirupati, Chidambaram, Benares and Rameswaram.

With Serfoji, however, the listener encounters a new world: Delaware and Edinburgh, North Carolina and Ottawa, Jamaica and Nigeria, New York and Lisbon. Instead of Puranic tales and concepts, the Devendra Kuravanji edified and educated in a new way, transmitting what the rajah had learnt in English to a wider audience in an Indian language.

Indeed, as the fortune teller declares to Indrani, ‘You know the cosmology of the Puranas. Listen! I shall now tell you a cosmography and geography different from that one.’ Both Indrani and her discussant were known to the listeners; it was what they spoke that was novel. Nor did this knowledge seem too intimidating or disruptive. For emerging from the mouths of established characters, they deftly sewed the unfamiliar into the familiar.

While the rajah patronized everything from Sanskrit academies in Benares to missionary work in districts adjoining his seat, the hub of his intellectual pursuits was, of course, Tanjore.

In fact, by the 1820s, there was such demand from every passing European to visit Serfoji’s palace that he was forced to register a complaint about not wanting to make his home a ‘Shew House’. But public curiosity can be forgiven given the sheer activity underway in the fort. To its dispensary, for example, was attached a posse of experts: doctors who specialized in handling poison, eye diseases, urinary disorders and so on, their research and remedies catalogued in Tamil verse. Art supplies and painting material were imported for the court painters, who invented a hybrid Anglo–Indian style and were soon in demand with Company officials.

Most significantly, in a city with a palace and a great temple, Serfoji emphasised a very different type of monument: the Sarasvati Mahal library. Originally under the Nayakas, its expanded shelves now featured 4500 books in Western languages, and ten times as many Indian manuscripts. European music occupied thirty volumes, with local performers trained to play both the Indian veena and the piano.

White residents in and around Tanjore were overawed by the rajah’s literary hoard, delighted when he allowed them to borrow. Even today, a visit takes us into a hall with cupboards stacked on cupboards, many filled with palm-leaf texts in Indian languages. That most of this was the collection of a single productive mind makes the experience only more astonishing. If the rajah believed himself, as a British official grumbled, to be ‘the most interesting object in Hindoostan’, one can forgive his immodesty.

This excerpt from ‘Gods, Guns and Missionaries’ by Manu S Pillai has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘Gods, Guns and Missionaries’ by Manu S Pillai has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.