When Deepak Chopra, who today is internationally recognized as one of the leaders of the integrative approach to medicine, arrived in New Jersey in 1970 fresh out of medical school in India, he got a firsthand introduction to the situation. “When I walked into the ER for my first shift,” he recalled, “the doctors who showed me my locker and gave me a tour of the acute facilities were not Americans.

There was one German, but the rest had Asian faces like mine, from India, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Korea… What had brought so many foreign doctors together was the Vietnam War. A severe doctor shortage had arisen as the army drained away medical graduates while other young men, who might have wanted to become doctors, were drafted to fight.”

War had added an additional layer of stress on the health care system. During the Vietnam War, the shortage of men in the labor force had become a cause for concern. More than 9 million Americans—mostly men—served on active duty between 1961 and 1975.

Medical personnel were needed in the war effort, adding to the shortage of available doctors for civilians. Thanks to advances in medical care on the frontlines, many more soldiers were surviving their injuries. Seventy-five thousand severely disabled veterans returned to the United States, many of whom would need years of continuing care, increasing the pressure on an already overwhelmed health care system.

Europe no longer supplied qualified doctors looking for overseas opportunities; they had plenty of jobs at home. In the forties and fifties, Indians still considered the U.K. as the place to go for higher education, but by the sixties it had lost ground to America. There was a class of research-oriented doctors in India that had reached the limit of the resources that Indian institutions had to offer. They had no choice but to come to the West if they wished to pursue their studies.

Also read: How England came to support a Jewish state in Palestine—‘civilizer of the backward countries’

As Dr. Bibhuthi Mishra, an Indian physician recalled, “I left India after doing a specialization in internal medicine. I wanted to do work in molecular biology in DNA and immunology and although there were a few labs in India, only one was doing advanced work of an international standard and they didn’t take students. The money being spent on biological research in India in 1981 was pitiful. Many of my friends in the field who were gifted were leaving. The first place I went to was London, but there was no comparison to the United States where substantial investments in medicine and biological research were being made ever since Nixon began the Cancer Institute. The U.K. funding was limited unless you were at the top institutions. I was working on a research paper, but a group in the United States overtook me. The lab in the United States was like a palace compared to India. I wanted to pursue the work I was trained to do, so I moved to the United States Today, India has caught up, but in the eighties, there was no choice really.”

The United States had become the number-one destination for Indian graduates in STEM fields, but there were other reasons why America was such an attractive destination. It was a country of immigrants and a more welcoming environment for immigrants from India. Sanjiv Chopra, who rose to become a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, followed his older brother, Deepak to Boston in the seventies.

He observed, “Our father’s generation had gone to England to complete their training, but they had encountered a British ceiling. Indian doctors in England were allowed to rise to only a certain level, and when they returned to India they were behind their classmates in seniority and only rarely caught up… When people asked us what our plans were when we finished medical school, America was the obvious answer.”

Initially, some Indian-trained doctors had gone to the U.K., but the attraction of opportunities in the United States convinced many of them to move.

The most pressing need for doctors in the United States was among its most run-down or underserved populations, who resided primarily in cities or in rural areas like Appalachia. The 1960s saw a precipitous decline in urban areas of its wealthier, white population who were leaving en masse for the suburbs. This left urban areas with a lower tax base and far fewer resources as businesses followed suit and urban decay set in.

The shift to the suburbs had been facilitated by the massive highway-building program undertaken by the government after World War II, which had the ancillary benefit of making it easier for people to commute. The I bill had created opportunities for its white beneficiaries,63 and the relocation of businesses outside of urban centers had extended communities outwards. The migration of African American Southerners to the North that increased during this period combined with desegregation and the race riots in the sixties, contributed to what was called “white flight”—the white population moving out of cities in droves.

Wealthy, well-resourced hospitals moved with their clients to the suburbs, the preferred place for many doctors to practice. It was not easy for a hospital in downtown Newark or Detroit, still burning from the race riots, to attract a well-to-do white graduate of Harvard Medical School to practice there.

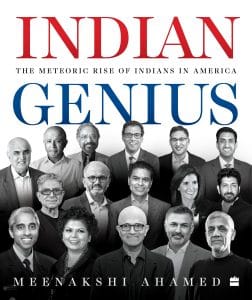

This excerpt from ‘Indian Genius: The Meteoric Rise of Indians in America’ by Meenakshi Ahamed has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from ‘Indian Genius: The Meteoric Rise of Indians in America’ by Meenakshi Ahamed has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

Indian doctors have been flocking to the USA in 1959s and 60s as well.

A stalwart of those years was Dr. Sujoy V Roy, an eminent cardiologist at Harvard Medical School. He was invited by Pandit Nehru to come to India and setup the Department of Cardiology at the newly established AIIMS.