Aparna Sen’s Mr. and Mrs. Iyer was released in 2002, in the aftermath of the carnage in Godhra, Gujarat. The film is a restrained and compassionate account of ordinary individuals caught in the crosshairs of a communal riot that leaves devastation and misery in its wake. However, it was marketed as a love story set amidst communal riots.

Set in an unidentified place in the Himalayan foothills, it revolves around Meenakshi Iyer (played by Konkona Sen Sharma) who is travelling back to Calcutta with her baby son Santhanam. The first part of the journey is by bus, and among her fellow passengers is Raja Chowdhury (played by Rahul Bose), who has been requested by her parents to take care of her during the journey. In the meantime, a riot ensues, sparked off by the killing of a Muslim man and resulting in Muslims burning Hindu villages. A curfew prevents the movement of vehicles and people, and thus Raja and Meenakshi are thrown about together as they find it nearly impossible to continue their journey forward. She identifies him as her husband to save him despite her initial rejection of him as a Muslim man because of her conservative upbringing and caste prejudices. The bond of affection which springs up between the two seems to be Sen’s message to the world at large: that this is the only way forward in a world divided by sectarian politics.

To express her strong views about communalism and the destruction it leaves in its wake, Sen uses the trope of the bus journey which becomes an experience that leaves none of its passengers unscathed. The film begins in a South Indian household where a baby and a mother are getting ready for a journey. Then the narrative moves to a bus stop where Meenakshi Iyer and her son are to board a bus to the plains to catch a train back to Calcutta. It is at this bus stop that she meets Raja Choudhary, the other principal character of Sen’s story. Of the subject matter of Mr. and Mrs. Iyer, Sen said, ‘I wanted to make a love story and I always wanted to make a film about a journey. I really do feel that an external journey is a very meaningful metaphor for an internal one because a journey opens you up to new experiences, you find out things about yourself and about others that you have hitherto not even expected.’

Communal violence has formed the subject matter of many a work in Indian cinema—from the violence unleashed during the Partition in 1947, right up to the Bombay riots in 1992, and finally the Godhra carnage and its aftermath. Since then, this violent episode in the history of modern India has found many a depiction on celluloid—Firaaq (2008) by Nandita Das and Parzania (2007) by Rahul Dholakia being two other films on the same issue. In an interview, Aparna Sen said that the backdrop of her story, however, was the 9/11 attacks.

Where Bollywood prefers an overdoing of emotions, Sen’s film is rather understated and can even be called lyrical. It is about two strangers belonging to two different cultures and religions, who come together during the very brief period of a bus ride, spend two days together, and fall in love with one another. The backdrop to this—the killings—is mostly reported and none of it is allowed to spill over into Mr. and Mrs. Iyer’s love story. There are quieter and more contemplative moments in the story punctuated by killings and reports of violence coming in, but it is these moments which make the film special. Deepa Mehta’s film Earth also reports on the violence which erupted during the Partition when India and Pakistan became two separate nation states; but while it comes across as a more gendered rendition of the same, Sen’s approach is more humanitarian. Her film’s protagonist Mrs Iyer gives up her caste prejudices to save the life of a man who has been nothing but kind and solicitous to her, but who nevertheless remains a stranger. It is only later that she finds out about his interests, worldview, habits, good qualities, and so on.

Also read: Ritwik Ghatak as FTII teacher: This is the only place in the world where people still want me

It is special because of another reason—the depiction of love between an upper-caste Hindu woman and a Muslim man, which is yet another delicate issue and usually not the staple fare of Indian cinema. Mr. and Mrs. Iyer can be labelled as middle cinema which tries to address the ethical issues that surface in the film. The focus is on individual conflicts rather than community issues, and the film is set in a vague area, although Sen said in an interview that it was set in the Himalayan foothills of North Bengal. One can say that in its own specific way, middle cinema can create a space for the recognition of fundamentalism or ethnic violence (issues which can possibly be resolved there)—a space created by the director that can reassess ethical issues and initiate a questioning of the unwritten moral code in contemporary Indian cinema.

The representation of women’s agency has undergone vast changes in recent years, as has the treatment of communalism, yet there continues to be a sensitive area in which subaltern subjectivities—namely, Hindu women and Muslims—exist. Mr. and Mrs. Iyer is interesting because it refuses a neat closure or a clear-cut moral resolution. It appears to ask more questions than it answers, and in doing so, provides a platform for negotiation about how one should deal with extreme situations—in the narrative, Cohen, one of the passengers in the bus, in order to protect himself from the rioters, tells on an old Muslim couple who are then hauled off the bus and murdered.

The Partition remains a raw wound in the background of all films about India’s multicultural make-up, with the representation of Muslims falling into two neat categories: one, as violent, bloodthirsty fanatics, and second, as sanitized, domesticated and patriotic middle-class liberals. Nevertheless, as in all Aparna Sen films, the Woman question becomes an overwhelming one—here, the upper-caste Hindu Brahmin woman overcomes her scruples and saves the life of one of her fellow Muslim passengers during an attack by Hindu rioters, while Raja, alongside the other men in the bus, fail to react as the elderly Muslim couple are being led away for slaughter. Only a young girl in the bus, who had hitherto mostly been seen to enjoy herself with her other friends, plucks up enough courage to protest.

In the course of the narrative, Raja and Meenakshi are forced to spend a night or two together in a wayside forest bungalow until they are able to catch a train back to the metropolis. This enforced intimacy compels them to engage with questions that involve each other’s cultural milieu. Sen seems to be suggesting that her world is a closed but protected one. Her father usually travels with her to the city in the plains to put her on the train to Calcutta whenever she visits her parents in the hills. Even for this journey, her father requests Raja to take care of his daughter while Meenakshi appears slightly embarrassed about it. It seems that she has not been given space to think about things on her own, and her existence may even be a dull and humdrum one but she doesn’t seem to mind it very much, even accepting it as it is. However, not until much later does she get to appreciate a different sort of lifestyle. While talking to Raja, she begins to understand lives lived differently from her own, hinting at some other kind of existence. Initially, Raja tries to draw Meenakshi into a debate that involves the irrationality of the caste system, but she refuses to enter the argument. Yet later, she changes herself.

Raja is a liberal who represents modern India while Meenakshi is someone who does not question traditional ideas of impurity and caste. Earlier, while they were engaged in play-acting as husband and wife, a gaggle of girls from the bus confronted them and demanded to know their love story. It was only when Raja started to weave the story that Meenakshi got to know him better. His stories about living in the middle of a forest in Wayanad, having

dinner in a tree-house by the light of clay lamps, thrilled her beyond words.

However, Sen seems to be suggesting that despite having an MSc in physics, Meenakshi is still caught up in archaic, myopic customs and beliefs. However, Raja’s conduct with her endears him to her and the two develop a friendship in which she begins to see him as another human being, rather than just a Muslim. She begins enjoying his company and even drinks water from his bottle, while earlier she felt defiled drinking from the same bottle. She begins enjoying little moments of intimacy—as much as a make-believe family of baby, mother and father can.

Through this episode, Sen seems to be suggesting a link between secular education and sociopolitical harmony forged through everyday interactions as the only way one can bring about some kind of enlightened tolerance. Meenakshi not only develops that, but also comes to know about the amount of unbridled courage she has by saving another person’s life. Her conservative outlook is flung aside at the hint of danger that threatens the very lives of the passengers in the bus. Meenakshi decides then and there that she has seen enough meaningless violence in the name of religion to let the Hindu fanatics lead another innocent to the slaughter. She pushes Santhanam into Raja’s lap so that he is rendered speechless, only to follow her lead to act as her make-believe husband in front of the rioters.

Also read: Assamese cinema was born in a tea garden. 1935 film ‘Jaimati’ was the first

The Journey

The motif of the bus journey is symbolic of Meenakshi’s inner journey as a person and she finds herself changed over its course. At the beginning of the journey, she is simply Mrs Iyer from a conservative and orthodox Tamil Brahmin family, who only partakes of vegetarian food and has set notions about the world at large. As the bus makes its way down to the plains below, she finds it more and more difficult to handle her young son on her own, who appears excitable and begins to cry. This irritates most of her other co- passengers until she turns to Raja for assistance; he helps her untiringly.

The scenes in the bus are revealing in the sense that they help delineate the passengers’ characters. The bus consists of a motley crowd of predominantly Hindu Indians, except for a lone Jew and an elderly Muslim couple. The passengers represent a wide range of age, social, linguistic and religious differences. Among them are a group of young college students, a newly wedded couple, a middle-aged woman with a differently abled son, two Sikh men—one elderly, the other slightly younger, a group of Bengali men, and the protagonists, Meenakshi Iyer and Raja Choudhury.

The young college students seem carefree, given to singing and enjoying themselves, as is the wont of youth. At the back of the bus, the Bengali men play cards to while away their time. To the consternation of the woman with the disabled son, they also drink alcohol which the son, unable to understand, wishes to partake of.

In other words, the bus is a microcosm of India. The irritability expressed by many while adjusting to their co-passengers’ presence and needs is an incredibly mimetic reflection of Indian society.

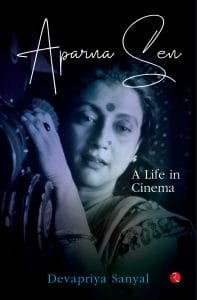

This excerpt from Devapriya Sanyal’s ‘Aparna Sen: A Life in Cinema’ has been published with permission from Rupa Publications India.

This excerpt from Devapriya Sanyal’s ‘Aparna Sen: A Life in Cinema’ has been published with permission from Rupa Publications India.