The interior design of Manik Bagh cost $4 million (about $70 million in today’s terms). In 1932, a convoy of three Hansa Line ships was commissioned to transport orders from Hamburg to India, including prefabricated construction parts and glass and metal bedside lamps. Before the parts’ departure, Muthesius organized an exhibition in Berlin from 3 to 10 January 1932, captured in Emil Leitner’s photographs. Three thousand visitors flocked to admire the models, plans, furniture, and objets d’art bound for Manik Bagh. It was a real triumph!

The public discovered a new style, later dubbed the ‘International Style’ in the following year’s Modern Architecture exhibition, organized by architects HenryRussell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The unique pieces or the limited series which were on their way to India were stuff of dreams to the viewers, and their destination—a maharaja’s palace in the Indies—was stuff of fairy tales. Visitors were struck by the originality of the project, a distillation of the technical spirit of the Bauhaus.

Some twenty carefully selected designers were solicited, whose creations would become iconic works of this period: Marcel Breuer, Ivan da Silva-Bruhns, Djo-Bourgeois, Desny and Clément Nauny, D.I.M., Michel Dufet, Eileen Gray, Hélène Henry, René Herbst, René Lalique, Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand, Hans and Wassili Luckhardt, Eckart Muthesius, Jean Perzel, Jean Puiforcat, Lilly Reich, Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann, Louis Sognot, and Charlotte Alix. All these names were already well known at the time. The maharaja was not a talent scout. On the contrary, he made them known on the international scene.

Bringing these artists to India was a revelation, marking a turning point in Indian architectural history. In 1934, Muthesius organized an exhibition of the modern, modestly-sized palace in Bombay, which proved to be an invaluable revelation for the art scene. It served to illustrate the spread of modern architecture and design beyond Europe. Marcel Breuer’s steel furniture, perfectly suited to the tropical climate, created a sensation. The architect and designer Eileen Gray was a particular favourite of Muthesius and Yeshwant’s, yet, only one object from her—the Transat—took up residence at Manik Bagh.

Other objects, such as the satellite suspension found in the Irish designer’s Paris apartment, were ordered but never delivered. Eileen Gray was a very busy woman at the time: she completed her villa E-1027 in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin in the Alpes-Maritimes, closed her gallery on Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré in Paris in 1930 to become more involved with the UAM.

Also read: Indore Maharaja’s Art Deco palace broke many royal rules. Delhi exhibition shows how

Once completed, the palace was the subject of numerous illustrated reports in magazines such as The Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (1933), The Illustrated Times of India (1934), and Fortune (1934). Jean-Michel Frank, renowned for his simplicity and rejection of superfluous details, was notably absent from this project. Was it because he did not belong to the same circles as the UAM, to which the maharaja was connected, and did not exhibit at the international exhibitions so prized by His Highness?

Only four artists were approached: Bernard Boutet de Monvel, Constantin Brancusi, Jean Lurçat, and Gustave Miklos. What about Giacometti? Too rugged. Picasso? Too bohemian. And the Cubists? There was an intriguing lack of paintings hanging on walls. Several explanations are suggested for their absence: conservation difficulties due to climate, unfulfilled ambitions envisioned by the newlyweds due to the maharani’s untimely death, and the abrupt halt of other ongoing projects.; or simply because it was fashionable to have nothing on the walls, like at the hotel in Noailles, the Hôtel Bischoffsheim, on Place des place des États-Unis, sublimely decorated by Jean-Michel Frank in 1929 (today, it is the Baccarat museum); the architect’s desire to celebrate architecture, with objects having a function in the building, without considering paintings as part of the palace project.

Muthesius was more a modernist architect than a purist modernist. He put cubist pieces on the floor. The floors were covered with carpets, all custom-made by Ivan da SilvaBruhns in his Savigny-sur-Orge factory; they were unique pieces that resembled colourful abstract paintings with architectural compositions. A clever way of compensating for the non-existent paintings on the wall. These creations were designed to fit in with the colour scheme of the palace rooms. The hues of the large carpets with their geometric embellishments matched those of the walls, coated with special paints in varieties of blue, silver, gold and ochre, all created by Ernst Messerschmidt.

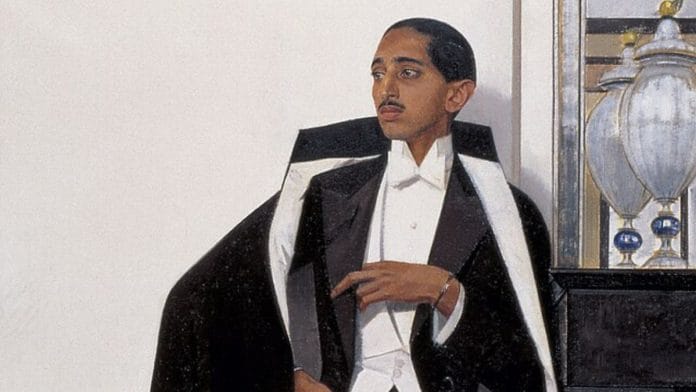

The walls themselves were a work of art. The palace’s artistic touch was evident in the materials used for the walls and the various finishes that created their texture and colour. Could it be that the avantgarde painting, aesthetically crude, simply held no appeal to the maharaja, who was more attracted by sophistication? A sophistication, a chic, a perfectionism, a refinement as glimpsed in Monvel’s portrait of him?

Following the departure of the pieces to India, the geographical distance regrettably led to the palace being forgotten for decades. The palace was rediscovered in September 1970, thanks to a report with colour photographs by Robert Descharnes published in Connaissance des arts, no. 223: En Inde un palais 1930. However, it was just a little too early, because the art world was in a period of upheaval and at the very beginning of the Art Deco period. The modernism of the palace was ahead of time. It was still too early for it to be fully grasped.

This excerpt from ‘The Last Maharaja of Indore: Yeshwant Rao Holkar II – Aesthete, Patron, Tragic Prince’ by Geraldine Lenain, translated by Sindhuja Veeraragavan, has been published with permission from ROLI.

This excerpt from ‘The Last Maharaja of Indore: Yeshwant Rao Holkar II – Aesthete, Patron, Tragic Prince’ by Geraldine Lenain, translated by Sindhuja Veeraragavan, has been published with permission from ROLI.