Usually, Siddhartha had a second vehicle escort his car when he travelled long distances. It was a precaution to ensure that, in case of a vehicle breakdown, his plans didn’t go awry. On that fateful day of 29 July 2019, however, he had chosen to take just the Toyota Innova with the registration number filed in the FIR. Basavaraj Patil, though employed by his company, was not his regular driver. Ravi, who usually drove Siddhartha, was on leave.

When Siddhartha had started from home that afternoon, he had indicated that he would probably visit one of his coffee estates – either in Sakleshpura or Mudigere, both in the Chikkamagaluru district. However, even before reaching Sakleshpura, he had asked the driver to head towards Mangaluru. He had indicated that he was heading for the SEZ but then asked the driver to stop at the bridge over the Netravati river.

On the evening of 29 July, when Patil raised the alarm, Siddhartha’s wife, Malavika, and his elder son, Amartya, were at home in Bengaluru. His younger son, Ishaan, was in Mysuru, at the Gopala Gowda Shanthaveri Memorial Hospital. He was tending to Siddhartha’s father, Gangaiah Hegde, who had slipped into a coma following a fall at his home a few days earlier. Siddhartha’s mother, Vasanthi Hegde, had left the hospital earlier to go back to the Chetanahalli coffee estate – the family seat and ancestral estate – in Chikkamagaluru.

Despite the magnitude of the shock, Malavika and Amartya did not lose their composure. Given the family’s business standing and political connections, phone calls to several of Bengaluru’s ministers, police officers and senior officials were made, informing them of Siddhartha’s disappearance and seeking help.

As the possibility of Siddhartha having jumped to his death became stronger, a formal investigation was launched to trace the missing founder of one of India’s best-known homegrown brands: Café Coffee Day, popularly called CCD.

While the FIR was filed in the early hours of 30 July according to police records, search operations had begun immediately after Patil had made the call to the family.

Also read: Shah Rukh Khan said to Vir Das: ‘Show me what you’ve got’

The Bengaluru administration, well-aware that Siddhartha was one of Karnataka’s best-known entrepreneurs with deep political connections, had swung into action. S. Sasikanth Senthil, who was then the deputy commissioner of the Dakshina Kannada district, recalled that around 6 or 7 p.m., he had received information from the control room that somebody had jumped into the Netravati. Later, they suspected that the person could have been Siddhartha.

Senthil said that he rushed to the spot immediately along with the superintendent of police and the commissioner of police. ‘By that time, the local people were already engaged with the police in the search,’ he remembered.

According to Senthil, the commissioner himself questioned Patil. Siddhartha, according to Patil, had got down from the vehicle and said that he would take a walk, after which he had headed down the bridge while talking on the phone. Patil could not recall anything Siddhartha had said on the phone. He did not see Siddhartha, or anyone else, jump into the river. A local fisherman on the other side of the bridge claimed to have seen someone jump and rushed to the bridge to raise an alarm.3 Patil, immediately realizing that it could be Siddhartha, had started calling the latter’s phone. When he found it switched off, he had called the family and the police.

‘And that’s how we got the information,’ said Senthil.

The timeline of Siddhartha’s disappearance and likely death is riddled with discrepancies. According to the FIR, Patil had started calling Siddhartha’s mobile phone around 8 p.m. When the calls went unanswered, he had called Amartya around 9 p.m.

It was obvious that the police had already received information about the tycoon going missing between 6 and 7 p.m., after which the search had begun in earnest. Of course, given that the FIR was recorded only after midnight, Patil’s recollection of the timeline was not accurate. Even Senthil could not pinpoint when he received the information, though the search had been initiated at least a couple of hours before the time Patil had indicated in the FIR.

What is clear though, is that the police and the administration had acted swiftly and launched a massive search operation involving multiple agencies to find Siddhartha’s body. The men searching for him were under no illusions; they did not expect to find him alive. Firefighters were called in early and had started their search on Monday night, 29 July. The district administration also sought help from naval divers stationed in Karwar, which was about 270 kms from Mangaluru, as well as other diving experts.

When the sun rose on Tuesday, 30 July, the body had still not been spotted. Because of the monsoon, the river was in spate and the search area was huge.

Senthil said that the civil administration sought the help of the Director General (DG) of the Indian Coast Guard, who sent a sonar-equipped hovercraft and a helicopter to aid the search. The National Disaster Rescue Force (NDRF), which specializes in rescue operations during calamities like floods and earthquakes, had also been pressed into service. Despite the coordinated action of multiple search parties, no trace of Siddhartha was found the entire day.

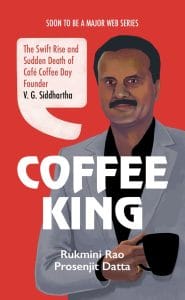

This excerpt from ‘Coffee King’ by Rukmini Rao and Prosenjit Datta has been published with permission from Macmillan.

This excerpt from ‘Coffee King’ by Rukmini Rao and Prosenjit Datta has been published with permission from Macmillan.