For the longest time in my life, I avoided the camera as if it were out to get me. It wasn’t really shyness. I just didn’t see myself as someone made for the lens. I didn’t know my angles, didn’t obsess over my ‘best side,’ and frankly, I didn’t care to. My world was more tactile—art, design, ideas—not selfies and screen time.

I remember a chance encounter with the legendary film-maker Yash Chopra ji at a friend’s dinner. I must have been all of twenty-one at the time. I entered the venue wearing my favourite attire, a saree. He looked at me warmly and said, ‘You are the quintessential Yash Raj film heroine, you should act.’ It was such a generous compliment. I remember being really touched and thanking him with all my heart. But I also told him honestly, ‘I am far too camera-conscious.’ And I truly was. The very idea of performing for a lens made me uneasy. It just never felt like my space.

Up until 2018, if you had shoved a camera in my face, I would have looked like a deer caught in headlights— stiff, silently praying it would all just go away. I even went to absurd lengths to avoid the camera. If a magazine happened to take my photo, I would sometimes call and request that they not use it. That is how uncomfortable I was with being seen.

Part of it, I think, was aesthetic discomfort. I didn’t like how the camera caught me. I felt it was too intense, too sharp. I always felt there was no softness in the gaze, no nuance. It felt jarring, as if I were being misrepresented by the image.

That unease, I realize now, went back further than I thought. Even in school, I had no real interest in either being in front of or even behind the camera. I gravitated towards everything else—painting, craft, sculpture, clay modelling, dance, art, debate. But photography never called to me. I still remember walking past the darkroom and being immediately put off by the smell of developing rolls. There was a sharp, chemical odour that lingered, and with it, my disinterest. While most of my peers associated the camera with magic or memory, it just wasn’t my thing.

Also read: Anthony Hopkins only read 15 pages of The Silence of the Lambs script. ‘Best part I’ve ever read’

Looking back, there was an even deeper reason why I didn’t want to face the camera. In hindsight, I see it may have been a quiet rebellion. For years, I dressed conservatively, keeping myself fully covered because I didn’t like people commenting on my ‘porcelain skin’ or viewing me only through the lens of appearance. I wanted to be taken seriously for my convictions, for my creative work, for the causes I championed, not for these surface-level impressions. Maybe that is why stepping into the camera’s gaze felt so radical.

But somewhere along the way, the world had begun to change. Interviews were shifting from print to video. Visual media was becoming the dominant language. And at the same time, something inside me was shifting too.

In February 2018, I shaved my head during a visit to Tirupati Balaji. It was an act of spiritual reset, though not the first time I had done it. In the past, however, whenever I shaved my head, I would make it a point to retreat from the world for two or three months. I would slow everything down and immerse myself in silence and introspection. This time was different. The India Art Fair was the very next day. International guests were arriving. There was no way I could skip the opening dinner.

My options were limited. I didn’t want to wear a headscarf—that would, in all probability, lead most people to assume that I was unwell. So I did what any slightly dramatic but enterprising woman might do—I ordered a wig. This one was from France. Très chic, you might say . . . only, they sent me a blonde wig. I had no option but to walk into the art fair wearing it, hoping I didn’t attract more attention than the installations. People did doubletakes. ‘Blonde? Really?’ they muttered in surprise. I simply let them wonder.

In my mind, what mattered was that I had shown up. We took hundreds of photos that night, and when I saw them later, I surprised myself. My face looked alive in them. I had stepped into the moment—wig, spotlight and all—and come to think of it, nothing had crumbled.

I think that night I crossed a significant threshold. For once, I hadn’t flinched at my own image. For the first time, I wasn’t shrinking from the spotlight, I was stepping into it. I also came to a quiet realization: this body, this presence, was given to me by God. I asked myself—why had I been hiding it? If a little glamour could help amplify the work I cared about—whether in art, philanthropy, or in reaching a wider audience, there was nothing wrong. I was now certain that I didn’t need to disown beauty in order to be taken seriously. I could claim both, the substance and the shimmer.

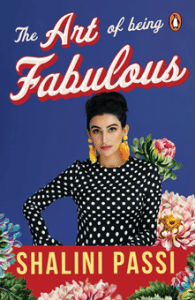

This excerpt from ‘The Art of Being Fabulous’ by Shalini Passi has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘The Art of Being Fabulous’ by Shalini Passi has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.