When the provisional committee met the viceroy, Lord Curzon, in 1899 to brief him about their project, they received a frosty response bordering on the negative. Curzon acknowledged Jamsetji Tata’s generosity but wondered whether there would be enough students to justify the appointment of highly paid professors.

He also expressed doubts as to whether the graduating students would be able to find appropriate jobs in the country. In addition, he did not think it would be right for the government to encourage princely states to contribute to such a project.

Jamsetji Tata sat quietly through this important meeting. If he was deeply disappointed, he did not show it. On the other hand, after the meeting, he told the members of the committee that there was no reason to be discouraged, even though some of them felt the Viceroy had thrown cold water on the scheme. He added that since Curzon was new to the country, perhaps he did not like to commit himself so early.

Most importantly, despite this apparent setback, Jamsetji kept his faith in the project because he believed fervently in the cause. He arranged for distribution of the committee’s project report to educational experts throughout India, for their suggestions and critical comments.

Broadly, the response of these experts was positive, albeit with some critical observations. He also kept alive the negotiations with the government, navigating some difficult conversations and offering to make any minor changes as required by the authorities. Simultaneously, he continued to work on seeking funds for the project.

On this last aspect, he met with success when the dewan of the princely state of Mysore, Sir Seshadri Iyer, whom Jamsetji knew from past interactions, suggested that Bangalore could be considered as the location for the university. He also conveyed a princely offer from the Maharaja of Mysore, who was keen to bring development to his kingdom through higher education.

The Maharaja would provide 375 acres of land in Bangalore, a one-time grant of Rs 5 lakh towards construction of the institute as well as an annual subsidy towards its running. Soon thereafter, a similar competing offer also came from Mumbai, from Chabildas Lalloobhoy, one of the largest landowners in the city.

Also read: ‘Strategic realism’ with ‘economic pragmatism’ — a former diplomat on ‘creative’ economic diplomacy

In the meanwhile, the British government of India suggested that the entire project be examined once again by a well-known scientist. Jamsetji agreed readily, and the provisional committee he had formed finalized the name of Professor William Ramsay, the famous chemist who later also won the Nobel Prize.

Jamsetji agreed to bear all the expenses of Ramsay’s visit and also to pay him a generous fee for the exercise. Ramsay visited India, spending over two months in the country and submitting his report. He too recommended Bangalore as the location for the institute and also provided his views on the initial departments and the staffing that could be considered.

Ramsay also rejected the term ‘university’ for the institute because it did not cover all branches of knowledge. Jamsetji Tata, whose dream had been to create a university, saw the logic of Ramsay’s recommendation, and the name finally accepted for the establishment was ‘Indian Institute of Science’.

The battle had still not been won because the government of India, led by Lord Curzon, had rejected many of Ramsay’s recommendations. Curzon thought that Ramsay’s plan was too lavish, and in 1901 he appointed his own committee to re-examine the entire matter. This committee recommended a smaller institute of study and suggested Roorkee as the location.

Curzon was also unwilling to provide the required financial support from the government, as recommended by Ramsay. It appeared that the government was dragging its feet on the project, and the new proposal of a smaller institute was, in any case, not in line with Jamsetji’s vision of creating a world-class university for India.

Jamsetji Tata was made of sterner stuff. He now took his arguments to London. The year was 1902, and the authorities in London were preoccupied for several weeks with the coronation of King Edward VII.

Jamsetji waited patiently until these festivities had concluded. He then met Lord George Hamilton, Secretary of State for India, and pressed the case for the institute once again. We do not know what exactly transpired at this meeting, but it is clear that soon afterwards, pressure from the India Office in London galvanized the government of India into action.

The government of India announced in May 1903 that they were prepared to make a contribution of £2,000 per year towards the institute, adding to the contributions of Jamsetji and the Maharaja of Mysore. In addition, the government also suggested a flexible method for completion of the required formalities for starting the institute. Suddenly there was light at the end of the tunnel, and it appeared that Jamsetji’s dream would, after all these years, finally come true.

Unfortunately, Jamsetji Tata passed away the next year. However, a few months before his death, he wrote a codicil to his will re-emphasizing his financial commitment to the institute and binding his estate to carry out this undertaking once the institute received full sanction from the government.

It was then left to his elder son, Dorabji Tata, to take forward the final leg of discussions with Lord Curzon and the government of India. Later that year, the government accepted Sir William Ramsay’s recommendations on the size, scale and location of the institute.

It also agreed to make the required financial contribution as well. Within two years, staff were appointed, and in 1909 the vesting orders were issued. In 1911, the first students were admitted to the institute, in the departments of chemistry and electro-technology.

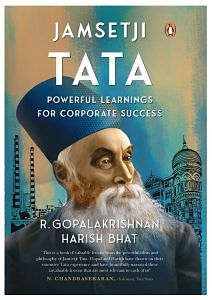

This excerpt from R Gopalakrishnan and Harish Bhat’s book, ‘Jamsetji Tata: Powerful Learnings for Corporate Success’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.