At Roxbury, they had not been idle. Edwin M. Chaffee, one of the founders of Roxbury India Rubber Company, had built a $30,000 machine he called ‘The Monster’ that pummelled, shredded, pounded, heated and rolled the rubber until it submissively formed smooth sheets without having to first dissolve it in turpentine. Since distilling turpentine from pine resin was costly, their savings from not having to use the solvent was the key to their solvency!

Goodyear requested several thousand yards of rubber for his tests but Roxbury demanded payment, which Ely was asked to supply. Goodyear still was not done. He asked for experiments with pigments to be conducted. He appropriated the work of two workers, L.S. Maring and John Nash, both of whom had made small improvements to rubber, promising them payments from the vast amounts of money that would flow in eventually. He hatched plans to buy the Roxbury factory. His disquieting presence was such that, eventually, he was asked to leave Roxbury.

The manager, Samuel Armstrong, was quoted as having said, ‘Goodyear will get tired of building castles in the air after a while.’ Not so. Goodyear continued to place orders with Roxbury for rubber sheets. And he was soon to meet Nathaniel Hayward, who would catalyse Goodyear’s successful rubber vulcanisation quest.

In 1937, fellow American Nathaniel Hayward was twentynine years old and had been with the Eagle India Rubber Company in Woburn, Massachusetts, since 1834. He was the opposite of Goodyear. Where Goodyear was educated, Hayward was illiterate; where Goodyear was humoured as a crank, Hayward was a solid businessman. But both shared the rubber passion.

In 1934, Hayward had heard of rubber and resolved to solve its problems. The story goes that he had a dream one night of rubber, sulphur and lampblack being ‘all that were necessary to make India Rubber’. It didn’t work. So he made a witches’ brew of all the chemicals he had collected and threw rubber into it. It worked! The rubber that emerged was so promising he was offered an immediate position with the Eagle India Rubber Company.

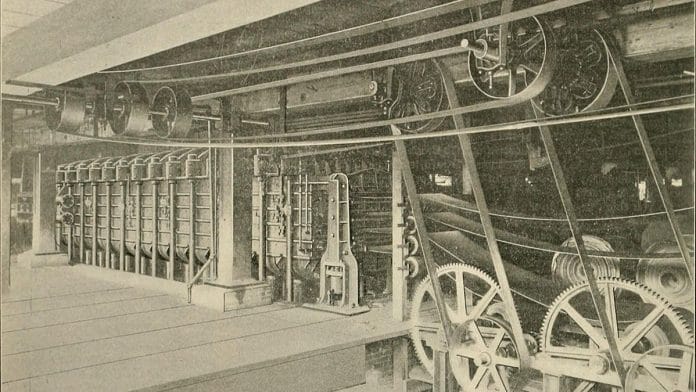

Nathaniel Hayward had spent the previous three years developing his process using sulphur. He discovered that sulphur and exposure to sun caused rubber to ‘set’ into a reliable and stable material. His process was not patented—Hayward was not literate enough to negotiate the process of patenting or the litigation that might follow. Although he had bought out the Eagle India Rubber Company, an economic recession had depressed orders. So Nathaniel and Martin, his brother, made and sold machinery to Roxbury India Rubber Company instead, including a machine with heated rollers and a spreading knife to produce perfectly flat sheets of rubber, which may have been the inspiration for Chaffee’s ‘Monster’.

Roxbury India Rubber Company had reached out to Hayward’s Eagle India Company to request some of his high-quality sheets of rubber to fulfil Goodyear’s orders. Fearful of his sulphur process being discovered—Goodyear’s reputation for opportunism had preceded him—Hayward omitted sulphur from the rubber processing. The sheets were not satisfactory. So Hayward again applied his sulphuring process, and the improved sheets made their way to Goodyear, who approved them. He also caught the scent of brimstone.

Also read: Why the Korean War was a defining moment for India’s foreign policy

Intrigued, Goodyear travelled up to Woburn to see the plant, but Hayward would not allow him inside. In frustration, Goodyear confronted him—if he used sulphur, to say so, or he would apply for a patent for the use of sulphur on rubber. Cornered, Hayward confessed his illiteracy and his use of sulphur.

Goodyear became charming. He persuaded Hayward to sell him the Eagle India Rubber Company and then employed Hayward for $800 a year, with the understanding that Hayward’s employment was contingent on orders coming in. He offered to file a patent in Hayward’s name and be named as the assignor, which Hayward gratefully agreed to. The US patent 1,090A was applied for on 23 November 1938 and granted on 24 February 1839: ‘Improvement in the mode of preparing caoutchouc with sulfur for the manufacture of various articles.’

They worked together to optimise Hayward’s sulphur-and-solarisation procedure and Goodyear’s acid gas treatment, and were awarded a contract for mailbags from the United States Postal Service (USPS). The Boston Post trumpeted Goodyear’s wonderful product. Hayward was not mentioned, and his name is still absent from historical websites paying homage to rubber manufacturing in Woburn.

Goodyear cheerfully promoted the bags they had made for the USPS, colourised with pigments to make them attractive. He took his family on vacation, secure in the feeling that he had turned the corner at last. They returned to find the bags had decomposed; the handles had not even been strong enough to hold up the weight of the bags when empty. Perhaps the problem lay with the colouring agents, which had not been tested in the process. In any case, it was a disaster.

Despite being unable to fulfil the postal order, Goodyear and Hayward continued to manufacture other rubber materials, but Goodyear’s obsession slowly became a millstone around his family’s neck. His parents and Clarissa demanded he throw in the towel and return to hardware. His silent partner, William Ely, was almost destitute. One day, as Ely sat in a small room heated with a single stove, Samuel Armstrong (the manager of the Roxbury India Rubber Company) approached him to request overdue payment, but Ely told him to come back later.

Ely claimed that, at the time, he had been holding a piece of Goodyear’s rubber and had tossed it angrily towards the stove. Armstrong left, and returned to find Ely holding the piece of charred rubber. It had been transformed into a blackened leathery material, sturdy but flexible. A Goodyear biographer, Richard Korman, reports Armstrong to have later said ‘Ely appeared a good deal excited at the time, and thought it was a new feature in India rubber.’ Ely showed the piece to Goodyear a few days later, and Goodyear professed his surprise at this transformation of the rubber. He began searing pieces of treated rubber. But, as Goodyear later told the story, it was he who had made the discovery one night when he had touched a piece of rubber to a hot stove.

Goodyear became obsessive. He experimented endlessly, trying to char the rubber just so. He went to the Woburn factory, but it took him time, effort and money to test the exact method of heating. Heating too quickly at too high a temperature caused the rubber to burn with a ghastly effulgence; to cook it too slow meant it failed to achieve the right temperament.

Again, he used every cent he could lay his hands on, including pawning his children’s schoolbooks, not paying his creditors and making his family scrounge for food and wood for heating. His elderly parents were in tears. ‘Once, we were rich,’ Amasa said to a neighbour. Goodyear was hauled off to debtor’s prison again and again. He was beset on all sides: Ely was demanding rubber goods to sell in his store as part of their long-time agreement; Hayward was not promptly and efficiently fulfilling orders according to their agreement; Clarissa was pregnant again; Goodyear was destitute again; and his child, three-year-old William Henry—the second little boy they had named William Henry—died.

Frustrated by Charles’ fantasies, his brother Amasa Jr. and his father Amasa decided to restore their own dissipated fortune by importing pineapples from Florida, and so moved there. But within a short time, they all sickened with yellow fever and died. This prostrated Goodyear for a short time, but he took it as a sign to persevere. Charles’s mother moved away to live with her son Robert in Connecticut. Goodyear scrounged a little money from friends and acquaintances, and sold a certain Horace Cutler on his ideas but could not deliver on them, which severed the relationship. Goodyear ended back in debtor’s prison.

In 1842, he sent a sulphur-treated sample with Stephen Moulton to Britain, where he hoped that he would have better luck than in the US, and better luck than with the acid-cured sample he had sent previously to Britain with his doctor, Thomas Bradshaw. Moulton, who was young and quite unsuited to business intrigue, showed the samples to Charles Macintosh, Thomas Hancock’s business partner.

Although impressed with the quality, Macintosh told Moulton that Goodyear should patent the process and then come in person to talk about licensing. Moulton acquiesced, but left the samples with Macintosh on the condition that they were not used ‘to the prejudice of Mr. Goodyear’. Independently, Goodyear himself finally came to the decision that he must patent his sulphur treatment process if he was to reap any benefit.

On 15 June 1844, Goodyear was awarded US patent 3,633 ‘Improvement in India-Rubber Fabrics’.

This excerpt from Vidya Rajan’s ‘Rubber’ has been published with permission from Westland Books.

This excerpt from Vidya Rajan’s ‘Rubber’ has been published with permission from Westland Books.