Three years after Shah Nawaz Khan’s report placed a firm lid on the legends of Subhas Chandra Bose’s survival, they erupted again in a way so unusual that to say ‘Who could have thought of it?’ would be an understatement.

Think of it as a movie shot playing on your mobile: The camera pans in a green verdant part of the country—the Falakata region in the Cooch Behar district of West Bengal. It zooms in on a sadhu knocking at the door of an old-fashioned house. One Ramani Ranjan Das, a general medical practitioner, comes forth. He has a lump in his throat as he realizes that the sadhu was someone he had known years ago.

Your exasperation that you couldn’t care less about a sadhu meeting whoever might dwindle when we tell you that we’ve just dramatized what we read in an intelligence report. Those of you in Bengal might think back to the Bhawal Sannyasi case. One day in 1920, a holy man covered in vibhuti (sacred ash) showed up and announced that he was the erstwhile zamindar of the Bhawal estate, who was presumed dead a decade earlier. The zamindar’s widow refuted the claim, while his sister accepted it. There was a two-decade long court drama like nothing in India that went right up to the Privy Council in London, intriguing everyone in Bengal, including Bose. The case settled in the favour of the holy man but he died soon after the verdict.

There were flashes of the Bhawal Sannyasi case with regards to the sadhu who showed up at Ramani Ranjan Das’s home in 1959. The Bhawal Sannyasi case hardly made news outside Bengal, but this sadhu was to become the talk of the nation. They called him Swami Saradananda or Shaulmari sadhu, the sadhu from Shaulmari pocket in Falakata. He had a full-fledged ashram of his own, the Shaulmari ashram.

No one was admitted without permission from the ashram authorities which had to be obtained beforehand through a rigorous application process. Nobody was allowed to bring a camera, but everyone who went in was photographed. Nobody was allowed to enter the sadhu’s private rooms, not even the administrator of the ashram. Those who saw Shaulmari sadhu said he smoked expensive cigarettes and conversed in Bengali and English. None of it raised eyebrows as did the claim that he was Bose in disguise.

Also read: Pakistan exploited India’s Article 370 fully. Fuelled Kashmiri Muslim resentment

Quite naturally, it was not too long before the state police and intelligence apparatus descended at the locality in hordes. On 6 September 1961, the deputy commissioner of police, Cooch Behar, informed the state’s home secretary, ‘Careful watch has been kept by the police on the ashram, but so far it has not been possible for the police to locate and identify the sadhu.’

Things got curiouser when a key member of the ashram’s administration, Haripada Basu, sent telegrams to both Prime Minister Nehru and Chief Minister Roy linking Shaulmari sadhu to Bose. We found this reported in a dispatch from the district intelligence officer of Jalpaiguri on 11 February 1962. Haripada was promptly expelled from the ashram and a denial was issued. ‘It is hereby emphatically announced that the founder of the Shaulmari Ashram is not Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose,’ read a declaration by Ranjan Das, secretary of the ashram.

In March, Das’s father confided to a relative who worked in the police department that although he hadn’t met Saradananda, he believed that the monk was Bose. In February 1962, ‘Major’ Satya Bhushan Gupta announced that after meeting Saradananda he didn’t have the slightest doubt that the sadhu was indeed Bose. Gupta’s claim generated a lot of interest, given that he was a leader of the highly admired Bengal Volunteers, the erstwhile revolutionary group in Bengal owing fanatical allegiance to Bose.

Gope Gur-Bux, the ashram’s assistant administrator, and in-charge of public relations, stepped in to issue a categorical denial. On 27 February 1962, he declared that ‘the Founder of the Ashram, Shrimat Saradanandji is neither Netaji Shri Subhash Chandra Bose nor has he any relationship with Netaji or his family.’ A couple days later, he again issued a statement directed at Gupta and certain newspaper editors that ‘“Mystery” may be in the minds of such people (but not within the bounds of the ashram).’

In a turnaround, Haripada Basu declared in a public meeting at Falakata in April 1962 that he was wrong. Standing next to him was Niharendu Dutt-Mazumdar, a barrister who was once Bose’s close political aide and later a minister under B.C. Roy for some time. He would go on to represent the Bose family before the Khosla Commission.

Dutt-Mazumdar said that he was providing legal advice to the ashram administration. Siddhartha Shankar Ray, another barrister who was to later become the state’s chief minister, had also appeared in the courts on behalf of the ashram for some time. Dutt-Mazumdar met Saradananda several times and was emphatic that he was not Bose.

Meanwhile, cops were going about it scientifically. They obtained a sample of Saradananda’s handwriting and a CID expert cross-checked it against Bose’s handwriting. Though the samples were not sufficient to draw a conclusive inference, the expert did not see a match.

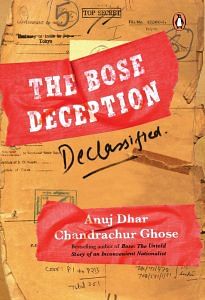

This excerpt from ‘The Bose Deception: Declassified’ by Anuj Dhar and Chandrachur Ghose has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.