In the year 2000, I would stand against the railing on the tiny terrace garden in Jayanagar, looking out over the coconut palms and houses of South Bangalore. The sky was often cloudy, and a damp wind would make the palm fronds sway and bend. At a particular time of year there would be flaming orange flowers on another kind of tree. I never knew for a fact what the tree was called—Rain Tree? Flame Tree? Day after day, the vista from my terrace changed only to the extent that the sky changed.

I wrote up a “Bangalore Diary” and sent it to a magazine editor, via a friend. The editor told the friend that his magazine “tended to go for a more prominent byline”. Like everything I tried to do in Bangalore for about ten years between 1995 and 2005, my attempts at reportage also ended in disappointment. Bangalore is one of the fastest growing cities in India and the world, its coconut palms and fire-flowered trees cut down each day to make way for new roads, high-rises and shopping malls, but for me it was and will always be a city of failure.

There are several reasons for this, only some of which may be shared here. One was the sudden demise, in the summer of ’98, of my teacher, D.R. Nagaraj (1944-1998).

D.R. closed many doors behind him as he left. He was thinking about Gandhi and Ambedkar in a way that it took me a decade after his death to be able to reconstruct and appreciate. He was on to something radically unassimilable that lurks at the heart of Indian modernity—a tradition of ethical thinking in Indian political discourse that does not submit to the hegemony of the modern West.

D.R. was suspicious of both Ambedkar’s radicalism and Gandhi’s conservatism. He saw these two figures as inextricably coupled, complimenting, contradicting and completing one another. Political modernity in India is the child of this coupling of Gandhi and Ambedkar which means that caste and religion are in its DNA. The emergence of the modern from pre-modernity is the central problem in Indian history. It took me time to realise that in his precocious way, D.R. had figured out exactly this.

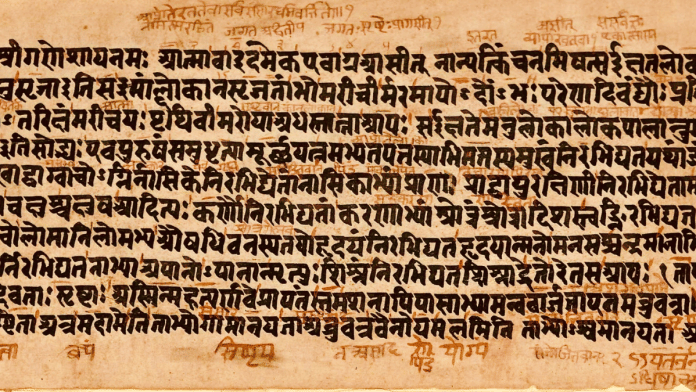

But apart from D.R.’s absence, which was a given when I first arrived in Bangalore to begin my research in late 1999, what got me down was my mission there: reading Sanskrit texts. This is not as counter-intuitive a proposition as it might sound. The high-tech boom in Bangalore is no older than the beginning of the new millennium; its traditions of Sanskrit pedagogy are considerably older. Bangalore may be India’s Silicon Valley today, from the mid-90s into the early 21st century, but it has participated in earlier political and cultural formations falling within the kingdom of Mysore until 1956. It has the educational and religious institutions of a number of brahmin and Lingayat orders—Madhva, Sri Vaishnava and Shaiva, among others. Brahmin communities settled in Bangalore speak Kannada, Tamil, Telugu, Tulu, Marathi, Malayalam—all the major languages of the Deccan and the peninsula, indicating the regional origins of their speakers. As a student wishing to read a small number of Sanskrit texts I didn’t expect any difficulty in finding a suitable teacher.

In hindsight, what I remember most about studying Sanskrit in Bangalore, is crying. Crying in the rickety old Tata vehicle that I drove several times a week from the flat in Jayanagar to the Poornaprajna Vidyapeetha; crying in the bathroom with the shower running to drown out the sound; crying in Basavanagudi, in Sri Nagar, in Chamarajpet, unable to stem the tears for months, until I fled in 2001 to Pune. When I stood in the wet, cold air on my terrace my own grief seemed unfathomable. The flowers blazed orange against the deep green foliage and the cloud-darkened sky.

‘Bangalore has the best weather of any city in India!’ exclaimed my family members from distant Delhi. They would have liked to visit but I seldom called them, and would rather have gone to see them than invited them over. In those days one still had to go to a phone-booth to make long-distance calls. There was one on my street but I avoided going there. I was worried my parents would know from my voice that I had been crying. My eyes were always puffy, my head ached, my heart was heavy. I tried to take Kannada lessons from a series of tutors, one worse than the other, so I could begin to read something of the indecipherable environment with its seasons all wrong, its unfamiliar script, and its pain. “To have suffered,” writes my advisor Sheldon Pollock in his commentary on one of the books of the Ramayana, “was ineluctable.”

Sometimes I took D.R.’s children, his young daughter and little son, for a ride in my decrepit car or out for a meal in one of the South Indian restaurants in south Bangalore. I met friends at Koshy’s, yet to be renovated in those days. There was Manu Chakravarthy, a professor of English who had interviewed Edward Said; George Kutty who ran a journal of film studies; Murari Ballal, an intellectual who lived in Udupi, in coastal Karnataka; Sathya Prakash Varanashi, an architect who built using indigenous techniques; and so many others—novelists, painters, academics, journalists, activists, and dancers…

I went to the homes of Ramachandra Guha and U.R. Ananthamurthy and got to know their families. Some days were brightened by conversations in these charmed circles. Other days were taken up driving to the dusty library at the Institute for Social and Economic Change; or attending seminars at the National Institute for Advanced Studies; or listening to lectures by visiting scholars at the Centre for the Study of Culture and Society (which shut down a few years later); or at the Alternative Law Forum (which was just starting up). I knew a few of the scientists at the National Centre for Biological Sciences and the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research. Bangalore was full of clever people and institutions, both old and new.

Now and then, friends from the University of Chicago or other foreign universities would come to town for their own research, and stay in the flat for a few days before travelling to more remote locations. A Dutch photographer, an American anthropologist, scientists, coders, investors, venture capitalists, all types passed through town, visiting for a bit and sometimes staying on for months or years. But in returning from this cosmopolitan company to my studies with Sanskrit pandits, I would again lose heart and feel my spirits flag. Now I know something that I didn’t know then—to have suffered was ineluctable.

In his melancholic memoir, The Last Brahmin: Life and Reflections of a Modern-day Sanskrit Pandit, Rani Siva Sankara Sarma writes that brahmins are obsessed with death. I have been rolling this ball around in my head.

Is this true? My father was a brahmin. I know he was obsessed with death but that is neither here nor there. Was it the stench of death that got me, in the Vidyapeetha, in the Sri Chamarajendra Sanskrit College, in the various mathas and private homes and manuscript libraries that I visited as a graduate student, for all those years, lost in a fog of sadness?

I wrote a short piece titled, “The Archivist” and showed it to Ram Guha. He encouraged me to write, to think about myself more as a writer than an academic, but the story irritated him. It was about an old librarian in Pune, the keeper of a Sanskrit archive, on the last day of his life. A young woman with a large shambling old car, rather like my own at the time, gives him a ride to what will eventually be discovered as the site of his death. “This is too maudlin for my taste,” Ram said. I was crushed. But unbeknownst to myself or my disapproving reader, perhaps I had accidentally accessed within my unconscious mind that feeling for death that is undying through the generations.

There are times when I consider myself a brahmin, although strictly speaking, half-castes and women don’t count. Yet I am so much my father’s only child and so mired in his sombre and agonised world, so hardwired with his pathologies, that I could not be anything else. As a social scientist I am deeply opposed to identity politics, but I recognise that some aspects of identity are inescapable, neither constituted nor imputed nor ascribed but innate, self same, who one is. Sarma describes his solitary monologues addressed to no one, he describes mental illness in his family—his father’s insomnia, his own tendency to have conversations with himself aloud, the depression and dementia of his sister. These conditions are not separate from the life of his immediate and extended family—its ancient provenance, its dying traditions, its inwardness, an intellectually rigorous and emotionally dysfunctional bubble which will burst any day or carry on into eternity, it’s hard to say which.

Sarma depicts a hermetically sealed life-world that finds modernity unheimlich. Into this world I would daily crash, with my big car and my short hair, wearing a sari that no matter how ‘traditional’ simply did not endow me with the requisite body-language of female subservience. I turned up again and again, with my conspicuously brahmin surname, redolent of Krishna’s discourse to Arjuna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, Vedic sacrificial altars, and queens in remote antiquity copulating with wild horses. And in this world that should have felt like home, I could not breathe. I choked and I wept, failing utterly to make headway. Nowadays we have a term for how I felt: ‘imposter syndrome’.

Had D.R. stayed alive he would have counselled humour. His friend, the brahmin Murari Ballal, who also died in a freak road accident in 2004, once invited me to witness a possession ritual in Ambalpadi, Udupi, where he lived. But he was careful to take along an umbrella and to warn me that we could stay no longer than 10 or 20 minutes, as though he understood that we were moderns who have no stomach for extended doses of brahmin—or non-brahmin— practices. After a visit to the Shri Krishna Temple in Udupi he always took one to Diana Cafe nearby, to touch base with the profane world in which one really belonged. Did I cry because I saw that the brahmin way of life was about to vanish? Or did I cry because it had outlived itself and had no business inflicting its burdensome anachronism on modern India?

The pandits I read with were gentle—harmless, you might say—and in their own way, kind. But it made them uncomfortable that I was a woman. Since there was no changing this fact they made room for it, to whatever extent they were able. It was really the material I wanted to read, legal digests about Shudra Dharma, from the 16th and 17th centuries, that irked them most. Here was brahmin orthodoxy spelt out in no uncertain terms. Did the contempt for low caste people detailed in these texts offend my pandits? Or were they hostile to what they imagined was my rejection of the values articulated therein? Did they know that the spell had been broken, forever, by the coming of egalitarian citizenship, and that they could not translate the pre-modern into any terms that might even be comprehensible, leave aside acceptable, to someone like me?

“If a dog is sleeping,” said the only pandit I actually liked, “do we prod it awake with a stick? Leave these texts alone, let them be, they are of a time long gone.” But it was too late. Shudra Dharma snarled at us from the table, snapped at our bare feet, and filled the dingy room with fear. The only historians I know who understand the fear one can feel from the past, from its irrationality, its violence, its immutability, are those who study the Holocaust. In its own way, Indian pre-modernity, too, can be terrifying, its assumptions unspeakable and indefensible.

This excerpt from ‘Place’ by Ananya Vajpeyi has been published with permission from Women Unlimited.

This excerpt from ‘Place’ by Ananya Vajpeyi has been published with permission from Women Unlimited.

If only more of us felt similarly…!

Another self-indulgent academic piece masquerading as scholarly work. Ananya Vajpeyi presents a narrative that’s more about her personal emotional breakdown than any serious research into Sanskrit texts.

Let’s be clear:

She admits she couldn’t understand the language

Her mentors were patient and willing to explain

Yet she turns her academic struggle into a melodramatic tale of oppression

The real comedy is her claiming to “confront” historical texts when she can barely read them. Her crying fits seem less about scholarly insight and more about personal inadequacy. She juxtaposes complex historical legal texts with her own inability to comprehend them, creating a narrative that’s more about her feelings than actual research.

The references to her brahmin background, her mentors, and the scholarly environment in Bangalore read like a desperate attempt to inflate her academic credentials. Her constant emotional outbursts – “I cried and cried” – reveal nothing except her own academic incompetence.

This isn’t scholarship. It’s a self-absorbed memoir of academic failure dressed up in intellectual pretension. Instead of doing the hard work of truly understanding the texts, she’s manufactured a narrative of victimhood and cultural critique.

If this is the state of contemporary academic writing, no wonder serious scholarship is in decline.