In 1932, Gangubai was carrying her second child. In the same year Ambabai also fell seriously ill. She was diagnosed with stomach ulcers and had to undergo surgery. However, the doctors told her that it was not an emergency, and she could wait for six months before undergoing the surgery. Ambabai wouldn’t listen. She had her own plans. “After six months? It will not be possible. That’s the time Gangu will have her baby, and I have to be at her service. Else, who will nurse the mother and the baby?” She was worried also that it might disrupt Gangubai’s music lessons that were just about moving towards stability. Ambabai underwent the surgery almost immediately, but unfortunately there was a rupture in the stitches made, which led to excessive bleeding—Ambabai didn’t survive. Gangubai was shattered. “Imagine my life without my mother … she was the breath of my life … I stopped singing.”

Chikurao Nadiger came rushing from Ranebennur for the last rites. He was heartbroken. Overcome by the grief of Ambabai’s death, the man lost interest in everything. He did not live for long after that, and was gone in a year. Without much emphasis on meaning or intent, Gangubai had narrated the following episode: “A few months ahead of my mother’s death, an astrologer had come to our doorstep. He predicted that my father would lose his wife. On hearing this, my mother was grief-stricken. She worried endlessly about how my father would manage with his wife gone. She often expressed her anxiety to me. But it was my mother who died.”

Just before Ambabai’s death, HMV had come to the south, exploring voices that could be recorded. They had asked Gangubai to sing for them and had even fixed a future date. Ambabai’s death had, however, left her in no state of mind to render even a single note. She flatly refused and asked for her contract to be cancelled. Dattopant and Ramanna stood by her like solid pillars. They gently coaxed her to sing, and kept consoling her. In fact, every morning Dattopant would arrive at their house. The first thing he would do was to tune the tanpura, and then would keep strumming it. He hoped that the resonating drone of the tanpura would fill both house and heart, and Gangu would get back to her music. It was not easy. This went on for months, and Dattopant did not give up. Ramanna, too, had to join Dattopant. As he ran his fingers on the tanpura, Ramanna would keep the rhythm. Before Dattopant’s silent persistence, Gangu’s obduracy seemed frail. “I eventually realized that music was the only way to keep my mother in my thoughts constantly. She always dreamt of making me a great musician. And Dattopant was always around to share her dream. I gave up mourning, picked up my tanpura and started practising.”

Also read: Why Ambujammal hid her pearl necklace when Gandhi came to her house

Life had to go on. There were practical, everyday questions that had to be addressed. What would help put food on their plates if she stopped singing? She was a school dropout, and music was her only route to survival. There were occasional requests for her to sing at small gatherings, family functions or festivals. There used to be a Saturday baithak at their home as long as Ambabai lived. There was a regular, small audience for the baithak. Even during the period of Gangubai’s mourning, they came, sat for a while, and left some money for her. In her later years, she would recall all these gestures with immense gratitude. As soon as she realized that she had to resume singing, she shouldered the Saturday baithaks. With the little money she earned, the family pulled along with great difficulty.

“During the first death anniversary, family members are supposed to give away a sari to a sumangali (a lady whose husband is alive). My mother’s death anniversary approached, and my condition was appalling. I had no money, not even a few rupees to buy an ordinary sari. Dattopant knew. He did not even ask. On that day, he placed a sari in my hands. I was so moved by this gesture, I could not stop crying. His affection was so selfless. You think I would have been all this without the unconditional love I received from people like Dattopant? He was always there for me …” Gangubai would say, sobbing uncontrollably.

It was time for her to go to Bombay for her recording with HMV. “My mother had so many dreams for this day. It was my very first recording and she was not a part of it.” She left for Bombay with Dattopant and Ramanna. She had no money to buy herself a new sari. She gave her everyday saris an extra-good wash, pressed them under a pillow and took them along. On their way they stopped at Pune, and paid a brief visit to her guru, Sawai Gandharva. Gangubai presented before him all the eleven songs that she was to sing at the recording. Sawai Gandharva listened carefully, and gave them the necessary polish.

Both in Pune and Bombay, people made rude remarks about her clothes. Gangubai had no illusions about her looks or clothes. With music being the mission of her life, she was in no position to take these comments seriously. She wasn’t even the kind who would return those taunts. “I would just laugh and keep quiet.”

Gangubai enjoyed her Bombay trip thoroughly. Along with other artistes from various parts of the country, she was stationed at a hotel in Girgaon. Each of them had to present a set of eleven songs, and it had to be an eclectic selection. Gangubai presented her compositions. There were pieces in ragas Natakuranji and Madhyamavati, taught to her by her mother, alongwith Marathi natyasangeet, also composed by her mother. She sang Miyan ki Malhar along with the other pieces. “We were not paid for this. However, they took care of our travel, accommodation and food, and even took us around Bombay. It was the beginning of many things for me.”

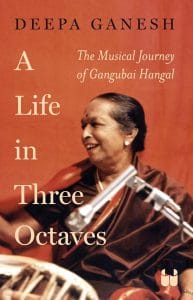

This excerpt from Deepa Ganesh’s book, ‘A Life in Three Octaves: The Musical Journey of Gangubai Hangal’, has been published with permission from Westland Books.

This excerpt from Deepa Ganesh’s book, ‘A Life in Three Octaves: The Musical Journey of Gangubai Hangal’, has been published with permission from Westland Books.