When it comes to India, there are four European powers that are worth a mention and unfortunately, their invasions were marred by brutal genocides.

If not for the early invasions by the Portuguese and the Dutch, a market for Indian goods would not have been created and the English and French might have never known the richness of produce of the land of Hindustan. But why did it come down to a tug of war between the French and British only?

First came the Portuguese. They dominated all the sea routes between the Indian Ocean and Europe via the Cape of Good Hope for most of the sixteenth century, thanks to the establishment of this route by the successful journey of Vasco da Gama from Portugal. Blessed with superior fire power to intimidate rulers and traders in Asia, the Malabar coast was their initial domain of violent conquest as well as centre of trade. They bombarded and destroyed Calicut to show how dangerous they were. At one point, other than Hormuz at the entrance of the Persian Gulf, they had factories-cum-naval bases established along the west coast of Hindustan, Macau in China, Timor in Indonesia, Malacca close to Singapore and Colombo in Sri Lanka. They started calling their territories Estado da India, with Goa as their headquarters.

The Portuguese were so powerful, that other ships had to carry a card or passport issued by Estado da India, if they wanted to sail these territories. They also got involved in local political disputes and embedded themselves in Indian society. It was only towards the end of the sixteenth century that the Portuguese monopoly on the Cape of Good Hope began to be challenged by other European traders. It was the Dutch that came knocking first.

Dutch colonialism was fronted by a joint stock company from the Netherlands called VOC. They started by trying to take over some of the Portuguese locations. Their main interest was in Indonesia, but when they found that the prices of spices in Bantam were higher than they expected, they bombed the city and killed the indigenous people brutally. Evidently, nutmeg, mace and pepper were seen to be more precious than human lives. Similarly, the VOC’s conquest of Banda Islands involved a genocide. The directors in Amsterdam had actually instructed officials to repopulate the islands. The Dutch were so strong at the time that when a few servants of the newly founded EIC tried to gain a foothold in the early seventeenth century, they were brutally wiped out. Similarly, the VOC made Java the base of its operations.

Also read: Who has the rights over Nepal’s historic Taleju Bhawani necklace?

India became crucial to the Dutch when they discovered that cotton textiles from Gujarat and the Coromandel were in demand in South Asian markets. While it was easy to get access to Pulicat and Nagapattinam by dislodging the Portuguese, the real battle was for Surat, which was a major supplier of textiles, but also a premier port of the Mughal Empire.

The Mughals encouraged the rivalry between the Portuguese and English because it meant more competitive trade for Surat’s merchandise. A market for Indian textiles was being developed in Europe. For example, the Dutch unlocked the potential of Indian trade by finding a market for Bengal raw silk in Japan.

And so it was that when the EIC wanted to put its roots down in the seventeenth century, the Dutch stranglehold over South-east Asian spices was tough to break. The good thing for them was that they had set up a textile factory in Surat in 1613, even before the Dutch, and this, along with sourcing tea from China and indigo from India, was a good start to their trade. Later, a United East India Company was formed, which enabled more traders and financiers to participate in the lucrative trade in Asian merchandise. The first actual settlement of the British began after Andrew Cogan, an agent of the EIC, reached Madraspatnam on 20 February 1640. The British built Fort St George, which led to the creation of what we will refer to hereon as Madras.

The seven islands of Bom Bahia, which were in Portuguese possession till the mid-seventeenth century, were transferred to the English crown by a marital dowry in 1665. With this, Bombay became the western headquarters of the EIC, and they had some presence in Bengal as well. The EIC solidified its trading position step by step. It is to their credit that in the first decade of the eighteenth century, the English organized themselves better towards commercial profitability.

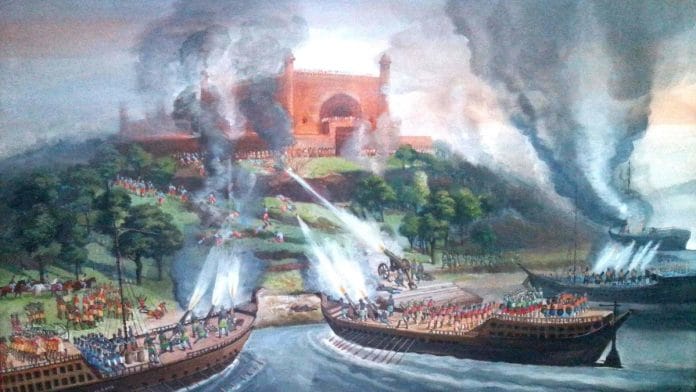

However, they faltered when they decided to show the Mughals their military prowess; the decision to involve their navy and attack the Mughals backfired badly. The Cambridge History of India explains the British war with the Mughals, also called the Anglo-Mughal war of 1686–1690:

The seizure of some Mughal vessels brought about a rupture towards the end of 1688, with the consequence that the factors (sic) at Surat were imprisoned. Child [John Child of the EIC) in retaliation, captured a number of richly freighted ships. Thereupon ensued a siege of Bombay by the Mughal forces until in 1690, the English put an end to the war by a humiliating submission involving the payment of a considerable sum. Child, whose dismissal was one of the conditions of peace, died just as the negotiations were reaching a conclusion.

At this time, the powerful Mughals, led by Aurangzeb, would let nothing untoward happen in their territory. While it took some time for the EIC to recover from the setback of the war against the Mughals, this is probably one of the reasons why the British chose to train their attention first in the south of India, where the Mughals were practically non-existent.

But Aurangzeb’s death changed everything.

So much so, that a decade later, in 1716, on New Year’s Eve, Farrukh Siyar, the weak Mughal Emperor, was bullied into issuing a farman, granting the British EIC Company full trading rights. The wolfish EIC had finally managed to make political headway into Mughal India, through a direct relationship with the Mughal Emperor.

But by now another European competitor had emerged on the scene: the French East India Company. During the period between the 1720s and the 1750s, the French and the English were locked in a fierce battle to dominate the colonial enterprise of the Indian subcontinent, even as the Dutch company ceased to be a significant player.

Under Pierre Benoit Dumas, the Governor of the Indian territories of the French East India Company from 1735 to 1741, the French started intervening in local conflicts to extend the scope of their influence.

This excerpt from ‘Murarirao Ghorpade: The Accidental Catalyst Behind Robert Clive’s March Over India’ by Reeta Ramamurthy Gupta and Indrajeet Ghorpade has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘Murarirao Ghorpade: The Accidental Catalyst Behind Robert Clive’s March Over India’ by Reeta Ramamurthy Gupta and Indrajeet Ghorpade has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.